There’s a scene in my new novel, Someday We Will Fly, in which Lillia, my scrappy heroine, comes across a wall of books in her friend’s house. Lillia is a Polish Jewish refugee who has fled Nazi-occupied Warsaw and is surviving the war in Shanghai — the only place left in the world that will let Jewish citizens land. Lillia has managed to bring only a single book with her, and hasn’t seen anything nearly as luxurious as her friend’s shelf of books since arriving in Shanghai. The city is excruciatingly unfamiliar, and Lillia’s mother vanished before they were to sail, so Lillia’s life is almost unmanageably difficult. The sight of so many stories creates in her a jolt of sorrow at her own situation, and embarrassment of wanting something as badly as she wants to read and escape. But it also offers her what books so often offer us: stories other than the ones we’re currently living, templates for how our lives might ultimately be okay, and hope.

But it also offers her what books so often offer us: stories other than the ones we’re currently living, templates for how our lives might ultimately be okay, and hope.

Lillia gets to borrow as many books from that shelf as she likes (her friend Rebecca is generous and sees Lillia’s need), and I wrote that moment for Lillia because my book is about how we hang onto the possibilities of hope, love, and childhood in contexts as hideous as war. How do refugee families help their children come of age with any sense of normalcy or safety? One way is through stories. This scene is both optimistic and true; libraries were lifelines for the real-world Shanghai Jews I met and talked to, and whose own books I read while I was researching Someday We Will Fly. I spent seven summers in Shanghai, where I read, wandered the neighborhoods, and sifted through photos and objects at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum. But it was at home in Chicago that I had the almost miraculous fortune to meet Dr. Jacqueline Pardo, whose mother Karin Pardo (née Zacharias) was a Shanghai Jew.

Jacqueline saved an astonishingly comprehensive archive of belongings from her mother’s girlhood, and also hundreds of the more than 3,000 books her grandfather, Leo Zacharias, managed to carry from Germany to Shanghai with him. Getting to see and feel and, in some cases, flip through the actual books Leo Zacharias carried to Shanghai allowed me to imagine what their pages must have meant to refugees who otherwise would have had no way to read. For years, Leo Zacharias lent his books out, which I imagine not only formed a community, but also allowed that community to be in a literary conversation. Books let the refugees feel connected not just to each other, but also to human beings across eras. James Baldwin writes: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” I wanted Lillia, whose mother is missing, whose baby sister is almost incapacitated, and whose life is excruciatingly difficult, to have access to the simultaneously imaginative and very real hope that books can offer.

Originally, I was inspired to write Someday We Will Fly by some photographs I happened upon in the Shanghai Jewish Refugee Museum one summer when I was in Shanghai working on a contemporary project. The first photo was of a group of teenage boys, war refugees from Europe, like so many of the Jewish settlers who found themselves in Shanghai between 1939 and 1945. These boys were staring into the camera with the soulful, hollowed-out look of kids growing up in the deadening context of war. They also looked simply like boys, mischievous and sweet. Stunningly, they were dressed in polo shirts with school insignias and little tennis rackets printed on the chests. These were teenagers who had arrived in Shanghai having fled both unspeakable terror and everything that was familiar to them. Yet their grown-ups, on top of managing to keep them safe and feed them, had made a school, a table tennis table team, and shirts for them. Those tiny insignias seemed iconic to me of how human beings save each other and their children. Of course they were also a very literal symbol of the resilience refugees demonstrate — in ways both too small to be seen and too vast to be measured.

Next to that image was one of two toddlers, girls holding rag dolls. The girls were in rags themselves, but someone who loved them, their parents, maybe, or friends, or aunties, or Chinese neighbors, had sewn dolls for them, and painted on those dolls lovely, expressive faces.

The records of these children’s lives, and the objects that revealed their community’s devotion to them, inspired Lillia. And she let me ask, in as many and complicated ways as possible, the horrifying question of how families survive the chaos of war. Who loves us enough to keep us safe in the face of staggering danger and violence, and how can children come of age in circumstances as un-nurturing as those of occupied cities? How do we figure out how to live, to use languages both familiar and unfamiliar to tell stories that make our lives endurable? How do we read or imagine our ways back to hope, even when we feel the constant pulse of its twin force, dread?

And she let me ask, in as many and complicated ways as possible, the horrifying question of how families survive the chaos of war.

For the wartime Shanghai Jewish refugees, survival itself relied on numerous converging factors, ranging from complex glitches in passport control to acts of stunning heroism and self-sacrifice by human beings (Japanese consuls; unsung Chinese citizens; European parents and children willing to take astronomical risks on behalf of one another). It also required and inspired the creation of impressive amounts of art, music, and literature. Books played an essential part in their ability to build a community in which their children could grow up with an understanding that the world was a place elastic enough to contain both brutality and beauty.

