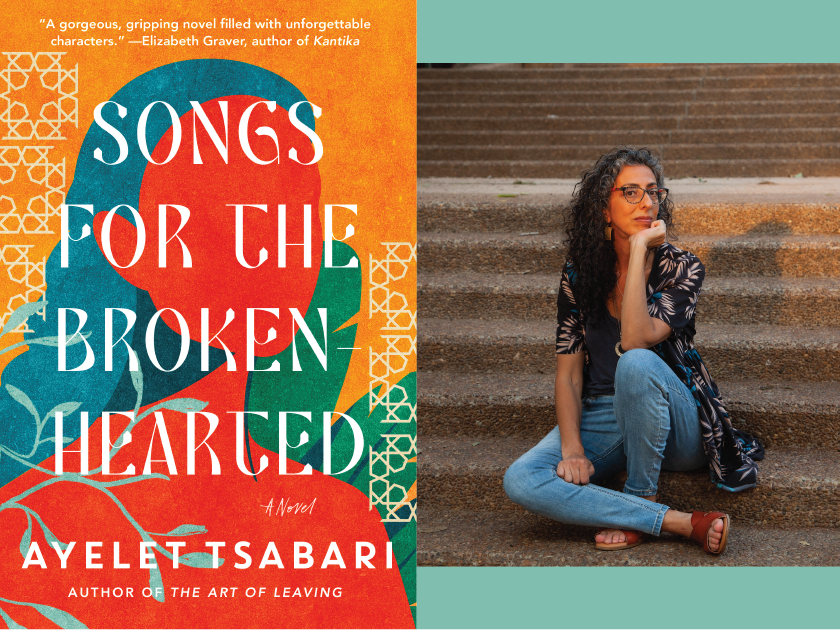

Author photo by Elsin Davidi

Ayelet Tsabari is intimately familiar with living between worlds. She grew up in Israel and lived abroad for many years. Her work often depicts the liminal experience of Yemini Jews in Israel. In her debut novel, Songs for the Brokenhearted, she depict the nuances of living as an expatriate and the search for belonging in and outside of one’s birthplace.

Seen from the perspectives of three protagonists, Songs for the Brokenhearted, is set against a backdrop of hope and political unrest in Israel during two different time periods. The novel begins in the 1950s, when Yaqub glimpses Saida for the first time in the migrant camp of Rosh Ha’ayin. We then flash forward to 1995. Zohara, Saida’s daughter, has returned from living abroad to mourn her mother’s death; Yoni, Zohara’s teenage nephew, feels his grandmother’s loss keenly and grapples with how to fill the space created by her absence.

Simona Zaretsky: Songs for the Brokenhearted is full of nuanced, multifaceted characters. How did you go about creating this cast? What drew you to the three narrators, and how did you approach threading their stories together?

Ayelet Tsabari: Saida and Zohara emerged in my mind long before I knew the plot or themes of this novel. I just knew them and loved them. Yaqub came later, in relation to Saida, and Yoni was the last to show up and was a bit of a surprise to me. Fiction writing isn’t interesting to me unless I make an effort to embody a point of view that is different from mine. I’ve watched countless videos of demonstrations against Yitzhak Rabin and the Oslo Accords and I suppose Yoni was born from my wish to understand how some people become radicalized.

I envisioned the book exactly as you said: voices from different generations and times in history interwoven to create a complex, multifaceted story of Yemeni Jewry. Especially because so little has been written about my community, I wanted the representation to be rich and layered and intricate. It was also important to me because this is a novel about voice and voicelessness. Through the different points of view of those around Saida, I was able to tell her story and give her a voice — and by proxy, give voice to our mothers and grandmothers whose voices were silenced and stories weren’t told.

