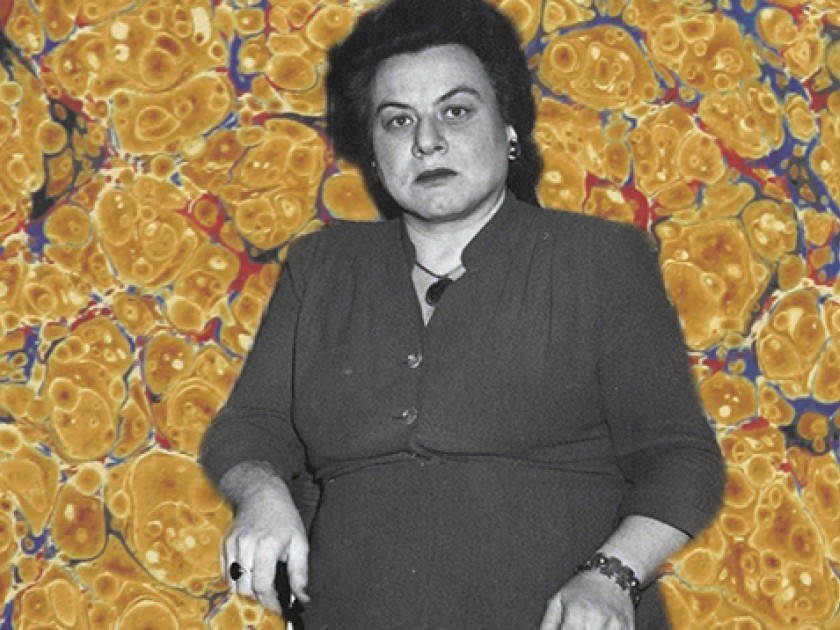

Photo: Courtesy of UNC Greensboro Special Collections and University Archives. Background: Courtesy of the British Library. Design: Natalie Aflalo

Twenty Notes on Muriel Rukeyser’s “To be Jew in the twentieth century”

1. It can be intimidating to read an iconic poem, because it appears with the sense of already having been read correctly, or better, more thoroughly, like moving into a house that the previous owners really knew how to handle. Which is why I’ll start with the first stanza of “To be Jew in the twentieth century,” rather than the whole thing:

To be a Jew in the twentieth century

Is to be offered a gift. If you refuse,

Wishing to be invisible, you choose

Death of the spirit, the stone insanity.

Accepting, take full life. Full agonies:

Your evening deep in labyrinthine blood

Of those who resist, fail, and resist; and God

Reduced to a hostage among hostages.

2. But this poem isn’t even a poem — it’s part of a poem. And one that has gone by many titles and been used for a variety of purposes. In the 1975 edition of Gates of Prayer, for example, it appears as “Israel’s Mission.”

3. The original title of “To be a Jew in the twentieth century” is “7.” At least, that’s how it’s labeled in Rukeyser’s fourth book, Beast in View (1944), part of a long poem titled “Letter to the Front.”

4. Rukeyser is a classic poet-visionary. But unlike your standard-issue visionary, Rukeyser’s vision is rooted in the brutal specificity of the here-and-now — even as it dares to see more, better, beyond … to the impossible. Like here, in the final lines of Part 2 in “Letter to the Front”: “I have seen a ship lying upon the water / Rise like a great bird, like a lifted promise.”

5. It would be against Rukeyser’s ethos to refrain from contextualizing “To be a Jew in the twentieth century,” or “7,” or whatever you want to call it. Rukeyser wasn’t about the “universal”; her poems take place—in specific years, locations, political and social settings.

6. So please allow me to contextualize. “To be a Jew” appears in Beast of View, alongside poems like “Bubble of Air,” in which Rukeyser evokes Walter Benjamin’s backward-facing, forward moving Angel of History:

The angel of the century

stood on the night and would be heard;

turned to my dreams of tears and sang:

Woman, American, and Jew,

three guardians watch over you,

three lions of heritage

resist the evil of your age

Woman, American, Jew: our poet.

7. To contextualize some more, “Letter to the Front,” container of “To be a Jew,” is a fascinating long poem in ten parts, including a wide variety of verse forms. Part I begins with another iconic Rukeyser line, “Women and poets see the truth arrive.”

8. But I’m on my eighth note already, and it’s time to home in on the poem/part-of-a-poem at hand.

9. “To be a Jew in the twentieth century” — there are many moves here that are characteristic of Rukeyser’s poetics:

10. E.g., a short sentence slicing up a line, like at the beginning of the second stanza, which we had better get to:

The gift is torment. Not alone the still

Torture, isolation; or torture of the flesh.

That may come also. But the accepting wish,

The whole and fertile spirit as guarantee

For every human freedom, suffering to be free,

Daring to live for the impossible.

