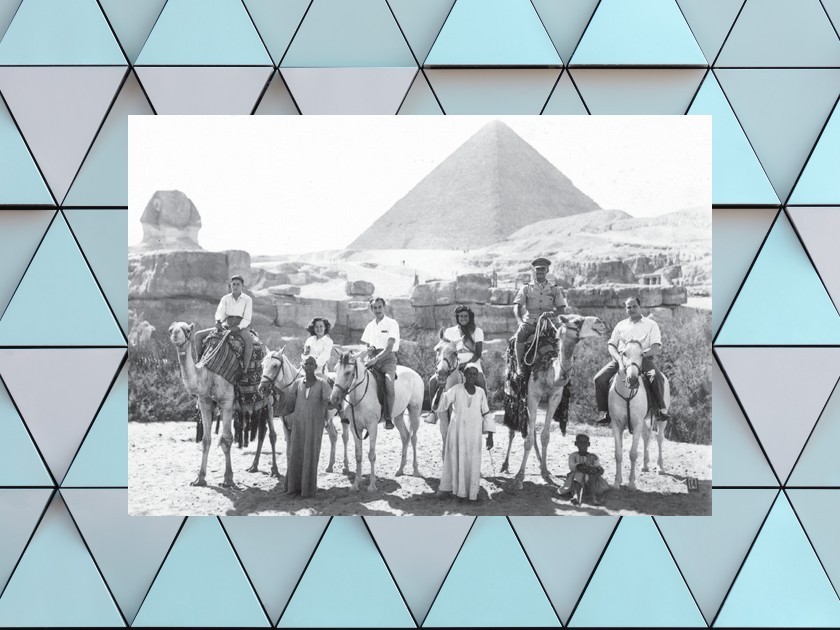

The author’s mother on horseback in front of the pyramids.

“What kind of a Jew are you? ” My little classmates in 1950s Brooklyn would challenge me when I confessed that my parents didn’t speak Yiddish, I’d never tasted gefilte fish, and we spoke French and Arabic at home.

“Egyptian,” I’d stammer. “We’re Egyptian Jews,” though my answer mystified me as much as it did them.

“There are no Egyptian Jews,” would come the inevitable retort. “All the Jews left Egypt with Moses. Isn’t that what Passover is about?”

I knew no other Jews from Egypt aside from a handful of relatives, and my parents were reluctant to speak about their past. I knew only that they’d left their home in Cairo in 1951, correctly fearing that with the establishment of the State of Israel and the concurrent rise of Arab nationalism there would be no future for us there. I was eighteen months old at the time. All I retained of our life in Egypt was the imprint of my parents’ grief and fear; theirs was a break that brooked no backward glances.

And so I grew up hungry for stories, for some tangible link to our origins; I was met with a void. In school we read books by American and British writers; on the streets I played with Ashkenazi Jewish and Irish and Italian Catholic children. Unable to find my reflection, I flung myself into full-on assimilation: I would master the English language, I would eat bagels and cream cheese and lox, I would become American. Eventually I earned a Ph.D. in English literature and moved to Norman, Oklahoma, for my first teaching job. There I found myself still lamely explaining what kind of a Jew I was, even as I began my more deliberate quest to learn our history — and to share that history with others.

America in the second half of the twentieth century was drenched in the literature of Ashkenazi Jews, with stories about the Holocaust, shtetl life, growing up Jewish in Chicago, Brooklyn, or Newark. Where was our literature? Where were our stories about Arab-Jewish lives in North Africa? (I hadn’t heard then about Jacqueline Kahanoff or Edmond Jabès, brilliant Egyptian Jewish authors who never made it into the mainstream.) Where were the tales that described what happened to our communities? Why were there no celebrated Egyptian, Moroccan, or Algerian Jewish writers, like the Polish, German, and Russian Jewish authors who’d gained such well-deserved acclaim?

The author’s grandparents, aunts, and uncles on a balcony in Cairo.

At long last, in 1993, André Aciman published Out of Egypt, and it seemed we’d finally gained a seat at the table of Jewish literature. But Aciman’s elegant memoir — about a wealthy, eccentric, cosmopolitan family in Alexandria — did not fully resonate with what I’d gleaned of my family’s more modest and conventional lives in Cairo.

Gini Alhadeff’s beautiful 1997 The Sun at Midday: Tales of a Mediterranean Family also seemed distant to me in its focus on a rich, worldly, Alexandrian clan whose members converted to Catholicism.

I grew up hungry for stories, for some tangible link to our origins; I was met with a void.