SZ: The kidnapping of Rafael, Saida’s son, from the migrant camp of Rosh Ha’ayin looms over the whole novel. Society’s denial of these kidnappings and the government’s subsequent years of sidestepping and belittling of the subject seem to press on a wound unable to heal. Without proof of Rafael’s death, or life, there is just a question mark. This put me in mind of Zohara’s ruminations on her burgeoning Mizrahi awareness, when there is no representation in history texts or in popular culture: “You are left wordless, unable to narrate your own experiences.” How do you see this shifting in the novel?

AT: That question mark, that gap in the narrative, is something that characterizes much of our history as Yemeni Jews. In addition to the lack of representation in Israeli literature, there were few official records in Yemen. It was even more true for the women, since they were illiterate, and their stories were unwritten. In my own research into my family history (which I’ve written about in my memoir, The Art of Leaving) I’ve encountered many dead ends, gaps, and conflicting stories. My great grandmother’s grave, once I found it, was not even carved with her name. It was blank. If that’s not a metaphor for erasure I don’t know what is. At some point, I had to accept the limitations of research when it came to Yemeni history. That led me to question the authority of written history. Because who writes these history books? Who decides what to include in them? I had to shake the belief that written history mattered more than other types of narration. That some people’s history mattered more because it was documented.

My own way of countering the lack of recorded Yemeni Jewish history was to listen to Yemeni women and men, study their songs, and tell their stories. Zohara’s journey in the novel is similar. It is a journey of reclamation. And for someone like her, who comes from academia where everything needs to be cited and referenced, that’s a huge shift in perspective. She chooses to immerse herself in the rich oral traditions of her culture and accepts other forms of documentation and storytelling.

SZ: Zohara, Yaqub, and Yoni are all, in a sense, searching for a place and a country to belong in. Zohara attends an elite boarding school where she is othered for being Yemeni, and later moves to New York City to work on her doctorate. Wherever she lives, Zohara searches for connection and struggles to be fully seen. Could you speak about this quest for home across the characters’ journeys?

AT: My own sense of belonging has been fractured since childhood, partially because of my Yemeni heritage, partially because of losing my father when I was very young. Because of this, I find myself endlessly investigating the myriad reasons other people also struggle to find a sense of belonging. Yoni feels adjacent to the new family his mother has created and does not even feel entirely at home in his growing, teenage body. Zohara grew distant from her heritage, her neighborhood, and her family. Yaqub tries to reconcile the fantasy of the Holy Land he yearned for as a Yemeni Jew with the reality of Israel.

As an Israeli and a Jew, I’m interested in the idea of home not only on a personal level, but also on a historical level. The question of belonging in the novel is related to Mizrahi identity and to the wish — and often failure — to fit into an Israeli society that idealizes European, Ashkenazi culture. Nowadays, discussions about home in relation to this region have become flattened, one-dimensional, and combative, but the beauty of fiction is that it allows for nuance. If I had to characterize Jewish literature, I’d say that the search for belonging is a common thematic thread.

SZ: The novel is set primarily in Israel in the 1990s, with touchpoints in the 1950s. Do you see the novel as being in conversation with our current political moment?

AT: I set the bulk of the novel in the ’90s, during the fraught negotiations for the Oslo Accords and the assassination of Rabin, because it was a significant period for me as a young adult, and for all Israelis and Palestinians who lived through it/experienced it. It was a time when hope was palpable and peace felt possible. Rabin’s assassination was such a shock and a rupture. It was the first time that I remember feeling like history was unfolding in front of my eyes. We are living at a similar moment right now. Everything changed after October 7th. Obviously, the book was written prior to that, but I hope that it will provide some context and background to the current conflict.

SZ: The protagonist’s mother, Saida, is a poet; the narrator Yaqub a storyteller. In the novel, you describe how in traditional Yemeni culture men learn to read and understand Hebrew, whereas women do not. Their music and poetry is held in lower esteem. Could you discuss this hierarchy of language, and how it shifts as the community migrates to Israel?