With the choice it offers between refusing the gift of one’s Jewishness and accepting it,

the poem twists against itself, those short sentences breaking in two the lines in which

they appear.

11. And, e.g., the weird rhymes and the rhyme schemes that threaten to just disappear entirely. What does that soaring and surprising final word, “impossible,” rhyme with in this sonnet? The only reasonable candidate is “still,” as from the line “The gift is torment. Not alone the still.”

Still / impossible is the kind of rhyme that is sometimes called a near rhyme — as in close, but not exactly a rhyme. “Daring to live for the impossible”: Part of what makes the poem’s final line so soaring and surprising is how far that near rhyme is.

12. “To be a Jew in the twentieth century” is a sonnet, and a sonnet is a box. A sonnet doesn’t need to be about love, but in order to be a sonnet, it needs to be, on some level, about changing your mind. “To be a Jew in the twentieth century” is trapped in the box of itself, with two different options, exit and entrance, and that’s “torture.” It is strictly formal and “suffering to be free.”

13. My favorite part of the poem is the second half of the first stanza:

Accepting, take full life. Full agonies:

Your evening deep in labyrinthine blood

Of those who resist, fail, and resist; and God

Reduced to a hostage among hostages.

I love the line “Accepting, take full life. Full agonies:” After that relief, the acceptance of

full life, the agonies rise up immediately, promising terror.

The phrase “resist, fail, and resist” makes me think of another sonnet, John Donne’s holy sonnet “Batter my heart, three-person’d God” (probably not its “real” title, either): Come at me, God, Donne says (that’s a paraphrase), “That I may rise and stand, o’erthrow me, and bend / Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.”

A sonnet, like pain, or faith, twists and turns inside itself—against itself.

14. Setting aside questions of rhyme, meter, and length, why is “To be a Jew” — or “Batter my heart,” for that matter — a sonnet? Not because it’s about love. Because it turns.

15. In her essay “The Education of a Poet,” written shortly before her death, Rukeyser remembers her unique Jewish education, having grown up in a house with “no stories, no songs, no special food.” Rukeyser’s mother, however, told her

that we were descended from Akiba, the martyr who resisted the Romans in the 1st century and who was tortured to death after the Bar Kokhba rebellion was defeated. Akiba was flayed with iron rakes tearing his flesh until at the end he said, “I know I have loved God with all my heart and all my soul, and now I know that I love him with all my life.” Now this is an extraordinary gift to give a child.

So the first lines of this poem “To be a Jew in the twentieth century / Is to be offered a gift” are literal for the poet: Rukeyser was actually offered a direct sense of belonging within Jewish history, as a “gift.” I notice how many words from “To be a Jew” appear in this passage: torture, century, flesh, life …

16. Same story, different century.

17. The phrase “To be” is so twentieth century. People in the twenty-first century are hungry for books, movies, poems, songs, titled “How to be …” We want the answer along with the question. Just tell us what to do. Don’t let us struggle like a fish in a net, like opposing ideas in a sonnet, trapped in ambivalence.

18. There’s another interesting near rhyme in the poem: century/insanity:

To be a Jew in the twentieth century

Is to be offered a gift. If you refuse,

Wishing to be invisible, you choose

Death of the spirit, the stone insanity.

In that rhyme is the poem’s tension, its To be instead of How to be: the specificity, the ordering nature of time, this century and no other — rhymed with the chaos and randomness of insanity.

19. To set a poem in the twentieth century is a way of introducing politics into poetry. This isn’t just any time, a piece of deathless, timeless poetry; this is my now, wherever you, reader, may find it.

20. In the introduction to Florence Howe’s classic collection, No More Masks!: An Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Women Poets (which is dedicated to Rukeyser and named in homage to her “Poem as Mask”), Howe writes that Rukeyser’s poems are “about events and their meanings for Jews and others who live aware of a dangerous world.”

21. *(Bonus thought): Perhaps this sonnet is still standing in our imaginations and religious lives because “Twenty-first century” can be swapped in so neatly, from a metrical standpoint, for “Twentieth century.” It almost sounds better than the original:

To be a Jew in the twenty-first century

Is to be offered a gift …

This piece is a part of the Berru Poetry Series, which supports Jewish poetry and poets on PB Daily. JBC also awards the Berru Poetry Award in memory of Ruth and Bernie Weinflash as a part of the National Jewish Book Awards. Click here to see the 2019 winner of the prize. If you’re interested in participating in the series, please check out the guidelines here.

Lucy Biederman is an assistant professor of creative writing at Heidelberg University in Tiffin, Ohio. Her first book, The Walmart Book of the Dead, won the 2017 Vine Leaves Press Vignette Award.