Learn more about Site: Yizkor

Mrs. Elia Rose, née Braca, died in her apartment sometime in the winter of 2015. She was 98 or 99, a radio star of the 1930s. Her stage name was Lynne Howard.

I knew her as a frail figure who walked the hallways for exercise.

One time we found her sitting by the window as smoke billowed from her apartment. She said, “I turned the oven on for heat, as you do, and my nurse had left a chicken in there.” It was the middle of July.

They came and cleaned out her apartment. First her children, then the neighbors, then the professionals. This is what happens with death. People come and touch your things. They keep them or throw them in the fire. Why have things at all? Is your spirit held in these objects? When they are burned, buried, or crushed is your spirit released?

Who honors the spaces left by the dead? Mrs. Rose occupied a space. She filled it with her history and the history of her ancestors and the canvasses of her dead husband Herman. Elia Braca Rose, a Jewess who adopted a gentile name, as you do.

— Maya Ciarrocchi

Shotgun house

Tall old oak

Grandiose hallway

Royal carpet runner

Glass/brass ornate doorknobs

Baby grand piano

Musty basement

Ceramic pigs

Porcelain dolls

Mothballs in cardboard boxes

Dim green lights

Dusty pool table

Five thousand piece puzzle of a black & white tiger in space –

There were pieces missing

Steep staircase to the second floor bedroom to the left and right

To the left my aunt’s

To the right was my grandma and grandpa’s

I used to watch cartoons with grandpa in the living room

He died on my fourth birthday

Kitchen cabinets filled with black olives

My grandmother’s name was Olive

My last memory of the home was watching my mother and aunt

Fighting over who got what

An empire of boxes

— Scott Wheet

My mother purchased 35 Pine Court in the mid-1960s, about ’64.

It was a one-story bungalow. Two bedrooms, a bathroom, kitchen on the back. Not quite enough windows on the front and a little brick fireplace in the center that always ran counter to purpose and made the house colder in the winter with drafts.

The house had been built on spec, as part of a little grouping of similar bungalows around Sanford Lake. All of this was in Michigan, a state with over 10,000 lakes, and yet Sanford Lake was made by damming two rivers and flooding a slight valley to build small houses so that a single woman, with hopes of marrying soon, could buy a home of her own after all those years seeing the world through Appalachian Depression-era eyes. The summer after my mother died, the house was put on a trailer and carted off. The crawlspace was filled in. The mailbox taken down.

— Deb Travis

On the beautifully ornate metal gate were the words Le Paradise.

Pots of pansies and hydrangeas circled the white stones of the driveway.

The house stood on the right and a miniature replica was in the garden adjacent. Jenny’s playhouse. A rotted teddy bear adorned the doorway. It was missing an eye, the other replaced by a button.

The white, wooden garage still remained stuffed with excessive amounts of furniture and rugs. This was a shelter for treasures which did not fit in the house or the home.

A brass Tibetan lion was used to announce visitors. A simple rhythm of knocks…

Inside there were more treasures and a majestic portrait of my double moms hung above the marble fireplace. Entering the hallway, pictures and placards hung everywhere covering every available space of the green ivy wallpaper. One was crooked. I straightened it. Above my head, hung a myriad of glass icicles. Some missing, broken by an illegal basketball game. In the hall, countless rooms — studies, kitchen pantries — and a garden house filled with obscure and unique artifacts, relics and talismans. For the imagination. Not sprawling.

Tightly packed as if a dollhouse.

Spiral staircase, bedrooms upstairs. Jenny’s to the right of the landing. Mary’s at the end of the hall. Gothic canopy bed of curtains and ornaments strewn; clothes, wigs, books, magazines, newspapers, The Durham Herald, New York

Times, Daily Tarheel.

North Carolina letterheads covered with thank you notes.

