Inner yard of a house in the Warsaw Ghetto, 2014

In the third week of July, 2019, we were in Poland: my husband, my son, my parents, my siblings, and the memories of three million murdered Jews. The Jews were everywhere: in the faint palimpsest of Yiddish lettering on Warsaw’s older buildings, in the empty treeless countryside, and of course in their desecrated graveyards. I got to Poland and surprised myself by wanting to sob. We were staying in a really nice hotel near Warsaw’s old town, and I got into the big clean bathtub and cried until my eyes stung.

“Well sure,” said Binnie, my old writing teacher, who had been to Poland and warned me what to expect. “Their ghosts are our ghosts.”

“I don’t believe in ghosts,” I said.

“That has nothing to do with it.”

My sister had brought us here on a Jewish heritage trip to better understand our family’s history. Our paternal great-grandparents emigrated from Warsaw in the late 1910’s and a maternal great-great-grandmother escaped Galicia in the 1890s. They had all gotten out while the getting was good, and thank heavens for that, because if they’d stayed much longer not only would I not be here but my son would not be here either. I try not to spend too much time meditating on the direction in which a butterfly once flapped its wings, but frankly it’s remarkable to me that any of us are here, especially any of us Jews. My great-grandparents – who could no more conceive of me than they could conceive of an iPhone – had the foresight to hand over the keys to the fish store and get on a boat to America so that my future parents could meet and have me and then my sister, who would take us back to Poland one day and put us up in luxury hotels.

While I cried in the bathtub, my son ate a pork chop at the hotel bar and my father drank a martini.

______

A Jewish heritage journey to Poland includes many stops, not all of which are depressing. The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, for instance, is dizzyingly comprehensive and beautifully arranged, located in the heart of what was Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto. It takes you on a path from the earliest Jewish settlements in Poland (sometime around 1000 AD), through the Middle Ages and up to the twentieth century, with displays on Yiddish theater, political action, and the recreation of a giant wooden synagogue. The audio guide is informative and charming. Also, if you’re into this sort of thing, (I am) the museum restaurant is outstanding.

What else does the Jewish tourist encounter on a heritage journey in Poland? Kazimierz Square in Krakow, full of stalls selling carved wooden Hasidim dancing to inaudible music; the Chmielnik synagogue; a few semi-restored cemeteries; the occasional klezmer concert; a van ride to Oświęcim, renamed Auschwitz by the Nazis after the 1939 invasion.

We went on a Thursday morning, all fourteen of us. The sky was dazzling, an almost unconscionable blue. We were quiet in the car, even the kids, and I looked out the window and tried to imagine the bloody fighting that had taken place on this ground eighty years before, but it was impossible. The day was so sunny and cool, and the kids in the car had begun singing “YMCA” along with the radio.

______

I had been warned of all sorts of things about Auschwitz: that it would be full of misbehaving tourists, that it would be too crowded, that it would be too stripped of context, that it would be too overwhelming to make it through the day. It was none of these things. It was, instead, exactly what I’d expected: well-preserved and vast and gutting. Wide open spaces pocked by train tracks and bunkers, watchtowers and outbuildings. Memorials. Tour guides. Ashen-faced visitors. You see as much as your imagination wants to fill in, and as a professional imaginer I saw it all – the stick-thin prisoners being marched in and out of the bunkers, the guards shaving the prisoners’ heads, the women relinquishing their shoes (they’re still there, behind glass, the piles of eyeglasses, suitcases, shoes). You see the Auschwitz prison – a hell inside a hell where captives were sent for “infractions” (taking an extra scrap of bread, not hustling fast enough to roll call). One punishment that still pops into my head at unpredictable moments is the tiny square of space where four prisoners were forced to stand all night, unable to move. Just standing next to each other, breathing, trying to stay awake, trying to fall asleep.

There is not even a remotely comforting or satisfying ending here. Most of the innocent prisoners were murdered; most of the guards and the staff escaped any punishment. The Polish government did hang Rudolf Hoss, the first commandant of Auschwitz, in 1947, but his fate is an anomaly. The gibbet is still there, not too far from the gas chamber.

______

We didn’t have to go into the gas chamber – it was allowed, perhaps even advised, to skip it if you were feeling faint or tired. But my son was full of eleven year old bravado and I didn’t want him to go in alone. So we walked into the small room, damp and dark, and stood there, and tried to imagine. But here even I, a professional imaginer, failed.

What would it have been like to hold your eleven year old’s hand and breathe your last breaths full of Zyklon B? To suffocate in this room? Squished in with hundreds of strangers, a dark windowless concrete bunker with showerheads streaming gas and the stinking terrifying smell of murder and the screaming? I squeezed Nate’s hand but he slipped away.

Nate?

I seemed to be alone, somehow, in the room. Everyone else had left. But then I felt a sharp tug on my ponytail.

Nate?

The tug again, even stronger. I whipped around.

Nobody was there.

I stood in the dusky room for another second, waiting for someone, anyone – waiting to feel the tug again or to hear my kid’s feet dashing out the door from some darkened corner, having successfully pranked me good. But I was utterly alone.

Around me, the air was perceptibly cooler.

