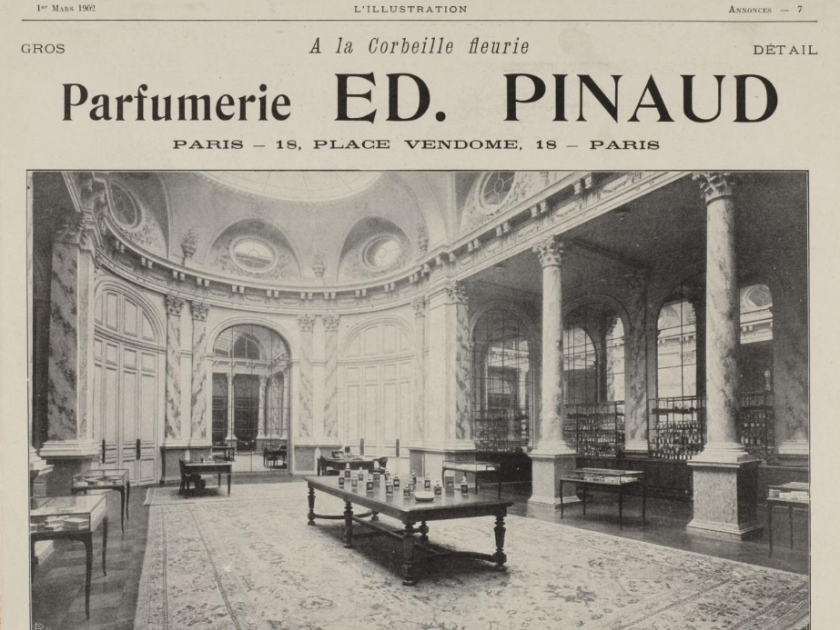

Advertising published in L’Illustration, Paris: 1st March 1902; Bibliothèque Forney (Paris), vol. L’Illustration, 1902, 1.

Most of the intrigue in my novel The Perfume Thief, set in WWII Paris, hinges on a fictitious journal of ingredients and formulas of Jewish parfumier, Monsieur Pascal. A master “nose,” and a genius of chemistry and business, Pascal disappears in the first few days of the occupation, leaving behind riddles, symbols, and a few clues to be discovered in a bottle of eau de cologne. Though Pascal is entirely fictional, I looked to the true stories of Jewish perfumers and couturiers who contributed significantly to the history of twentieth ‑century scent and the international culture of fragrance.

While the history of perfume tends to be as ethereal and elusive as the fragrances themselves — and official company histories as fanciful as the descriptions of the scents they bottle — the stories of these Jewish perfumers demonstrate a resilience, instinct, risk, and uncanny insight into the tastes and influence of women consumers.

Headshot © Michael Lionstar

Pierre and Paul Wertheimer, Parfums Chanel. Much has already been written about the savvy and expertise of the Wertheimer brothers, who bought Parfums Chanel in 1924 and built it into the brand it would become. As WWII threatened all of Europe, they anticipated the Aryanization laws that would rob the Jews of Paris of their businesses and properties, and they arranged for a transfer of Parfums Chanel to a non-Jewish Frenchmen, moved to New York, and started a subsidiary of the company. Coco Chanel, who originally sold the scent for a profit share of 10 percent and had always felt she’d been swindled (despite the fact that the deal made her one of the richest women in the world), sought revenge; the New York subsidiary would only owe 10 percent to Parfums Chanel, and Coco’s 10 percent would trickle from that. As Rhonda Garelick writes in Mademoiselle: Coco Chanel and the Pulse of History: “To Coco, from within her protective bubble of the Ritz, this looked like the one war atrocity she needed to address. … She was confident that her Nazi connections would win the day for her.” But she was foiled; the Wertheimers had carefully orchestrated the transferral of the business, and had also expertly arranged for covert access to the flower essences of Grasse, France, vital to the integrity of Chanel No. 5.

Ernest Daltroff, House of Caron. At the heart of Daltroff’s legend is a love story or, quite possibly, an apocryphal romance that makes for a livelier legacy than a chaste business partnership between two talents. Either way, Daltroff worked closely with Félicie Wanpouille — true lovers or not — to create some of the most admired perfumes of the twentieth century. He bought a shop with the name “Caron” already attached and hired Wanpouille, a dressmaker, who designed the bottles, applied for trademarks, and tended to other concerns of art and business. (They would eventually marry, but not each other.) Among their early creations was N’aimez Que Moi in 1916; translated as “Love only me,” the perfume has alternately been attributed to Daltroff’s message in a bottle to Wanpouille, and as a tribute to the women sending their lovers off to battle in WWI. Other creations included Tabac Blond (1919), which the current Caron catalog describes as “evoking the cigarettes smoked by the flappers of the Roaring Twenties,” by fusing “the intense scent of leather with its carnation and iris heart.” In one fell whiff, Tabac Blond spoke to the character and style of emancipated women, while also tantalizing with a tobacco perfume that ingeniously disguised the lingering stench of cigarette smoke.