— Amanda K. Miller

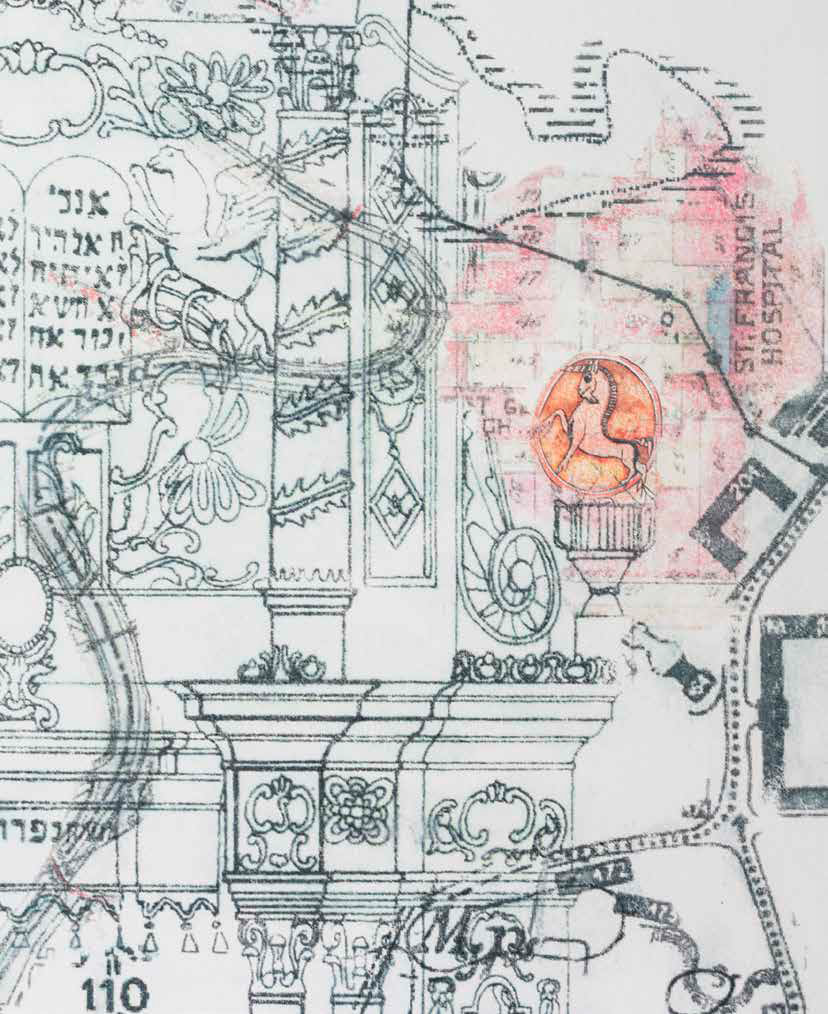

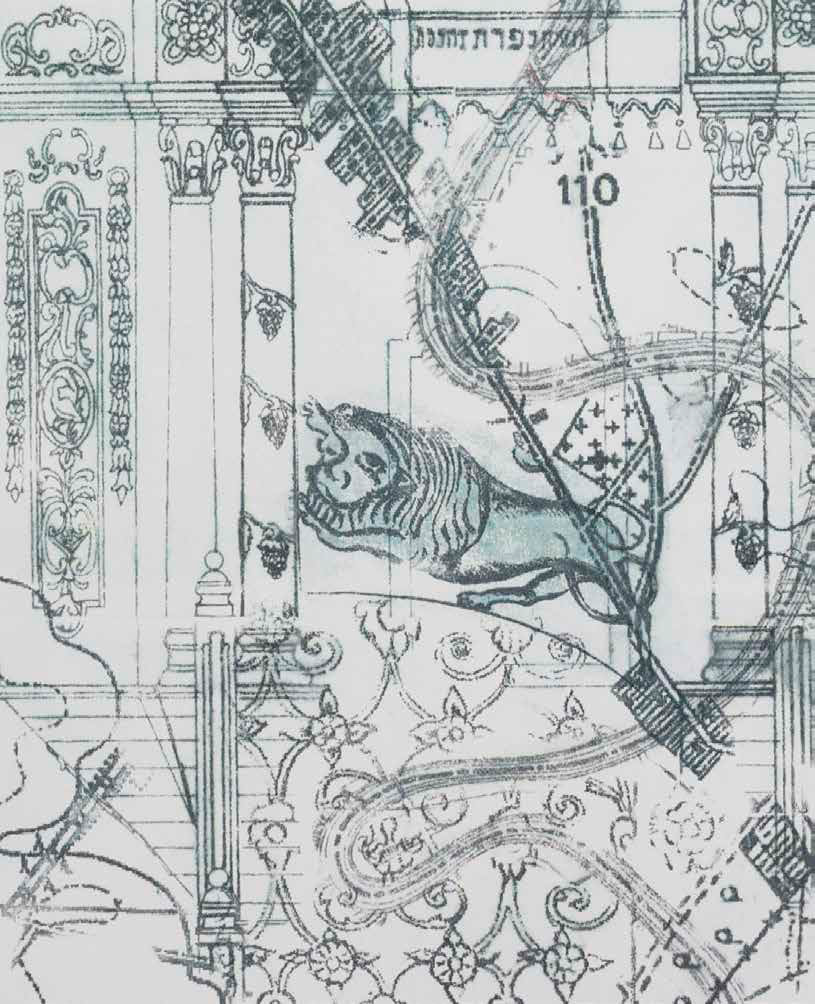

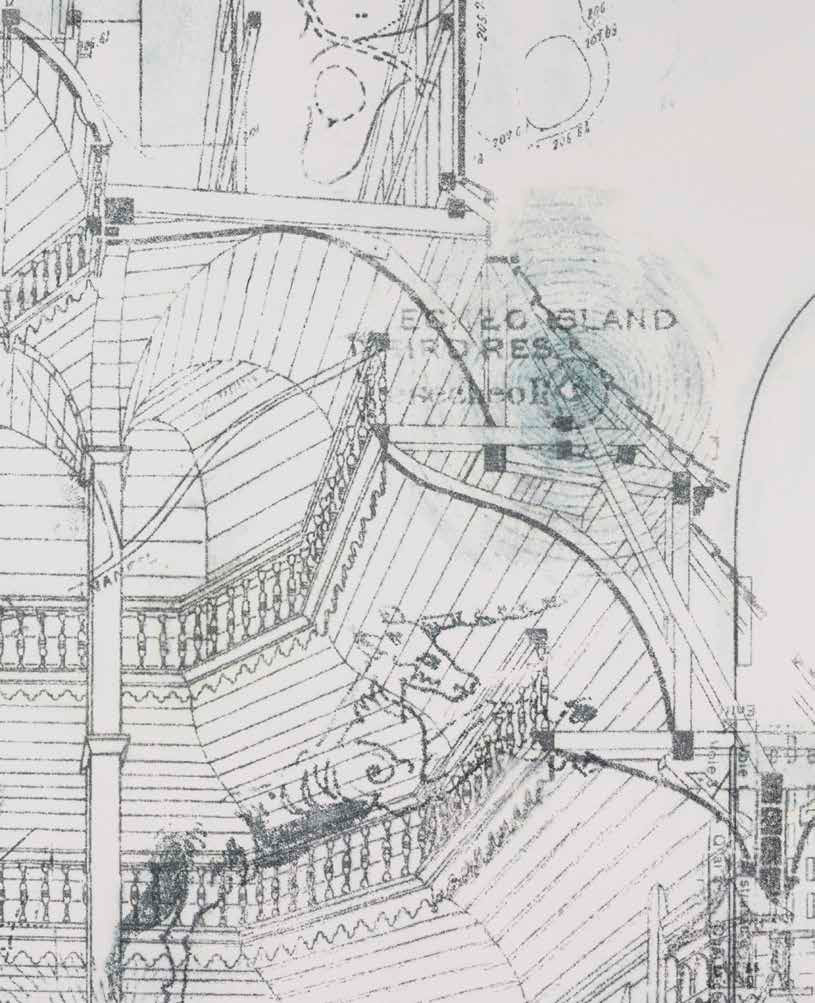

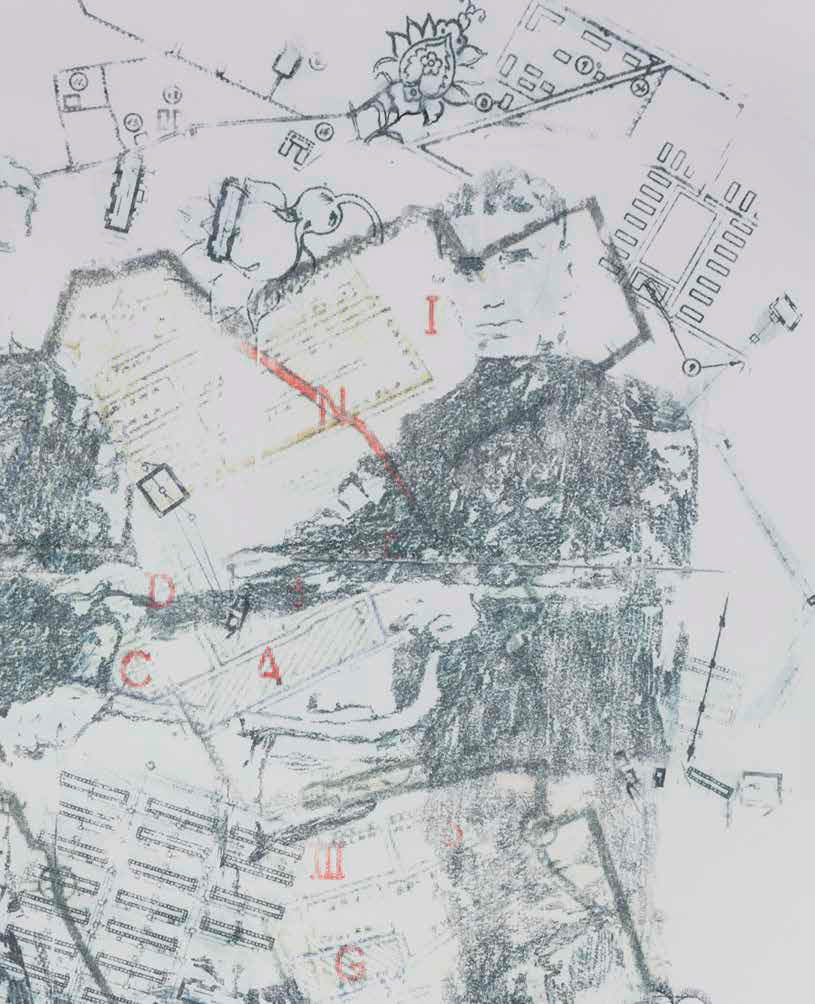

Maya Ciarrocchi is a New York City-based interdisciplinary artist working across media in drawing, printmaking, performance, and video. Her projects excavate disappeared histories as in her current work Site: Yizkor, where architectural renderings of destroyed buildings, maps of vanished places, extant Yizkor books, and viewer contributed writing become sources for documenting manifestations of loss. Ciarrocchi investigates how displacement writes itself into generational consciousness