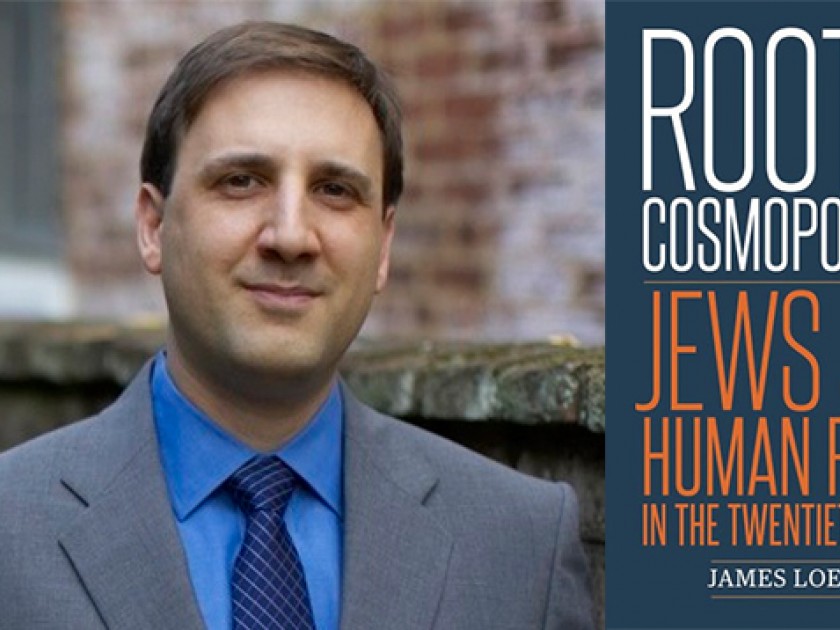

James Loeffler’s recent book, Rooted Cosmopolitans, compares two leading strategies of twentieth-century Jewish activism: one emphasizes collective rights for Jews as a minority group; the other focuses on advancing human rights for all in order to best protect the rights of Jews. Bob Goldfarb spoke with Loeffler about the implications of those strategies today.

Bob Goldfarb: It seems that there’s always been a tension between the view that there needs to be a Jewish state, and the idea that it’s possible to secure the rights of Jews as a minority in the countries where they live.

James Loeffler: I would put it differently. Among Jewish socialists and others, there was a strong desire to integrate, and the sense that Zionism marked us as “too different.” But for the people in the story I’ve told, Zionism wasn’t either/or. It wasn’t either “we stay here” or “we go.” These leaders in Eastern Europe felt that we needed to protect ourselves as individuals and as a people in the Diaspora—and also wanted to have a homeland like other nations. They felt that if we don’t have a country of our own, we can’t advocate for rights in the countries where we live.

BG: At the beginning of [minority rights advocate] Jacob Robinson’s career, in Lithuania, he defended the importance of minority rights for Jews, and at the same time said he was a proud citizen of Lithuania. It seems similar to the way American Jews describe themselves. But then he left Lithuania. Did his point of view change?

JL: It didn’t change that much. He left Lithuania, but it was because the Soviets invaded. More than he was concerned about Lithuanian anti-Semitism, which was very real, he was especially concerned with the Communist threat to Jews, and to everyone in that part of the world. He stayed in Lithuania, even after he moved his family abroad, to help the Jews who had fled Poland in 1939, and also because he was still friends with many people in the Lithuanian government. He was hyper-rational, and he always said we need to view the world as clearly as possible in terms of what’s going to happen.

BG: In present-day Poland, the ruling Law and Justice Party isn’t so friendly to Jews. What do you think Jacob Robinson’s take, or lesson, would be?

JL: Jacob Robinson felt that the Jews of Europe were not making enough use of the rights they had. Many Jews were afraid that speaking out would trigger another wave of anti-Semitism, and accusations that they were disloyal. They felt they should keep their heads down and hope it would all pass. Robinson, on the other hand, felt that the anti-Semites would think what they were going to think anyway.

As anti-Semitism comes more into the open in Poland today, his lesson would be that Jews should use every means at their disposal, and not be afraid to make claims against the country where they live — and to seek solidarity with Jews elsewhere. Another lesson is that we should be accepted for who we are, and not feel that being religiously, culturally, and linguistically different is somehow wrong.

BG: You used the word “solidarity.” That’s very different from the approach of Jacob Blaustein of the American Jewish Committee, isn’t it? He didn’t talk about solidarity, but rather the human rights of individuals.

JL: That tradition was also about solidarity, but much more about “let’s find solidarity with other groups in American society. Let’s build a partnership with them, not emphasizing how we may be different from other minority groups.” So it is a very different approach, an American liberal approach that was not comfortable with too much Jewishness — too much ethnic Jewishness, too much Jewish religiosity.

I don’t think they were assimilationist. They were proud of their Jewishness; they just weren’t comfortable with the idea that Jews should be seen as so different.

BG: Does that spring from a kind of anxiety about difference?

JL: I think it absolutely does. They felt that the more Jews seem like other Americans, especially other white Americans, the easier it will be for Jews. The American Jewish Committee was deeply committed to civil rights and to American liberalism. They also felt that Jews should not stick out too much; we shouldn’t appear too tribal.

BG: It seems as though the American experience is similar in some ways to that of German Jews, who famously called themselves “German citizens of the Jewish faith.”

