Forty-five years ago, a small force of Israeli soldiers flew south over the Red Sea, skimming the territorial waters of a string of enemy states and rescuing nearly all of the 105 hostages at Entebbe, Uganda.

The story is well-known. But what few people realize is that those soldiers, many of whom served in the elite Sayeret Matkal reconnaissance unit (or the “Unit,” as the outfit is known), met with the prime minister and defense minister and, after being driven back to their base, simply ate, showered, congratulated one another on a job well done, and went home. The post-mission debriefing that is so crucial to all IDF special operations never happened. There was a meeting in the mess hall that afternoon during which some of the soldiers spoke of the mission, but it was conducted in front of the entire unit, including noncombat troops and guests, and was more of an entertainment than an interrogation of fact. The ritual of self-examination is how the IDF improves itself, how it determines precisely what happened in the field. But after the rescue mission in Entebbe, the country was in the throes of ecstasy, the majority of the soldiers involved in the actual hostage takeover were on the cusp of discharge from military service, the Unit was in high gear for a pending covert mission, and its former commander, Yoni Netanyahu — the man who had led the soldiers into action— was dead.

No one asked the other soldiers to step forward and recount what they had seen and done. The result of this oversight has been a decades-long fight over the facts. Who planned the mission? Was then-Lt. Col. Yoni Netanyahu right in giving the order to open fire on the Ugandan sentries, or had he risked the entire operation by disregarding the hard-earned advice of Major Muki Betser, who had lived in Uganda and trained the national guards? What about Betser himself? Is it true that he, the leader of the assault team, faltered on the way into the terminal, endangering the force and the hostages alike? Did the fact that he paused out in the open cause Netanyahu to step into the exposed area and pay with his life — or was that necessitated by the situation on the ground?

This book ultimately triumphs in detailing the way tragedy and elation can coincide, the way victory is often just a hair’s breadth from defeat, and the way historical fact is illuminated, rather than veiled, by myriad points of view.

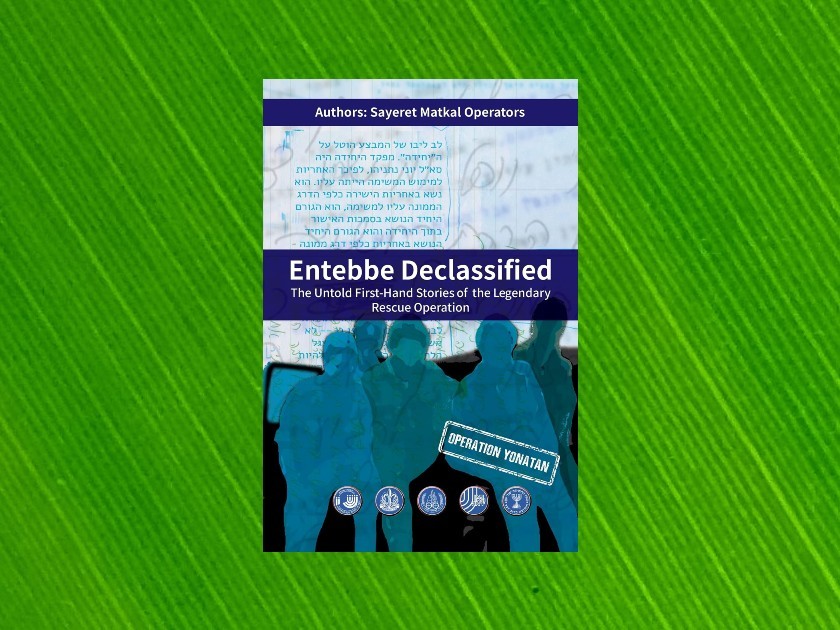

A new book, Entebbe Declassified, which I had the pleasure of translating, does not try to draw a single authorial conclusion. Instead, what it offers is a stage on which thirty-three of the soldiers who took part in the mission finally relay their experiences in their own words. The result is the most probing look at the most successful hostage-rescue mission of all times and a glimpse into an IDF ethos that may no longer exist.

I came away from the project with several insights.

1: The soldiers. These guys are as good as the legend. How disappointing it would have been to find them petty or jaded or crooked. But no, they are stellar.

