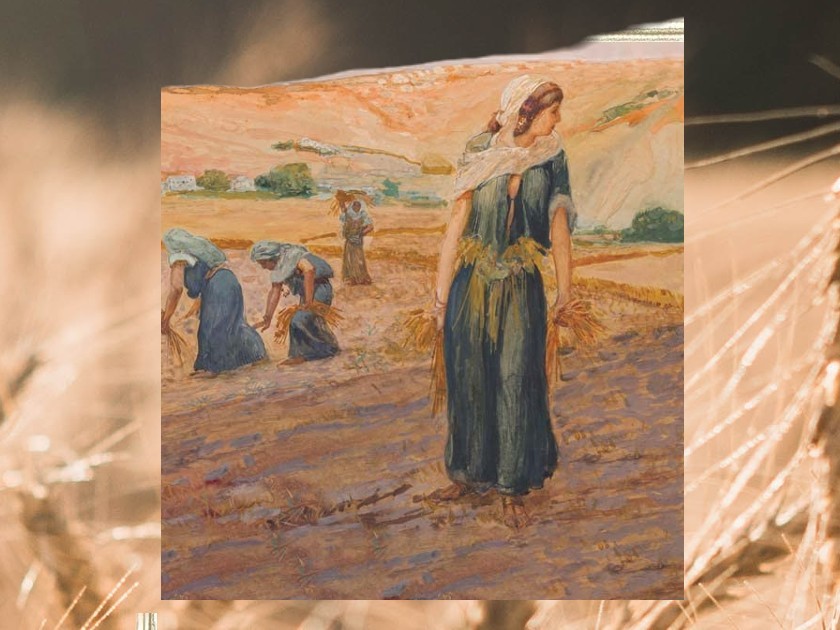

Artwork cropped from the cover of Ruth: A Migrant’s Tale by Ilana Pardes

If Ruth’s charm never seems to diminish, it is in part because of the rituals that commemorate her tale. The custom of reading the Book of Ruth during the Feast of Weeks, Shavuot, first emerged in a late phase of Rabbinic Judaism, in the period of the Geonim (between 589 and 1038 CE). We have no records of the rabbinic discussion regarding the decision to add the Book of Ruth to the holiday’s liturgical corpus, but the fact that Ruth’s tale takes place during the harvest season must have made it a compelling supplement to the celebration of a holiday that is defined in the Bible as a harvest feast (Exodus 34:22).

Within the rabbinic world, however, Shavuot is not only an agricultural holiday. It acquires additional significance as a feast that commemorates the giving of the Torah, matan Torah, at Mount Sinai. The rabbis deduced that the number of weeks that passed between the Exodus from Egypt and the event at Mount Sinai is equivalent to the number of weeks between Passover and Shavuot. But how is the Book of Ruth related to the giving of the Torah at Sinai? We can count on the rabbis to find several innovative connections. Two Talmudists, writing in the eleventh century, offer intriguing explanations. In Lekah Tov, Tobiah ben Eliezer calls attention to the centrality of hesed (loving-kindness) in both cases: “Why is this scroll read during Shavuot? Because this scroll is wholly devoted to hesed and the Torah is all about hesed … and was given on the holiday of Shavuot.” Simhah ben Samuel of Vitry explores another trajectory. In Machzor Vitry, he draws a comparison between Ruth’s tale and the story of the children of Israel at Sinai. Much like her, they undergo a ritual of conversion, as it were, when they accept God’s commandments and find shelter under divine wings. If the biblical law calls upon the Israelites to remember their past as gerim, as strangers in a strange land (Deuteronomy 24:18), Simhah ben Samuel of Vitry holds a mirror to his readers and invites them to regard themselves as Ruth and acknowledge the ways in which they too were converts of sorts, seeking a new beginning along an arduous road.

The relevance of Ruth’s life to Shavuot has been reinterpreted time and again over the centuries. Sixteenth-century kabbalists invented a new ritual – Tikkun Leil Shavuot, a night vigil of study. In their eyes, the giving of the Torah is inseparable from the wedding ceremony of the Shekhinah and her divine consort, which is why they feel the urge to provide the bride with the most refined adornments, tikkunim (the term tikkun in this context means adornment) as a present. What better decoration could they bestow upon the Shekhinah than a necklace of scriptural texts? They sit all night and link diverse verses – beads of sorts – from the three divisions of the Bible: Torah, Prophets, and Writings. Thanks to their efforts, the exilic rift in heaven vanishes momentarily as the divine lovers unite. And given that the kabbalists view Ruth as one of the embodiments of the Shekhinah, her tale is of utmost importance to the holiday.

What will the next chapters of Ruth’s exegetical history look like?

Another radical shift occurred some five hundred years later in the context of early Zionism. In Shavuot ceremonies of the kibbutzim, the agricultural significance of the holiday was restored and Ruth was set on a pedestal as a precursor of the Zionist woman pioneer. In the past two decades, we have witnessed another swerve in Israeli culture. Many cultural institutes in Israel, both secular and religious, hold study vigils throughout the evening and night of Shavuot. In this revisionary adaptation of Tikkun Leil Shavuot, Ruth’s tale has a place of honor. There are talks, or even sessions, on the Book of Ruth in almost every Tikkun of Shavuot. Many of these talks are devoted to questions of gender and migration or some kind of mixture of the two topics. In 2014, ALMA held a Tikkun titled “The Ger, the Stranger, and the Other” (ha-ger, ha-zar, ve-ha’aher), using the verse from Ruth 2:11 – “To come to a people that you did not know in time past” – as a subtitle. One of the panels called attention to the deplorable living conditions of refugees from Eritrea and Sudan in Tel Aviv while criticizing the Israeli government’s immigration policy.

This current trend is just as vibrant in the context of Ruth’s American reception. In the 1980s, Tikkun Leil Shavuot observances were held by liberal Jewish American communities with special attention to the question of social justice. In recent years, such Tikkunim have become more visible given that many Jewish communities across the US have adopted the custom. The embrace of Shavuot as a feast for activists is also evident on websites of Jewish American organizations. The website of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society is exemplary. Founded in 1881 to assist Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe, HIAS now seeks to provide aid to all who have fled persecution. Its blog for Shavuot calls for a reading of the Book of Ruth, as a tale that can teach us much “about welcoming the stranger” in our midst.

What will the next chapters of Ruth’s exegetical history look like? We can predict that Ruth’s migratory dimension will continue to be pivotal in future events of Shavuot. Migration is one of the most pressing problems of our time, with political implications we must reckon with daily. In recent decades, we have witnessed millions of migrants and refugees seeking shelter and sustenance in other countries. And disputes over immigration policies are among today’s most heated debates. But migration concerns us not only in the political sphere. It touches on our personal lives in profound ways. Many of us are either immigrants ourselves, children and grandchildren of immigrants, or some combination thereof. We can also assume that Ruth’s plight will continue to serve as a primary touchstone through which to explore the specificities of the experiences of women migrants. Alongside these more foreseeable adaptations, we can predict that, sooner or later, Ruth will emerge in another garb altogether, one that we can’t even begin to imagine at the moment.

Ilana Pardes is Katharine Cornell Professor of Comparative Literature and the director of the Center for Literary Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She is the author of Countertraditions in the Bible and The Song of Songs: A Biography.