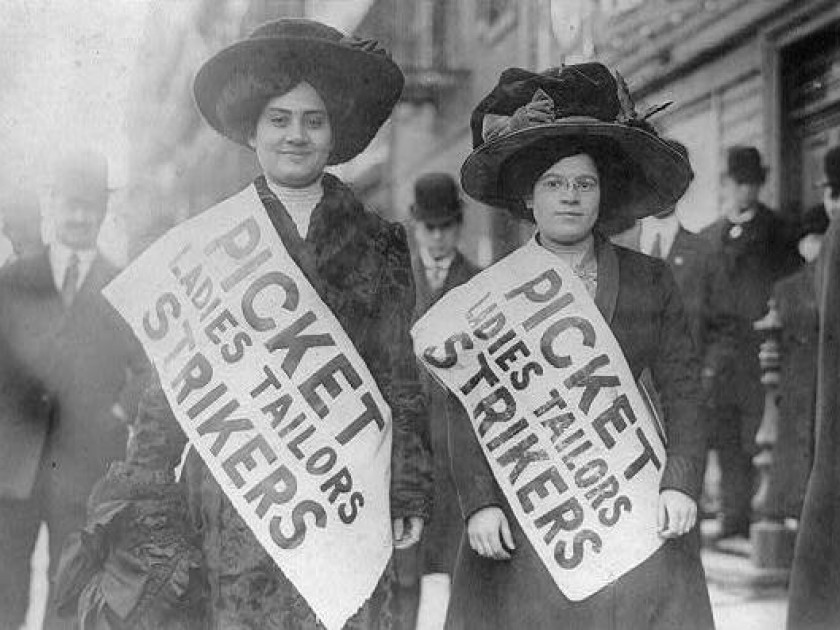

Two women strikers picketing during the New York Shirtwaist Strike of 1909, led by Clara Lemlich and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, supported by the National Women’s Trade Union League of America

Clara Lemlich was born on March 28, 1886, in western Ukraine, about fifteen miles from Lviv, in a shtetl named Gorodok where nearly one third of the residents were Jewish. She was raised in a patriarchal, Yiddish-speaking household, which meant that as a young girl, she was denied the education her brothers received. Barred from the village’s sole public school because she was Jewish, she was forbidden by her parents to learn Russian. Clara defied them. Older acquaintances tutored her in the language and loaned her books by Tolstoy, Gorky, and Turgenev. A neighbor exposed her to anti-czarist screeds and Socialism. She earned money by sewing buttonholes and writing letters for illiterate villagers to relatives who had emigrated to America.

In 1903, when Clara was seventeen, the bloody Kishinev pogroms in Moldova finally provoked her parents to escape with her and her four brothers. They arrived in December 1904 on the American Line’s SS New York. According to the manifest, her father, Schimschan (Simon) Lumback, described his occupation as a bookbinder. He had been living in London, he said, had thirty dollars in his pocket, was neither a polygamist nor an anarchist, and was joining a cousin who lived on Stanton Street on the Lower East Side. Clara, listed as Cheise, identified herself to immigration authorities as a nineteen-year-old tailoress.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, more than half of the clothes manufactured in the United States were made in New York City, with most women’s wear produced by immigrant girls who confronted gender inequality, sexual harassment, squalid and unsafe working conditions, low wages, and long hours. In a job market defined by volatile turnover and seasonal demand, Clara was hired within a few weeks after she arrived in New York in 1904. She rapidly advanced to a handsome sixteen- dollar-a-week salary as a draper, creating the patterns for mass production of specific blouse and dress designs by meticulously placing fabric over a mannequin. But, she later recalled, “the hissing of the machines, the yelling of the foreman made life unbearable” — even worse, she told the New York Evening Journal, “than I would imagine slaves were in the South.” She and her colleagues worked sixty-five, sometimes seventy-five-hour weeks. They often had to supply their own needles and thread.

Determined to improve her lot, Clara began by enrolling in the Educational League on Madison Street to learn English. She studied Marxist theory at the Socialist Party’s Rand School of Social Science, and educated herself at the East Broadway branch of the New York Public Library.

“We’re human, all of us girls, and we’re young,” Lemlich told readers of Good Housekeeping magazine. “We like new hats as well as any other young women. Why shouldn’t we? And if one of us gets a new one, even if it hasn’t cost more than 50 cents, that means that we have gone for weeks on two-cent lunches — dry cakes and nothing else.” A beautiful building on Fifth Avenue was a Potemkin facade, she said, for a factory where three hundred workers competed for one sink and two toilets, where the office clock was draped to prevent them from even glancing up to check the hour and cheat the bosses on overtime. The girls walked out “to prevent themselves from being starved out,” she said. “The manufacturer has a vote; the bosses have votes; the foremen have votes; the inspectors have votes. The working girl has no vote.”

