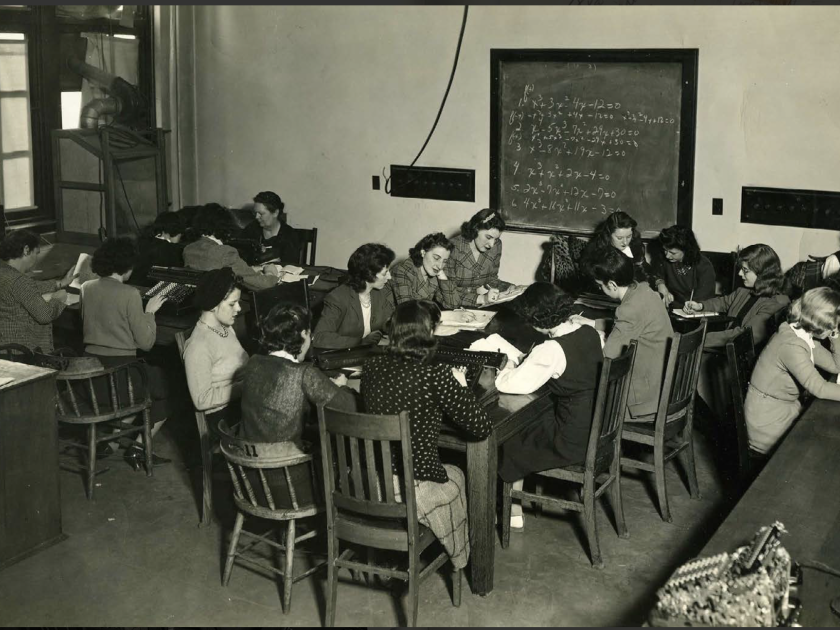

Mathematics for Ballistics Calculators, February, 1943, US Army Photograph

I’m fascinated by secrets. Who guards them? What are the stakes for revealing them? My first young adult novel, The Poetry of Secrets, was about crypto-Jews during the Spanish Inquisition. For them, keeping a secret was a matter of survival.

Then, while searching for inspiration for my sophomore novel, Trajectory, I came across a little-known group of women during World War II who helped lead the US Army to victory by doing something that was classified. For them, keeping a secret was a matter of duty. When I discovered that many of those women were Jewish, I knew I had to bring their story to light.

The year was 1942, seven months after the invasion of Pearl Harbor. Ten young women in sensible heels, skirts, and cardigans walked down a path on the University of Pennsylvania campus. They were between the ages of seventeen and twenty-five, but they weren’t coeds. Nor were they secretaries or nurses or teachers which was the only career option for women at that time. Their destination: an empty fraternity house taken over by the Moore School of Engineering.

Out of the ten women, one was Black and nine were white. Two were identical twins. Five were Jewish. They hailed from various cities across the Northeast. And what they all had in common was their skill with numbers. These women were part of the Philadelphia Computing Section (PCS). And they were the last of the human Computers.

The term “Computer” was first used in the 1600’s to describe men who tracked time with calendars. In the 1860’s, a female astronomer named Maria Mitchell was conducting an official US Coastal survey and called the people who worked for her, Computers. Then, in 1942, the US Army found themselves with a problem. They were overwhelmed by all the new weaponry that needed testing. Since the first world war, Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland had been conducting ballistics research with Computers, men who manually calculated the trajectory of a projectile. But now with most men enlisted, it was hard to find enough civilian men with mathematical backgrounds. The solution? Get females to do the job.

So the army contracted with the University of Pennsylvania, creating a satellite research hub at the Moore School of Engineering. The Junior Computers they recruited would be doing advanced math. The only caveat: they couldn’t tell a soul what they were doing.

In warfare, accuracy is crucial. Something I learned while writing this book was that gunners don’t just shoot at random. Firing tables are needed so soldiers know where the projectile will land. This is done using iterative approximations, a method of calculus. The arc of a bullet, missile, or shell is measured at multiple points along its trajectory, taking into account such factors as distance, altitude, wind, angular velocity of the earth, latitude, azimuth, relative velocity of sound, air density, drag function, and mass and diameter of projectile.

It’s painstaking and complex work. And the women rose to the task.

Though they were well compensated, their shifts could last up to sixteen hours a day. A typical shell trajectory involved thousands of individual calculations. It took up to forty hours to manually calculate just one sixty-second ballistic trajectory. And because the types of artillery were constantly changing, the women often had to throw out an entire week’s work. Their wrists were sore, their backs seized up, their heads pounded from the clicking and clacking of the desktop calculators. During the summer, salt tablets were on hand to prevent dehydration.

It wasn’t all toil, though. They did manage to have fun, going dancing at the Stage Door Canteen, picnicking near the Schuylkill River, and exploring museums.

Of course, not all one hundred members of the PCS were Jewish. But I wanted to tell the story of those who may have had other reasons to keep a secret, ones that went beyond duty. Those who wanted to do something, anything, to help their fellow Jews in Europe who were being forced into ghettos and gassed in such large numbers that many in America didn’t believe it was even happening.

Without the skills of these mathematicians, the Allies may not have won the war. Below is a snapshot of a few of these real-life Jewish women who were Computers.

There was Adele Katz Goldstine (not pictured), a fast-talking Brooklynite who smoked a pack a day. As Senior Computer, Adele was the main recruiter for PCS. She held a masters in math from University of Michigan and educated dozens of young women in graduate-level numerical analysis for trajectory calculations. She also wrote the technical manual for the first digital numerical computer, ENIAC.

The third floor PCS girls

Doris and Shirley Blumberg were identical twins. Recruited from the prestigious public school, Philadelphia High School for Girls, they were shining stars of the math club. Their mother volunteered for Jewish charitable organizations, and though she didn’t go to school past eighth grade, she told her daughters, “You can’t make it in this world without an education. I didn’t have the opportunity, but you do.”

Marlyn Wescoff graduated high school at age sixteen, then entered Temple University teacher’s college. Although her family struggled for money (Marlyn owned a total of two dresses and while one was being washed, she wore the other), they listened to music, read books, and talked politics at the dinner table every night. At graduation, the dean of Temple University warned the Jewish students, “Don’t look for any jobs in the suburbs. No one will hire you. Stay in Philadelphia or Pittsburgh.” Marlyn didn’t want to be a teacher. She knew how to work an adding machine and got a job crunching numbers at the Moore School before she became a Junior Computer.

Ruth Lichterman’s parents were Russian immigrants. Her father was a Hebrew school teacher. She attended Hunter College, hoping to major in math. During her first summer after freshman year, she planned to take a waitressing job at Camp Copake in New York, an adult summer camp for young Jews in the city. But then she saw the recruitment ad for PCS in her local paper.

Gloria Gordon worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in ship construction and then moved to Philadelphia where she got a job at the Moore School. Later, she joined the programming team of the ENIAC. In 1947, she transferred to Aberdeen Proving Ground to work on another secret project which may or may not have been part of the Manhattan Project.

The Junior Computers in my book, Trajectory, are fictional amalgamations of these women. And because I love secrets so much, I decided to give one Computer, our heroine Eleanor, a second secret, besides the classified one.

You’ll just have to read the book to discover it.

Numerical Analysis for Ballistics Computers, February 1943, US Army Photograph