AT: Certainly, the difference in the Yemeni men and women’s proficiency in Hebrew played a huge role in how they adjusted to Israel. The women had to learn the language from scratch, which deepened the inequality and further alienated the women from the rest of society. But as Bruria says in the novel, the move also afforded the women some freedom, by placing them around different ways of living. In Israel, women could work, study. I often tell the story of how my grandma, who was my grandfather’s second wife, used the move to Israel to pose an ultimatum to my grandfather to “get rid” of the first wife because she recognized that plural marriages weren’t acceptable here.

The gap in speaking Hebrew narrowed naturally over time. And as anyone who speaks more than one language can testify, we can be someone else, someone new, in a new language. It took longer for the gap in literacy to close. My own grandmother learned to read and write in her sixties, long after my grandfather passed.

My own way of countering the lack of recorded Yemeni Jewish history was to listen to Yemeni women and men, study their songs, and tell their stories.

SZ: Zohara wants to translate tapes of her mother singing, and there is also a metaphorical translation that the narrator endeavors to carry out as she moves from Ashkenazi spaces to Yemeni ones, from city to city or country to country, and across generations. Could you speak a bit about translation in all of its iterations?

AT: There were several acts of translation inherent in the writing of this novel. First was the act of translation that happened as I wrote; I am an author whose mother tongue is Hebrew, and who wrote a book in English about people who speak mostly Hebrew and Arabic. There is also a double translation in the case of the women’s songs that are included in the book — I relied on the translation from the original Arabic to Hebrew to create the English translation. I then made small changes and added my own lines to represent the dynamic character of the women’s songs, which historically, were changed slightly every time they were sung.

Which brings me to the translation from oral traditions into a literary work. By committing the sung poetry to the page, there’s a freezing that happens. The poetry stops being dynamic, and so, once again, an important characteristic of the oral traditions is scarified. When I honor our oral traditions by turning them into text, how do I maintain the integrity of the oral work? I tried to maintain that fluidity by having Saida rewrite parts of the songs. In doing so, I hoped to contribute to that tradition myself and play a role in passing it down.

SZ: Zohara’s narrative begins in grief. Returning to her place of birth in Israel to mourn the death of her mother. Zohara’s story, though, is steeped in layers of loss – the end of a marriage, the upending of perceptions about her mother, a reckoning with her own past behaviors, and many more deaths large and small. Could you speak about how loss operates in the novel?

AT: Loss is the inciting incident of the novel, it moves the story and the characters, who all react to it in different ways. The contrast between their ways of coping is also a source of tension, like Yoni and Zohara (one is being driven to radicalism, the other holds on to the dream of peace), Zohara and her sister, and so on.

I find that I often start my narratives in grief or loss. Perhaps because my own inciting incident was the death of my father when I was a child and it dramatically changed the course of my life. Similarly to Dahlia Ravikovitch (whose poetry Zohara was studying and is quoted in the novel), who often spoke and wrote about her own father’s death when she was six and the impact it made on her life. I often say that my fiction isn’t autobiographical (at least not in a straightforward way) but my themes are, and so, like belonging, grief and loss are themes I have been drawn to exploring and processing in my work, and I suppose I end up inflicting my characters with it.

SZ: The complexities of family are rendered so beautifully throughout the novel. Each narrator is forced to reconcile with the traditional family tropes that mainstream society imposes on them and to reflect on that. Present-day Zohara is faced with understanding her tumultuous relationship with her mother in a new light, seeing her as an individual, not just a parent. Could you speak on this shifting sense of perception?

AT: Mother – daughter relationships are fascinating to me as a writer, a daughter, and a mother to a girl. They can be so fraught and intense and intimate and wonderful. So often we are so self-centered as children that we can’t see our mothers beyond that role. For Zohara, this shift in perception happens in tragic circumstances. It’s the loss of her mother that leads her to see her anew. For me, the shift in perception regarding my own mother only happened when I became a mother. Motherhood allowed me to see her with clarity, compassion, and admiration, to recognize the person she once was — my grandmother too — before she married and had children. This was something I wanted to capture in this book and saw as a part of Zohara’s journey of reclamation.

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s managing editor of digital content and marketing. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.