Photo by Nina Subin

Magic, death, sex. These are the markers of great literature, or at least the kind of great literature that draws in readers by the bushel.

I didn’t come up with this trifecta. I learned it from a brilliant novelist who happens to be a great friend. She is greater than great, greater than best, a friend without whose constancy of generosity and warmth I would, in all probability, die. I am keenly aware of all that she does for me, never not grateful, and yet I still take her for granted. How could I not?

Like the friendships that buoy us in real life, the ones that appear in literature have a way of being brushed to the sidelines. Romances burn, marriages falter, families squabble, fortunes vanish, careers implode—these are the dramas that steal the story line. And so often friends remain secondary characters, waiting in the periphery, or drifting out from our watch altogether.

Maybe that’s why friendship remains such a mystery, still absent a dedicated rulebook after all of these centuries. “Love your neighbor,” the Torah teaches us, yet it can be quite challenging when your neighbor deals in micro-aggressions, or would rather hang out with another neighbor who lives in a townhouse on the other end of the block.

A friendship triangle is at the heart of my novel, How Could She, and none of the central characters is a paragon of platonic behavior. The women, each complicated and wonderful in her own flawed way, take notes and take stock, measuring themselves up against one another’s failures and successes. I like to think they’re simply still figuring things out, much like their author who gives herself a C‑plus in friendship.

Which is no doubt why I’m obsessed with it. Sure, I’ll take the death and sex, but it’s the platonic bonds, and all their inherent pleasures and pains, that have me in their grip. The stories contained in every single friendship are myriad, each relationship a funhouse mirror of different versions of the participants as they see both themselves and each other. Jewish literature, with its particular tradition of humor and sensitivity to feelings of yearning and exclusion, offers a diverse and deeply satisfying range of takes on the still under-served topic. Herewith, five Jewish authors’ depictions that are as delightful — and sometimes as frustrating — as friendship itself.

For me, it all started with Grace Paley, whose surprise appearance in the library of my Brooklyn high school set in motion my own dreams of becoming a writer. I remember sitting next to the window and staring at this white-haired woman whose unaffected speaking voice perfectly matched her plain, sometimes cantankerous, prose. Nearly two decades later, I would read a poem of hers, about an elderly couple sharing a park bench, at my wedding. Now in middle age, I maintain that every bookshelf, no matter how small, should contain her Collected Stories. “Friends,” originally published in 1975 in The New Yorker, is a gutting piece about three middle-aged women who visit their friend who is in bed, dying of cancer. Paley spares no punches: There are no miraculous recoveries here, only sullen teenagers and midlife aches and pains. Yet she infuses the piece with a sardonic hue that reminds us how our friendships can help make the worst challenges closer to something tolerable.

The fundamental challenge in the titular friendship in A Friend From England, by the English (and surprisingly, to me, Jewish) writer Anita Brookner, is the distance between Rachel and Heather. These two young women are thrown together by circumstance, as orphaned Rachel is close with Heather’s parents who hope that Rachel can serve as something of a role model. The pair spend countless hours in each others’ company, yet never manage to close the chasm. It’s a poignant, unsettling work that reminds us of the chemistry that is so essential to intimacy. Some bonds are simply not meant to form. For a more slippery slant, try Meg Wolitzer’s compulsively readable The Female Persuasion. It charts the tricky relationship between two women who start out as student and mentor and embark on a decade-plus long journey marked by ever-shifting power dynamics.

It is often said that the work of Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg, whose Jewish family was deeply entrenched in anti-Fascist circles, resembles Paley’s. They both wrote with a spare, wry style and it is impossible to read the prose of either woman and not feel as though she is serving wisdom by the tall glass. This is especially the case in Ginzburg’s deceptively slim nonfiction collection The Little Virtues, which is so frank and certain in its opinions that it reads as an essential guidebook to being alive. “Portrait of a Friend” is more monument than essay. In her melancholic rumination on the loss of another Turin-born writer, Cesare Pavese, she boils the memory of a brilliant and lonely man down to an everlasting essence, and exposes a side of him that is likely unfamiliar to scholars of his work. “He treated us, who were his friends, in a brusque way, and he did not overlook any of our faults; but if we were upset or ill he immediately became as solicitous as a mother,” she writes. Capturing everything from his few-fingered handshake to his habit of mistaking garish people he met at dinner parties for elegant creatures that might inspire future characters, she uses words perform a resurrection.

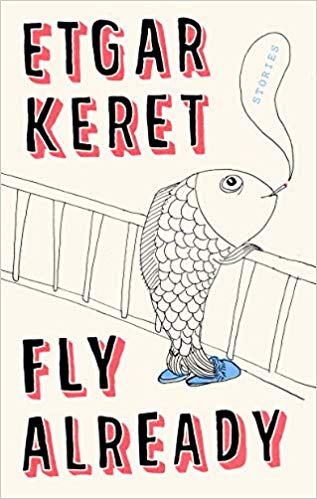

A totally different kind of vitality runs through the work of Tel Aviv-based writer Etgar Keret, who is a master of the kind of humor that is equal parts absurd and poignant. Book after book, his short stories delight with their off-the-charts zaniness and simultaneously tap into deep reservoirs of human pathos. This could not be truer in the case of “Todd,” a story in Keret’s newest collection Fly Already. It’s all there in the opening sentence: “My friend Todd wants me to write him a story that will help him get girls into bed.” Over the following pages, Keret describes a friend who is desperately lonely and needy in a way that will be familiar to anybody who has had an annoying friend. But Todd is also loyal, the kind of guy who “you know won’t jump into a lifeboat and leave you behind.” Todd looks up to his writer friend, and believes that his friend’s success and charm can be transferred as simply as a paycheck. The writer narrator gets to do his venting, to hilarious effect. And Todd gets his story, the one that will amuse and seduce. That both aims are achieved in seven pages is a reminder of one of the most mystifying and, come to think of it, magical facets of friendship: There’s never just one story.

Lauren Mechling is the author of several novels and a Senior Editor at The Guardian. Her work has appeared in Vogue, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, The Wall Street Journal, and The New York Times among other publications.