Jews — including housewives, who already had a history of protest in rent strikes and kosher meat boycotts — and Italians, leery of organized labor in the beginning, edged warily into blue-collar alliances. These coalitions would spur the rise of politicians like future congressman and mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who at the time was finishing law school at New York University while working as an interpreter on Ellis Island. Among the first hundred immigrant girls Lemlich canvassed, only five agreed to join the union. “What did I know about trade unionism?” she said later of her fortitude. “Audacity — that was all I had — audacity.” Her swagger, her refusal to be relegated to a cog, was what made her stand up to the bosses: “Girls, to them,” she said, “are part of the machines they are manning.”

Rose Schneiderman and Pauline Newman, who would later be universally celebrated as labor heroines, served as Lemlich’s mentors. When she began working at Leiserson’s, Annelise Orleck wrote in Common Sense and a Little Fire (2017), Lemlich brazenly “marched uninvited into a strike meeting that had been called by the shop’s older male elite — the skilled cutters and drapers — warning them that they would lose if they attempted to strike without organizing the shop’s unskilled women.”

On August 12, 1909, five self-styled detectives hired by Rosen Brothers to protect Italian girls unwilling to jeopardize their jobs for union solidarity physically beat Lemlich and several other pickets during an altercation that left her hospitalized. She hid her broken ribs and bruises from her parents. The “detectives” — a prizefighter and several ex-convicts — were miraculously arrested, but a month later, even as Lemlich remained hospitalized, they were released from jail. The strikers were fined ten dollars each for disorderly conduct. But then wealthy women like Anne Morgan, J.P.’s maverick daughter, and Alva Belmont, whose father-in-law, August Belmont, was investment banker to the Rothschilds, provided more than money and moral support. They put their bodies on the line. The arrests of middle- and upper-class picketers made the manufacturers squirm.

Having been arrested seventeen times while organizing or picketing, Lemlich, barely five feet tall, had no compunctions about challenging her union’s male leadership. Asked later how she managed to organize twenty thousand largely uneducated workers, Lemlich replied: “Well, to be honest, I didn’t really organize them; I really just motivated them.” She went on to recount how she felt that night at Cooper Union, listening to the speeches: “They just made me so mad because they talked in such general terms about the need for solidarity and preparedness and all that.” Instead, “I demanded action … I was just saying what all the workers were thinking, but they were just too afraid to say.”

Lemlich remained unapologetic and unreconstructed, protesting a broad range of what struck her as injustices.

Lemlich’s role didn’t end with her words at Cooper Union. “A committee of men is handling the strike, but Clara Lemlich, a pretty East Sider of 19 years, is the Joan of Arc who is recognized as the sentimental leader,” the Evening Republican of Meadville, Pennsyvania, reported. “She went about everywhere encouraging her companions and kept enthusiasm at high pitch.” A Jewish weekly in Chicago, the Reform Advocate, declared: “The soul of this young woman’s revolution is Clara Lemlich, a spirit of fire and tears, devoid of egotism, unable to tolerate the thought of human suffering.” On the picket lines, the New York Sun reported, “The girls, headed by teenage Clara Lemlich, described by union organizers as a ‘pint of trouble for the bosses,’ began singing Italian and Russian working-class songs as they paced in twos before the factory door.”

Many of the smaller shops met most of the union’s demands early on, but the larger factories held out longer, defying the pickets by hiring scabs and even shifting production out-of-town. Wage increases were negotiable. So was reducing the workweek from as much as seventy-five hours in high season to fifty-two. What Triangle and the other biggest owners absolutely refused to budge on was recognizing the union and negotiating an industrywide collective bargaining agreement. As the walkout dragged on, the strikers’ stamina was sorely tested, as Gompers had predicted. But as pickets paced in temperatures that averaged below freezing, a number of them suffered from malnutrition, and some seven hundred were arrested, public opinion began to shift. Even the Times was edging toward the view that responsible unionism, leading to constructive partnerships with management — what was being described under the broad umbrella of industrial democracy — was a necessary evil to fend off more radical and even revolutionary alternatives.