Of course Lillia reads and reads. She is an artist herself, and makes puppets who convey some of the ways she understands both books and the world. In one such moment, she has her puppets speak like the characters in Gatsby, “who believed they had troubles but actually lived in luxurious America. Daisy, Jay, and Nick were free, such lucky puppets. I tucked them away, talking of parties, money, and love. They stayed safe under my cot while wind howled up Ward Road, our windows rattled and the river tantrumed: another flood. Tomorrow I’d make my puppets orphans from Oliver Twist. Like Wei and Ayli. I thought of the refrain of begging children in the streets: no mama no papa no whiskey soda. My puppets sang it. When I slept, I dreamt their stories, the show we would make for my mother when she arrived.” In this moment, Lillia goes from anger and envy to dread and reality, and from there, to hope. She does so by way of the books she’s reading, and the art they’re allowing her to make.

Naturally, this is partly a meta conversation; I couldn’t have made Someday We Will Fly (or my own characters/puppets!) without books, those I read in honor of this project, and also those available to me my entire life. Books have shaped my imagination and syntax, making me who I am as a writer and a person. Someday We Will Fly has a long bibliography at its end, because it’s important to me to be clear that what drives my novel is wonder. And that wonder leads me to other people’s books, and from there onto my own. This is historical fiction, so I don’t mean to simply wonder about “what happened,” but more profoundly about why people do what they do, and what that says about who we are and who we must be.

This is historical fiction, so I don’t mean to simply wonder about “what happened,” but more profoundly about why people do what they do, and what that says about who we are and who we must be.

There is so much reading that goes into writing, and it meant an inexpressible amount to me that so many people wrote careful accounts of the era I wanted to explore, in many cases the stories of their own and each other’s lives. The books in my bibliography are a testament to the kind of resilience that was my original inspiration. When I think of my own reading, I can’t help but feel the gratitude Lillia feels when Rebecca loans her books – for all the writers whose work sustained me, and also for Leo Zacharias. Because he had an inestimable fortune in those books he managed to carry to Shanghai, and he gave to as many others as he could the possibility of reading (and in some cases writing) their ways toward hope.

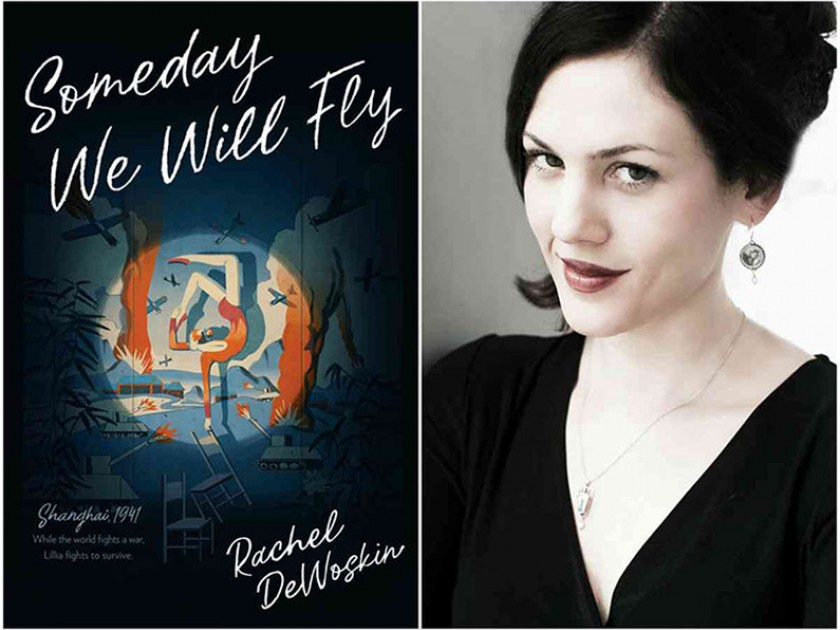

Rachel DeWoskin is the award-winning author of five novels: Banshee; Someday We Will Fly; Blind; Big Girl Small, and Repeat After Me; and the memoir Foreign Babes in Beijing, about the years she spent in Beijing as the unlikely star of a Chinese soap opera. Her poetry collection, Two Menus, was published by the University of Chicago Press in May of 2020, and she has Hollywood development deals for Foreign Babes in Beijing and Banshee. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and numerous journals and anthologies. She’s an Associate Professor of Practice at UChicago and an affiliated faculty member in Jewish and East Asian Studies.