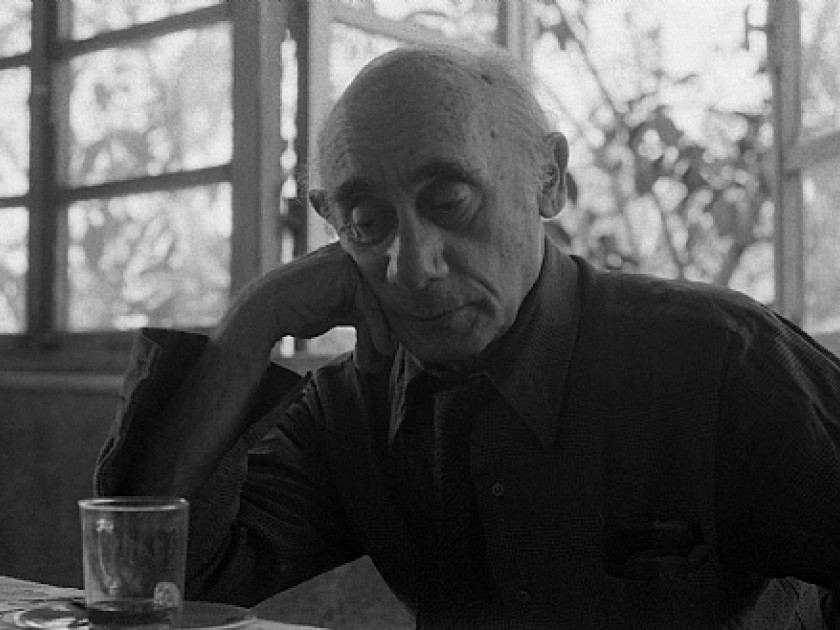

Life of Poetry: The Story of Avraham Halfi, image from the 2014 movie

I’ve been asked to write an essay about the difficulties of translating poetry but must confess it is not always difficult. You can take different approaches to line breaks and rhyme, but I think it’s fair to say that if you find rhyming challenging you probably should not translate poetry. Where then, lies the difficulty? Well, tone, perhaps. In some poets the tone appears very simple at first glance but when you start to translate them you realise that you do not really know for sure what they’re saying after all – the tone of the line is, on close examination, so elusive. Or there may just be one word that resists you because of cultural differences between the two languages, or perhaps because the context of that one word in that time and place makes it impossible to bring over. This last is not a difficulty unique to poets. The various translator lists I follow are awash with translators tearing out their hair about rendering some colloquial expression in a novel or play.

Many such difficulties feature in the work of Avraham Chalfi, who was born in Lodz, Poland, arrived in Palestine to work in construction and farming in 1924, joined the Ohel theatre troupe when it formed in 1925, and became a life member of the Cameri municipal theatre in 1953. Chalfi was known principally as an actor but also connected in the Tel Aviv literary scene as a man about town, author of over nine collections of poetry and, arguably most importantly, as the poetic “uncle” of the famous singer, Arik Einstein; he set Chalfi’s work to pop songs and sang it so compellingly that it entered the cultural language and was subsequently covered by a host of others musical groups. There are as many cover versions of Chalfi’s “Your Brow is Bound with Darkest Ore” since Einstein’s single of 1977 as there are of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” So when I am translating Chalfi I am approaching a very direct, impassioned form of speech, along with literary lines and language steeped in Jewish mysticism. The obvious meaning is not necessarily the only meaning, as in the poem below:

When Somebody Dreams of a Bird

A bird danced in my dream

Like any bird

That dances in a man’s dream.

When somebody dreams of a bird

That dances –

‘sing, my bird, miracles’ –

I would have wanted to ask her

From the beloved Bialik in “To the Bird”.

I remembered walking after him

As he passed in the street

Laden with mountains of knowledge.

Boy, have you got

A match?

He asked me once after midnight.

And after midnight it was the legend of the match that trembled.

When somebody dreams of a bird.

On the face of it this is a very simple poem. I happened to translate a collection of Hayim Nahman Bialik poems twenty years ago, so I was attracted by this scene of Chalfi encountering Bialik, considered the first major Hebrew poet of the modern era, a one-man revival of modern Hebrew writing in Tel Aviv. I loved the description of Bialik’s knowledge written on his face perhaps because Bialik’s major contribution outside of his own poetry was editing and publishing a new annotated compilation of the Talmudic legends, his one volume Book of the Legend making the stories previously accessible only through considerable labour in a dead language available and accessible in one book with very helpful notes that sold by the millions to a young Israeli audience who would have never opened a Talmud. That knowledge and the fame that came with it was, as Chalfi notes, a burden that weighed him down like mountains. But then there are problems you don’t immediately spot.

“To the Bird” is one of Bialik’s first famous poems and one I did not choose to translate because I found its metre too insistent. Many non-Israeli readers might not be familiar with the poem, so Chalfi’s casual allusion to the bird, and then the famous bird poem, might get lost. That line he quotes from Bialik is one I had to translate — on the gad — a line taken out of context. Imagine being asked to translate — ‘To be or not to be’ — not as a phrase in a line which is part of the most famous speech in English drama, but just like that — on its own. What can you do with such a phrase?

Then there was the second half of the poem which was much more concrete and, to be honest, the real reason I wanted to translate it in the first place. But there was one thing: the word Bialik uses to address Chalfi is in Hebrew ‘bachur’ — which is a lad, boychik, jungeman, whatever you like but has no an easy English equivalent that works in the twentieth or twenty-first century. So how should the great man address the (presumably younger) man but not teenager, because (presumably) the teenager would not be roaming the street at midnight? I opted for ‘Boy’ because there was seemingly no other option. But that one word was the only sticking point in the poem. There was the legend in the subsequent lines, another allusion to another famous Bialik poem, ‘To the Legend’ which addresses those very stories of the Talmud alluded to in his mountains of knowledge, but I hoped those lines would work in their surface meaning, without a reader’s having to know the allusion.

Imagine being asked to translate — ‘To be or not to be’ — not as a phrase in a line which is part of the most famous speech in English drama, but just like that — on its own.

Then there are complications of reception. Chalfi’s cultural footprint in Israeli life is considerably bigger than his status as a poet would suggest — it is as if Leonard Cohen’s poems had not been sung by himself but rather by Frank Sinatra. My problem became, in other poems which were indeed set to music, that it did not seem appropriate to translate the poem from the page, but rather, by listening to the song in various other versions, to capture the spirit of the musical setting as well as the lyric. To capture the frisson of the voice that breathed into the lyric, not just the line itself. It’s a fool’s errand, but I have been asked to translate Broadway lyrics before and it’s an entirely different level of difficulty from translating a moving little poem that touched you. Sometimes a boy is not just a boy but a man in a street, singing to the moon. And you have to write the moon into your translation, even if it isn’t in the poem.

This piece is a part of the Berru Poetry Series, which supports Jewish poetry and poets on PB Daily. JBC also awards the Berru Poetry Award in memory of Ruth and Bernie Weinflash as a part of the National Jewish Book Awards. Click here to see the 2019 winner of the prize. If you’re interested in participating in the series, please check out the guidelines here.

Atar Hadari’s Songs from Bialik: Selected Poems of H. N. Bialik (Syracuse University Press) was a finalist for the American Literary Translators’ Association Award and his Pen Translates award winning Lives of the Dead: Collected Poems of Hanoch Levin appeared from Arc Publications. He received rabbinic ordination from Rabbi Daniel Landes and a PhD in Theology from Liverpool Hope University for his study on Jewish commentators in William Tyndale’s translation of Deuteronomy and its revisions into the King James Bible.