______

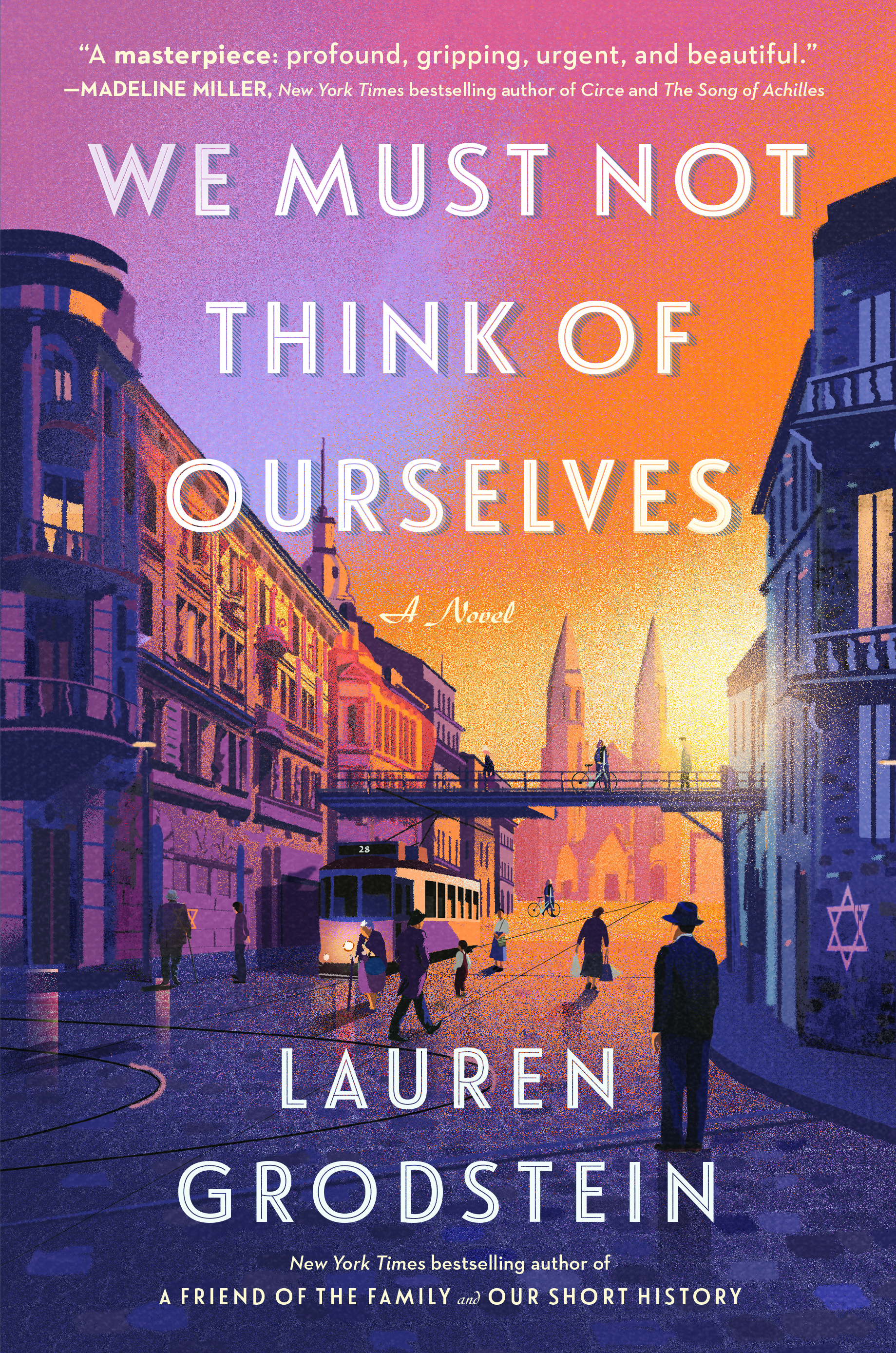

One of the ways in which the Holocaust is singular is in its numbers, but of course these massive numbers can blur the individual horror of each death. I wrote a novel about this time, We Must Not Think of Ourselves, to try to zero in on one man among the millions, to try to locate his terror, his confusion, and even his stolen moments of happiness in a time when the Nazis worked to take away, piece by piece, everything he counted on in his small, ordinary life. In my imagination, he was just one man, a little better in some ways than other people and a little worse in others, surviving the nightmare of the Warsaw Ghetto. He was not an everyman – he was uniquely and only himself. And it was his distinctiveness that he insisted on throughout the novel: this is who I am, this is what I do, I am not mere charnel for your slaughterhouse.

Unless, of course, he was.

Each novel I write becomes a bit of a game of what-would-I-do-if, but of each novel I’ve ever written, this was the one that felt most like a trap; every plot turn, a possible death. How to imagine a way out? Even with the endless stream of possibilities available to the fiction writer, how could there be any way out?

It took everything I had to find an honest and plausible path for my one Jewish man among the millions in Warsaw, 1941. I wrote this novel to honor the people like him: those who died, those who somehow escaped, and, most of all, the gas chamber’s ghost, whose tug I can still feel at the roots of my hair.

We Must Not Think of Ourselves by Lauren Grodstein

Lauren Grodstein is the author of Our Short History, The Washington Post Book of the Year The Explanation for Everything, and The New York Times bestselling A Friend of the Family, among other works. Her stories, essays, and articles have appeared in various literary magazines and anthologies, and have been translated into French, German, Chinese, and Italian, among other languages. Her work has also appeared in Elle, The New York Times, Refinery29, Salon.com, Barrelhouse, Post Road, and The Washington Post. She is a professor of English at Rutgers University-Camden, where she teaches in the MFA program in creative writing.