When the strike finally ended in mid-February 1910, after nearly three months, the union had won the battle, if not the war. Of the 353 member firms of the Associated Waist and Dress Manufacturers, representing the factory owners, 339 signed contracts that provided for a fifty-two-hour week, four paid holidays annually, provision of tools without fee, and job safeguards for union members. Within a few years, the so-called needle trades became a model of industrial unionism in America.

These labor victories must have gratified Clara Lemlich, but they didn’t help her much professionally. Because her father (who, like his wife, had arrived from Russia illiterate) had difficulty keeping a full-time job, she often had to be the family’s main breadwinner. She applied for work under aliases but was hounded out of the garment business.

On March 25, 1911, thirteen months after the shirtwaist workers’ strike ended, a fire in the Triangle plant on Washington Place killed 146 workers, mostly young immigrant girls working late on a Saturday and unable to escape because exits were barred to prevent theft. The fire galvanized garment workers, progressives, labor organizers, and Democratic politicians into a muscular coalition that would shape social policy for decades. “If it had been a union shop,” Lemlich said, “there would not have been any locked doors, and the girls would have been on the street almost an hour before the fire started.”

Consumer advocate Frances Perkins was having tea at the Washington Square town house of Margaret Norris, a descendant of Alexander Hamilton, when she was stirred by steady wail of sirens and raced to the scene. At former president Theodore Roosevelt’s recommendation, Perkins was named to head a committee on safety, which led to the appointment of a commission to investigate the factory. Its staff of inspectors — apparently at Perkins’s suggestion — included Clara Lemlich. (Workplace owners were outraged. “It would seem,” said one, “that in view of what Miss Lemlich says she has suffered at the hands of manufacturers she would be rather a prejudiced person to entrust to factory inspections.”) In The Triangle Fire, the Protocols of Peace, and Industrial Democracy in Progressive Era New York (2005), Richard A. Greenwald wrote that the commission “not only transformed working conditions in New York, it invented urban liberalism and forged the first working alliance between middle-class experts and reformers and machine politicians.”

In 1911, Lemlich would also help found the Wage-Earners Suffrage League with Leonora O’Reilly and Rose Schneiderman. She married Joseph Shavelson, a printers’ union activist, in 1913 (becoming a U.S. citizen as a result), moved in with his sister in Brooklyn, and devoted much of her time to raising three children. (Her two daughters both became social crusaders. Her son, Irving Charles Shavelson, a machinist in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, abbreviated his surname to Velson. He was later identified as a Soviet military intelligence agent in the Panama Canal Zone and who in New York collaborated with Bernard Schuster, the American Communist Party official who recruited Julius Rosenberg to steal American military secrets.)

By the mid-1920s, Lemlich was organizing boycotts of kosher butchers to protest high prices, leading rent strikes, and challenging evictions. Around 1926, she joined the Communist Party; she was the party’s nominee for alderman in 1933 and for the state assembly from Brooklyn in 1936. She helped establish the nationwide United Council of Working Class Women, and during the Depression she mobilized a boycott that managed to shut down an estimated 4,500 butcher shops in New York City in protest against meat shortages and price gouging.

In 1944, after her husband got sick (he died in 1951), Lemlich returned to work in the garment industry. She retired three years later, beginning a protracted struggle with the ILGWU, which denied her a pension because she lacked fifteen years of consecutive service, though its venerable president David Dubinsky eventually intervened and awarded her a modest stipend.

Lemlich remained unapologetic and unreconstructed, protesting a broad range of what struck her as injustices. In 1960 she married Abe Goldman, an old acquaintance from the labor movement. When he died in 1967, she moved into the Jewish Home for the Aged in Los Angeles. (Her daughter Martha Schaffer lived in California, where she, too, was an advocate for social justice; her other daughter, Rita Margules, was in New York.) Even in her eighties, she successfully lobbied the administrators of the retirement home to honor the United Farm Workers boycott of nonunion grapes and lettuce, and even helped the orderlies there to form a union.

Excerpted from The New Yorkers: 31 Remarkable People, 400 Years, and the Untold Biography of the World’s Greatest City. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2022 by Sam Roberts

Sam Roberts, a 50-year veteran of New York journalism, is an obituaries reporter and formerly the Urban Affairs correspondent at the New York Times. He hosts the New York Times “Close Up,” which he inaugurated in 1992, and the podcasts “Only in New York,” anthologized in a book of the same name, and “The Caucus.” He is the author of A History of New York in 27 Buildings, A History of New York in 101 Objects, and Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America, among others. He has written for the New York Times Magazine, the New Republic, New York, Vanity Fair, and Foreign Affairs. A history adviser to Federal Hall, he lives in New York with his wife and two sons.