JL: I think so. It’s striking, when you look back at why Blaustein and the American Jewish Committee were ambivalent about or even hostile to Zionism, that they spent very little time talking about conflicts between Jews and Arabs. They had a fear that if they talked about themselves as a nation — if they said we’re something more than just a religious faith — then we would be triggering more anti-Semitism, drawing more accusations of disloyalty. That was something they shared with the German Jews.

BG: Has that attitude made its way to American Jews today? Do you think most American Jews are no longer apprehensive about difference, or is there a large segment that still holds onto the idea that we shouldn’t be too different?

JL: I think it’s very much there. I think we can draw a line between that earlier period and a certain American Jewish mentality today. In spite of a greater self-confidence, there’s still a strain of Jewish thinking which is hesitant to foreground Jewish identity. There’s still a certain segment that is less comfortable with the thicker forms of ethnic, cultural, or national Jewish identification, and resist the idea that they’re part of a “Jewish nation.”

BG: How does that square with the stance of a lot of American Jews in favor of activism on behalf of other self-identified groups — African-Americans, Palestinians, LGBT people? They don’t categorically reject bold group identity, just in the case of Jews.

JL: It comes from the kind of early mid-century position taken by the American Jewish Committee, and other groups like the American Jewish Congress, which says that when we advocate for others we are protecting everyone. We’re ensuring the fate of democracy, we’re making democracy more inclusive, and this will benefit us.

The critique of that is that it can lead to an imbalance in how we think about who we care about. We’re at a point now, because of the politicization of human rights and the polarization that has taken place, that these things seem in tension with one another in a way that they weren’t before.

BG: Is there any sort of paradox in the stance of a group like Jewish Voice for Peace, which identifies as Jewish while advocating for Palestinians?

JL: I think there is a paradox, and I try to expose it in the book I wrote. That very quest for human rights and justice has deep Zionist roots. To pretend that this activism comes from a rejection of the Jewish experience, and an embrace of the other, is to inflict a certain violence on history and on what really happened. It’s pretending that Jews became cosmopolitan, and that required them to check their Jewishness at the door. There’s an amnesia there.

There’s an ethical problem, too. The people I’ve studied understood that you can best advocate for these concerns by recognizing your membership in this collective experience we call the Jewish people. That way you’re actually better able to understand the needs of the Other.

The first rule of the Middle East is that you have to come as who you are. That means you can’t sidestep the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. You have to work through the framework of being part of the Jewish people — pushing, if you want, for the Jewish people to change. If you want Israel to change its policies, work through Israel rather than trying to delegitimize Israel and treat it as an entity that you have no relationship to. You don’t get to simply join up with the Palestinians.

BG: Was Peter Benenson [founder of Amnesty International] a precursor to the Jewish Voice for Peace point of view? His goal was to be universalist and enforce human rights. At the same time, Amnesty was criticized for being particularly interested in alleged human rights abuses by Israel, while it declined to investigate other countries in the Middle East in the same way. It seems to be an extension of universalism to take that next step.

JL: I think that’s true, and it’s an interesting genealogy. Just as now, there was a lot of diversity, a lot of Jewish pathways. Benenson’s story shows you can cut yourself off from the Jewish religion, and you can dream, but the Jewishness in the politics of it doesn’t go away. Benenson tried to reject all national and tribal identity, becoming a Catholic to do it. I think that’s part of the explanation of why human rights, as it chased more and more after universalist ideals, came to focus on Israel. It saw Israel as a fundamental obstacle to those goals.

It also has to do with what we could call a political theology: human rights as a kind of religion. It can replace other religions and other kinds of political commitments. Something of Amnesty International’s origins, and its explicit rejection of Zionism, colors its attitudes, and its determination to finally resolve the Israeli conflict through its own intervention.

Amnesty had a vigorous internal debate about exactly these questions. Some members felt it was wrong to focus on the Palestinian conflict, because “we don’t work in war zones, and that’s not our expertise, and we don’t support prisoners who endorse violence.” Others said, “No, we have to do this.” It’s important to recapture that complexity.

BG: In the epilogue to the book, you wrote: “The professional human-rights community speaks the language of long-distance solidarity, and cosmopolitanism. It sees injustice, crisis, and atrocity, and favors networks and crowds instead of nations and states.” If power is decoupled from idealism, and if politics are made irrelevant to the project of human rights, then human rights activists would become practitioners of rhetoric and symbolism rather than achieving actual results. Is that what you meant by human rights becoming a religion? Is there an implicit belief that faith in human rights will itself bring salvation and redemption?

JL: I do think there’s a crisis for human rights. If it’s only about rhetoric, or norms, and you have powerful states which ignore them and become completely resistant, you can call them names, but that doesn’t force them to change. Then human rights doesn’t have the power that it would aspire to have.

That’s a message that might be surprising, especially in the Jewish sphere. About those involved with Israeli activism who criticize and try to delegitimize Israel, I believe that it doesn’t actually have the power to change what the Israeli government is going to do. For those people who deeply care about the Palestinians, human rights activism is not going to make up for what the Palestinians don’t have, which is a state. Human rights can’t replace citizenship.

It also can’t stop something like Syria. We see now that outrage about Syria on the internet can’t stop the war there. It can’t be stopped by people signing petitions or talking about the atrocities that are being done. The war will be stopped when governments decide to intervene. I think human rights activism is waking up to that.

Bob Goldfarb is President Emeritus of Jewish Creativity International.