through the layering of architecture, maps, and memory in this work. The resulting compositions construct new, fantastical spaces that offer possibilities for healing and remembrance.

Ciarrocchi has exhibited her work in such New York venues as Abrons Arts Center, Anthology Film Archives, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, The Chocolate Factory, Equity Gallery, Kinescope Gallery, Microscope Gallery, and Smack Mellon, among others, and at Artisphere, (VA), Hammer Museum (CA), Borderlines Film Festival (UK), Moving Pictures Festival (CAN). She has received residencies and fellowships from the Baryshnikov Arts Center, Bronx Museum of the Arts (AIM), LABA: A Laboratory for Jewish Culture, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (Process Space, Swing Space), MacDowell, Millay Arts, New York Artists Equity, UCross, and Wave Hill (Winter Workspace). She has received funding from foundations such as Bay and Paul, Foundation for Contemporary Arts, Jerome Foundation, Mertz Gilmore, and project grants from Franklin Furnace Fund and MAP Fund. Ciarrocchi received a 2020 BRIO Award from the Bronx Council on the Arts and a 2021 Trust for Mutual Understanding grant to bring Site: Yizkor to Poland.

Ciarrocchi earned an MFA from the School of Visual Arts, New York, NY, and a BFA from SUNY Purchase, Purchase, NY.