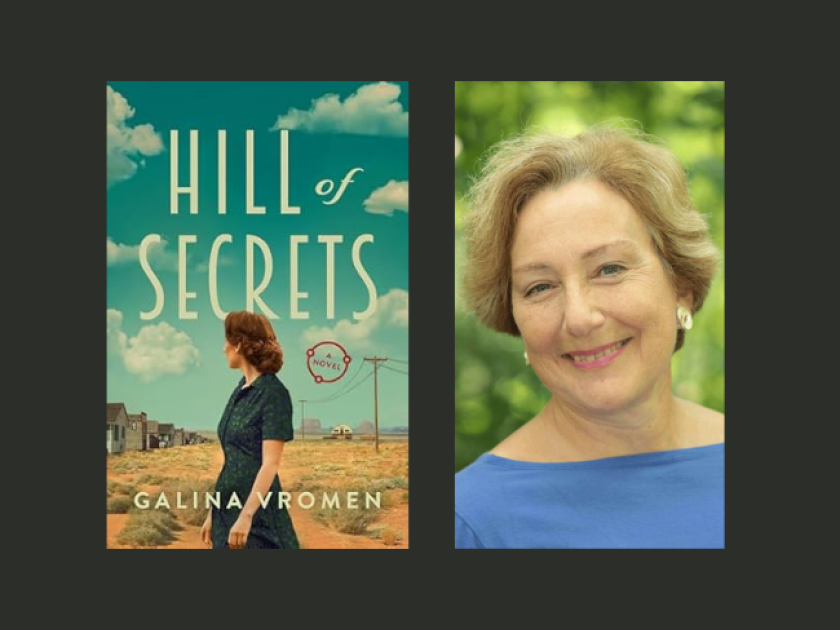

We live in an age that revels in revealing secrets — from using genetic-testing kits that may uncover half siblings, to unburdening ourselves to therapists, to being boldly honest on the internet. But is there value sometimes in keeping secrets? This is one of the central themes I explore in Hill of Secrets, a WWII novel set in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the world’s first atomic bomb was built — in secret. The novel follows five main characters living on the site who have their own personal secrets, even as they are wrapped up in this larger one. Some of these secrets corrode their relationships, while others protect them.

I raise the issue in my novel in part because of my own mixed feelings about secrets. So much good can come from honesty. And yet, I wonder if the penchant for telling-it-all sometimes carries a price that is too high, and causes unnecessary pain. With my novel, I want to prompt readers to weigh the value of secrecy and of disclosure.

My ambivalence about secrets led me to consider how Jewish theology and tradition view secrecy. It turns out that on the whole, Judaism looks favorably on it.

Let’s start with the name of the Almighty, YHVH. The pronunciation of YHVH itself is considered a closely guarded secret, to be revealed only to a select few. And the Almighty keeps secrets from us, which is why there is so much that we do not understand. At the same time, the Almighty knows all our secrets, so he is our confidante, keeping our secrets from others. In a similar vein, the Kabbalah is a secretive tradition, only to be shared gradually with the initiated, enhancing its power and authority. The Essenes, who inhabited the area around the Dead Sea in Roman times, treasured secrecy, their practices largely unknown to other Jews.

In Prophets, the telling of secrets is equated with gossiping or bad-mouthing (לָשׁוֹן הָרַע or lashon hara) and is therefore undesirable. “One who goes about as a gossip reveals a secret, but the faithful in spirit conceals a matter” (Proverbs 11:13). Rashi interpreted certain texts to indicate that if a scholar is asked intimate questions regarding his marital life, he need not answer truthfully.

Furthermore, in the Commentaries, even if the revelation of a secret is not gossip, one violates a person’s trust by revealing a secret. Rabbeinu Yonah writes in Sha’arei Teshuvah (3:225), “One is obligated to conceal a secret told him by his fellow even if there is no issue of tale mongering in revealing the secret.”

Only when secrecy causes harm to another does Judaism allow divulging a secret — but only after trying to convince the wrongdoer to confess on his/her own.

In Jewish history as well as tradition, keeping secrets has often been lifesaving. Consider baby Moses, Queen Esther, the Conversos during the Inquisition, or Jews hiding from the Nazis, to name just a few examples. There is power in secrets. They grant agency to persecuted Jews (and other persecuted minorities).

Secrets can also help preserve a community — for better or worse. Like in other religious institutions, sexual abuse and predatory behavior have sometimes been hidden by the Jewish community. In her book, Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, Letty Cotton Pogrebin explores the great fear of shame in Jewish families and the reluctance of the Jewish community to air its dirty laundry in public.

Elsewhere in Jewish literature, keeping secrets is sometimes for the best. To cite a few examples: In Philip Roth’s The Ghostwriter, Anne Frank lives in hiding in Vermont because she does not want to destroy the impact her diary has had on the world. In James McBride’s The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, good secrets abound, including helping to save a child from being institutionalized and withholding information about how the community obtains water for its synagogue. In Rachel Kadish’s The Weight of Ink, a scribe must hide that she is a woman in order to engage in her intellectual pursuits. In Ayelet Gundar-Goshen’s novel Waking Lions, an Eritrean woman keeps an Israeli doctor’s secret to blackmail him into providing other refugees with medical care.

In my own book, Hill of Secrets, there is a mix of secrets — some destructive, some positive. At one point, one of my heroines, Christine, muses that she “grew up believing that telling the truth was always good, however hard sometimes. But there was needless pain in truth. Sometimes deception was kindness … ” Another character, Sarah, finds relief in unburdening her secret.

In the end, perhaps it is best to be discerning about secrets, separating the self-serving ones from the self-preserving ones, and speaking out to prevent harm, but holding onto secrets whenever divulging them in the name of truth will cause nothing but pain.