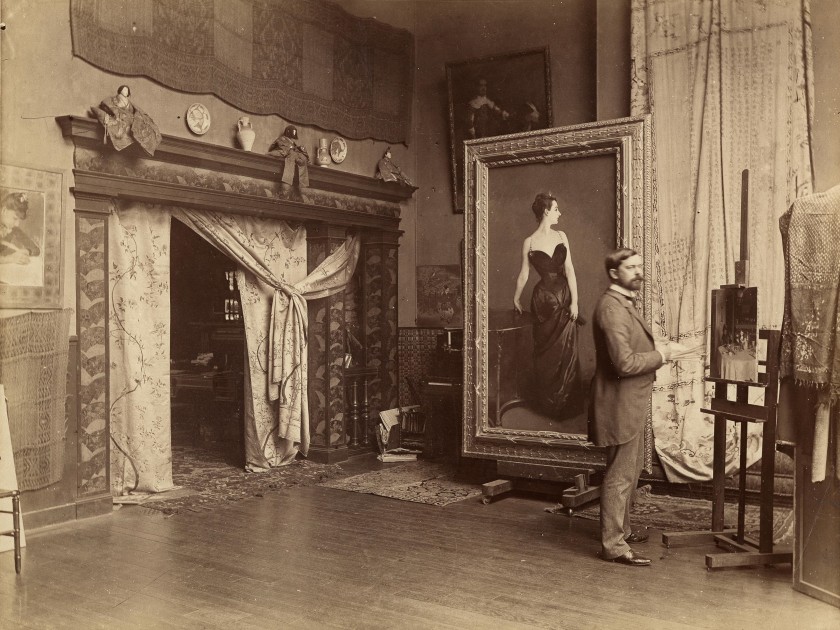

John Singer Sargent in his studio with Portrait of Madam X, Photo by Adolphe Giraudon, 1885

In 1931, W. Somerset Maugham, the author of The Painted Veil, Of Human Bondage, and many other works of fiction, published a novella called The Alien Corn, about a family of wealthy British Jews. I came across it while writing a book of my own about a family of wealthy British Jews, the Wertheimers, and their portraits by John Singer Sargent; the book, to be published in November, 2024, is called Family Romance. A Wertheimer descendant thought that Maugham had based one of his characters on a member of her family.

The eminent London art dealer Asher Wertheimer and his wife had ten children, and Sargent painted them all, singly and in groups, between 1898 and 1908. At one point he mock-complained to a friend of being in a state of “chronic Wertheimerism.” This series was the artist’s largest private commission, which made Asher his greatest patron.

Probably I was naïve to be surprised, in the course of learning about all these people and paintings, at how ineradicably “other” Jews looked to dominant cultures on both sides of the Atlantic. Critics and casual viewers alike described the figures in the Wertheimer portraits as alien, foreign, exotic, “oriental”— meaning eastern, not western, not “us.”

When London’s New Gallery showed Sargent’s Essie, Ruby and Ferdinand, Children of Asher Wertheimer, in 1902, a writer for The Spectator pronounced the artist “a great painter not merely because of his enormous technical power, but because he can penetrate below the surface and reach the heart of his subject.” The heart of the subject, to this critic, was its artifice and oriental tone: “the air we feel smells of scent and burnt pastilles…. the moral atmosphere of an opulent and exotic society has been seized and put before us.”

Another critic went further: Sargent had adopted “a more decorative scheme, a more luscious chord of color than usual,” and the three figures, “variously and gaudily dressed … lie about among cushions like odalisques in a harem, and are sprinkled over with dogs.” Asher hung the painting over the mantelpiece in the family dining room.

______

The title of Somerset Maugham’s novella, The Alien Corn, refers to Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” and the biblical story of Ruth, widowed in a foreign land:

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn

Most of the people in Maugham’s fictional Jewish family have tried to erase their origins, changing their surname from Bleikogel to the delectably denatured Bland. One, however, has kept his name and Jewish identity: the cultured, rich, socially brilliant Ferdy Rabenstein, now in his seventies. The narrator of Alien Corn describes Ferdy:

It was not hard to believe that in youth he was as beautiful as people said. He had still his fine Semitic profile and the lustrous black eyes that had caused havoc in so many a Gentile breast…. He wore his clothes very well, and in evening dress, even now, he was one of the handsomest men I had ever seen…. Perhaps he was rather flashy, but you felt it was so much in character that it would have ill become him to be anything else.

“After all, I am an Oriental,” he said. “I can carry a certain barbaric magnificence.”

Ferdy’s sister, née Rabenstein, had married Alphonse Bleikogel, “who ended life as Sir Alfred Bland, first Baronet, and Adolph, their only son, in due course became Sir Adolphus Bland, second Baronet.” Sir Adolphus and his wife, Muriel (formerly Miriam), live on a vast manicured estate in Sussex. Their eldest son, George, is slated to inherit the family fortune, go into politics, be the perfect English gentleman. Yet George has no interest in money or politics. Sent down from Oxford with huge debts in spite of a princely allowance, he wants only to become a professional pianist — an aspiration that is unacceptable to his parents.

During the family battle over his future, George learns for the first time that he is Jewish. His grandmother – Ferdy’s sister – persuades the young man’s parents to let him study piano in Germany for two years, then come back to perform before a disinterested expert. If, in the expert’s opinion, George shows real talent, they will not only not stand in his way but give him every advantage and encouragement. If, however, he proves to have no true gift or prospect of success, he will give up music and comply with his father’s wishes.

George agrees. In Munich he lives like a bohemian, takes piano lessons twice a week, practices ten hours a day, and spends all his free time with Jews. After two years, he returns to England as promised. Ferdy Rabenstein brings the (fictional) concert pianist Lea Makart, “acknowledged to be the greatest woman pianist in Europe,” to hear him. George plays Chopin. When he finishes, he turns to face Makart without speaking.

“What is it you want me to tell you?” she asked.

They looked into one another’s eyes.

“I want you to tell me whether I have any chance of becoming in time a pianist in the first rank.”

“Not in a thousand years.”

In the silence that follows, her eyes fill with tears. She offers to introduce George to (the not-fictional) Paderewski for another opinion. George smiles, says that will not be necessary.

He walks out onto the terrace, where his father joins him. Sir Adolphus has triumphed but cannot bear the anguish of the son he adores with “such an unEnglish love.” In short order he relents, offering to send the young man back to Munich for another year – or around the world.

“Thanks awfully, Daddy, we’ll talk about it. I’m just going for a stroll now.” George kisses his father on the lips, then makes his way to the gun room, where he shoots himself through the heart.

The Alien Corn was made into a film in 1948, starring Dirk Bogarde as George Bland. Somerset Maugham knew one of the Wertheimer daughters, and it is possible that he drew parts of his novella from her family’s story. At the risk of being coy, I will leave it to readers of Family Romance to discover which Wertheimer may have served as a model for one of the figures in Alien Corn.