2: Yoni Netanyahu. The portrait of the commander of Sayeret Matkal that emerges from this volume is fascinating. He was clearly a strange bird in the Unit. He read books; he spoke English; he’d been to Harvard. There were those who revered him for his courage and his poise under fire. And there were those who felt that he was distracted by personal affairs and ill-suited to the covert nature of the Unit’s work. The clash of opinion is most sharply brought into focus, I feel, in two testimonies. The first is by Master-Sgt. Dani Dagan, the oldest enlisted man in the Unit at the time. He describes himself as “a field worker from [Kibbutz] Mishmar Haemek, a guy who believes no one, an old fox who’s seen a lot,” and Netanayahu as “a professor, a believer, an innocent, a scholar.” And yet the two were close. Several weeks before the operation, Dagan called Netanyahu on Shabbat and said they needed to talk. Netanyahu invited him over. Whiskey was poured, and Dagan said he wanted to discuss what appeared to be a sort of mutiny brewing in the Unit. If Netanyahu thought the topic inappropriate, Dagan reasoned , he’d drain the whiskey and be gone. If he wanted to hear more, Dagan would share his thoughts. In his testimony, Dagan is vague on what precisely was said and what Netanyahu eventually decided to do, but it is clear that Netanyahu flew to Entebbe with this situation still weighing heavily on him.

The ambivalence toward Netanyahu is further illuminated in the riveting account given by then-Lt. Omer Bar Lev, who went on to command the Unit and today is the Minister of Public Security. In all of his years in uniform, Bar Lev writes, he never once used his connection to his father, a former IDF Chief of Staff who was a Cabinet member at the time of the mission. But on July 2, the night before the mission, Bar Lev, along with several other officers, decided that there was too great a discrepancy between the truth and Netanyahu’s presentation of the facts regarding the capacity of the Unit to carry out the mission. He finally got into a truck to drive to his father’s house and report the nature of the misrepresentation to him. But while he was driving, the hood of the trunk suddenly popped up, and after steering the vehicle off the road, he shut the hood and turned back around. In retrospect, he writes, Netnyahu was right. “Our point of view was … one-dimensional and mistaken.”

3. The sentries. The first Israeli plane landed alone, on a runway that was still lit. The paratroopers hopped off and marked the tarmac for the following planes. A Mercedes slid down the rear ramp, followed by a pair of Land Rovers. That, at the time, was the entire Israeli force on the ground. The soldiers regrouped and loaded their rifles. Around them the air was warm and lush. Many of the men recall the tropical smell of the night. Netanyahu guided the formation off the tarmac and toward the old terminal. On the way, as expected, a pair of Ugandan sentries manned a roadblock. They raised their rifles. Betser, sitting in the middle in the front seat, said it was only a salute. Netanyahu ordered the driver, Lt. Amitzur Kafri, to swerve right, toward the sentries, so that he could shoot them with his silenced handgun, as they’d practiced during pre-mission drills. Kafri veered right. Betser ordered him left. The Mercedes swerved again, the jeeps fishtailing in its wake. Netanyahu countered. Amitzur complied. The silenced pistol fire from Netanyahu and others eliminated one of the sentries, perhaps, but certainly not both. The soldiers in the trailing jeeps, realizing that they could not leave armed guards behind them, opened fire with unsilenced weapons and mowed down the guards. The terminal was awakened.

Betser and Netanyahu both made judgment calls in a moving car, near midnight, 2,500 miles from home. The acclaimed book Operation Thunderbolt by military historian Saul David hews closely to Betser’s interpretation of the events. But the overwhelming majority of those in the Mercedes that night — there were ten, fully loaded operators squeezed into the three benches — believes that Natanyahu was right to have given the order to open fire, even at the cost of jeopardizing the element of surprise.

4. The charge. There was a span of perhaps no longer than sixty seconds in which most of the operation was decided. The crux could almost be caught in a painting, so brief and condensed were the events. It was then that the force was stalled behind Betser, then that Netanyahu was shot, then that a single soldier, Staff-Sgt. Amir Ofer, sprinted alone towards the doors, charging through a seventeen-bullet blast of glass-shattering automatic fire. And then that his commander, Lt. Amnon Peled, sensing the immediate peril to his soldier, surged ahead, and killed the two German terrorists by the door just as they were in the act of swiveling their rifles toward Ofer’s back. For several long seconds, Ofer and Peled were the only soldiers in the room — a twenty-five-meter-wide hall, filled with over one hundred hostages and several armed terrorists.

This is the margin of error. It is so very slim. And this book, written by former soldiers who today are farmers and builders and high-tech entrepreneurs, is albeit unruly at times, layering testimony over testimony. But in my opinion, it ultimately triumphs in detailing the way tragedy and elation can coincide, the way victory is often just a hair’s breadth from defeat, and the way historical fact is illuminated, rather than veiled, by myriad points of view.