I decided I had to write our story myself. I questioned my parents and relatives. I insisted they speak to me and I began to piece together the fragments they shared. I traveled to Cairo and breathed the air, walked the streets that formed the backdrop of their lives. I read everything I could get my hands on. My memoir Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, an Exile’s Journey was published in 2008, around the same time as Lucette Lagnado’s The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit. More memoirs and a few novels followed, including Jean Naggar’s evocative Sipping from the Nile, and most recently her Footprints on the Heart. We were beginning not only to have a place at the table, but also to be setting the table ourselves.

Yet it wasn’t until I came across Tobie Nathan’s 2015 Ce pays qui te ressemble—A Land Like You—that I found my true literary home, the deep, mirroring connection I’d sought since childhood. The novel fully immersed me in the life of Cairo in the first half of the twentieth-century — my parents’ Cairo — in all its alluring, contradictory, maddening fervor. Nathan, an ethno-psychiatrist whose family left Egypt in 1957 when he was nine, had previously published an award-winning memoir, Ethno-roman. Although A Land Like You, was a wildly fictional free imagining of his parents’ milieu, it seemed to contain more truth than all the meticulously researched, nostalgic memoirs put together.

Perhaps because it was written in French, my first language, the novel brought me back to my earliest days, to the densely textured world my parents carried within them and conveyed to me despite their efforts to leave it behind. In Nathan’s characters, I heard and saw the speech and gestures of my own loudly expressive, forever meddling, constantly teasing relatives. This was not the genteel literary French I’d studied in high school and college, but the spoken French of our family — a colloquial French inflected with Arabic, Italian, and Hebrew. This was a French that sacrificed elegance and correctness for directness and candor. From the first scene where a young Jewish woman prepares ful mudammas, the ubiquitous fava bean stew we savored every Sunday in our home, I was hooked.

I immediately determined that this would be my next project as an emerging literary translator: I would bring Tobie Nathan’s exhilarating recreation of early twentieth-century Egypt to an English-speaking audience. Despite the challenges — finding a publisher, choosing the right words, reaching an audience — I never doubted that this was a task meant precisely for me.

The novel more than fulfilled its initial, tantalizing promise. In its pages I met rabbis and sheikhas, dancers and zbib-drinkers, peasants and pashas, heroes and villains. I heard the sounds of Egyptian music and smelled the scents of Egyptian spices; I felt warm breezes along the Nile and was dazzled by the desert sun. I encountered the real historical figures and events that determined my family’s fate, even while I shared the dreams and daily lives of the most ordinary folk.

I heard the sounds of Egyptian music and smelled the scents of Egyptian spices; I felt warm breezes along the Nile and was dazzled by the desert sun.

More than anything, Nathan in this novel is a fabulist, fabricating fantastical tales — like the infinite stories in the Thousand and One Nights, or the haunting fictions of Isaac Bashevis Singer — that play along the borders of belief while rendering timeless truths. The novel’s central characters live in the hara, the narrow, winding alleys of Cairo’s ancient Jewish quarter; they are poor, indigenous Jews who worship in crumbling synagogues and implore their rabbis to craft protective amulets and expel demons. Their presence in Egypt goes back centuries and might well have gone on for centuries to come, had not the world stage changed. As Nathan’s narrator proclaims, these Jews are “Kneaded from the Nile’s mud, the same dark color, native.” They live side by side with Muslims, knowing they could well be one: “Our tales fill their Qur’an, their tongue fills our mouth. Why are they not us? Why are we not them?”

My own family immigrated to Egypt from Syria and Iraq in the nineteenth century. We never lived in the hara, hardly associated with non-Jews, and spoke more French than Arabic. But as Nathan asserts in Ethno-roman, no matter where we came from or when we arrived in Egypt, no matter how we dressed or how we spoke, the ancient hara—for all the Jews of Egypt — is our origin, “notre source.”

Nathan means “source” in the sense of a living spring, “the place where we find the strength to regenerate ourselves,” the place where we are indissolubly bound to the land and its people. ‚And as he further specifies, “If one does not know one’s origin, or play a part in it, cultivate it, then it will wither away and dry up like a spring.… It’s not just the past that makes origins, but also the present and the future.”

As I read and re-read Nathan’s book — nearly committing all its 340 pages to memory — I found myself drinking daily from this refreshing source, bathing in it actually. A Land Like You granted me the history that history denied me. In sharing it now with others, my hope is to keep that history alive, so that no one will ever again need to ask me what kind of a Jew I am. With Nathan and his protagonist I can now proudly say, “Although I left Egypt, Egypt never left me.” In this one small way I hope to have helped Egyptian Jewish literature flow into the mainstream of Anglophone culture, allowing our rich, nurturing tales to flourish beside those of our beloved Yiddishkeit cousins.

Joyce Zonana is an award-winning writer and literary translator, born in Cairo, Egypt, and living in New York. Her memoir, Dream Homes: From Cairo to Katrina, An Exile’s Journey, recounts her own experience growing up as an immigrant in New York City. A Land Like You is her third translation.