Anaïs Nin favored one of Daltroff and Wanpouille’s most famous scents; she wrote in her diaries: “I should not be using ink but perfume. I should be writing with Narcisse Noir…”

Daltroff, like the Wertheimers, fled Paris as the Nazis neared; the House of Caron, as with Parfums Chanel, was at risk of Aryanization. In a 2011 interview with the perfume website ÇaFleureBon, Caron’s then-president Romain Alès said Wanpouille struggled to keep the business for Daltroff, and benefitted from the sympathies of the Francophile German officer put in charge of the company’s case file. In 1941, Daltroff died, which seems to have led to Wanpouille taking ownership, though some American patent office bulletins still list Daltroff as the owner of Caron Corporation in 1943. In any event, the company lore notes that Daltroff had intended on creating a perfume inspired by the sight of the Statue of Liberty as he reached his new home, but died before he could do so; in 2000, Caron released Lady Caron in recognition of that intention.

“Paris again is Paris,” read a full-page ad that ran in a December 1944 issue of Vogue. There was no illustration, only text, which demonstrated some indifference to where the sentences began and ended — a few missing periods, and lower-case letters where upper-case should be: “We are looking forward to bringing back the entire line of Caron perfumes to this country where they have enjoyed such widespread acceptance. … soon we hope.”

Company lore notes that Daltroff had intended on creating a perfume inspired by the sight of the Statue of Liberty as he reached his new home, but died before he could do so.

Jacques Heim, House of Heim. While only in his twenties, Heim transformed his family’s fur business into an internationally renowned fashion house. Initially his perfumes were only sold to the customers of his couture, but he did eventually establish Parfums Jacques Heim for worldwide distribution of fragrances that included J’aime, Alambic, and Monsieur Heim. He applied a logo to his perfume labels and boxes: a sharp-eared, Art Deco fox with an intimidating squint. In the 1960s, late in his career (and late in his life; he only lived to be sixty-seven), the Sydney Morning Herald quoted Heim as saying that perfume is an “invisible diaphanous scarf which completes an ensemble.” Heim left Paris during the war, moving to the Riviera, and though his business was overtaken by the Germans, they maintained Heim’s loyal staff. House of Heim was listed as one of the “old houses which are still going strong” in a 1944 edition of Vogue, followed by a parenthetical editor’s note: “No one knows whether actual heads of these houses are working in Paris — Mme. Schiaparelli has been in America since 1940.”

In actuality, Heim continued to pop in and out of Paris with falsified papers. And, according to his obituary in The New York Times, he “cooperated in gathering food and arms and secreting these for the large anticipated parachute drop” to assist in the liberation of France. Heim’s wartime experience was book-ended by two telling reports in The New York Times. “Even in peacetime every woman loves a soldier,” Heim told the paper in December 1939, in discussing a new, military-inspired collection: officer’s jackets and epaulettes done-up in colors of khaki and air-force blue. In a March 1945 article, the paper reported Heim’s reopening of the couture house “after four years of enforced absence,” with a collection in bland colors, due to dye restrictions. “Their opening display is discreet but in good taste,” the Times reported.

Roger Goldet, Ed. Pinaud. In the 1930s, Goldet took the reins of a company that had been owned by Jewish perfumers for decades. Emile Meyer was a Jewish businessman who partnered with perfumery founder Édouard Pinaud in the nineteenth century, taking over the company upon Pinaud’s death in 1868 and keeping the name. Ed. Pinaud advertised its perfumes — Iris-Blanc, Violette de Parme, and Aurora-Tulip — in the very first issue of Vogue in 1892. Along with Victor Klotz, his son-in-law, Meyer built the company into an international success, a legacy passed along to Klotz’s sons. Goldet’s exact involvement is unclear, though most sources (including the current Pinaud Paris website) credit him with taking the company in a new direction. A few society news columns made mention of his visits to the United States; one, in 1935, gave his title as vice president of the House of Pinaud, and one the following year called him “a tall handsome young Frenchman, executive of a French perfume house.” If Goldet did own Pinaud, the war seems not to have slowed him down; Pinaud introduced several new fragrances in 1943 and 1944, some seemingly inspired by war: Captive, Her Secret Weapon, Boomerang. The perfume Ammunitia was sold in bottles shaped like bullet casings. One ad in 1943 labeled Ammunitia “parfum militaire” and noted that it was “dedicated to the brave women of America”; a newspaper ad in 1944 said “it reflects the trend of the day.” Goldet also introduced a perfume called Obsession in 1944, a trademark eventually acquired by Calvin Klein.

A full-page ad in Vogue that ran in the summer of 1944 just prior to the liberation of France seemed to indicate that Pinaud’s American branches were active in keeping the company in production. The ad featured a portrait of Place Vendome crisscrossed with barbed wire above the copy: “Imprisoned City: France is captive, but tyranny never can destroy its ineffable charm! The fragrances that have given pleasure to the world have escaped and now are distilled for you here, in the century-old tradition that has made the name of Pinaud synonymous with exquisite refinement.”

Timothy Schaffert is the author of five previous novels: The Swan Gondola, The Coffins of Little Hope, Devils in the Sugar Shop, The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God, and The Phantom Limbs of the Rollow Sisters. He is a professor of English and Director of Creative Writing at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and he writes the column “The Eccentricities of Gentlemen” for the popular lifestyle magazine Enchanted Living.