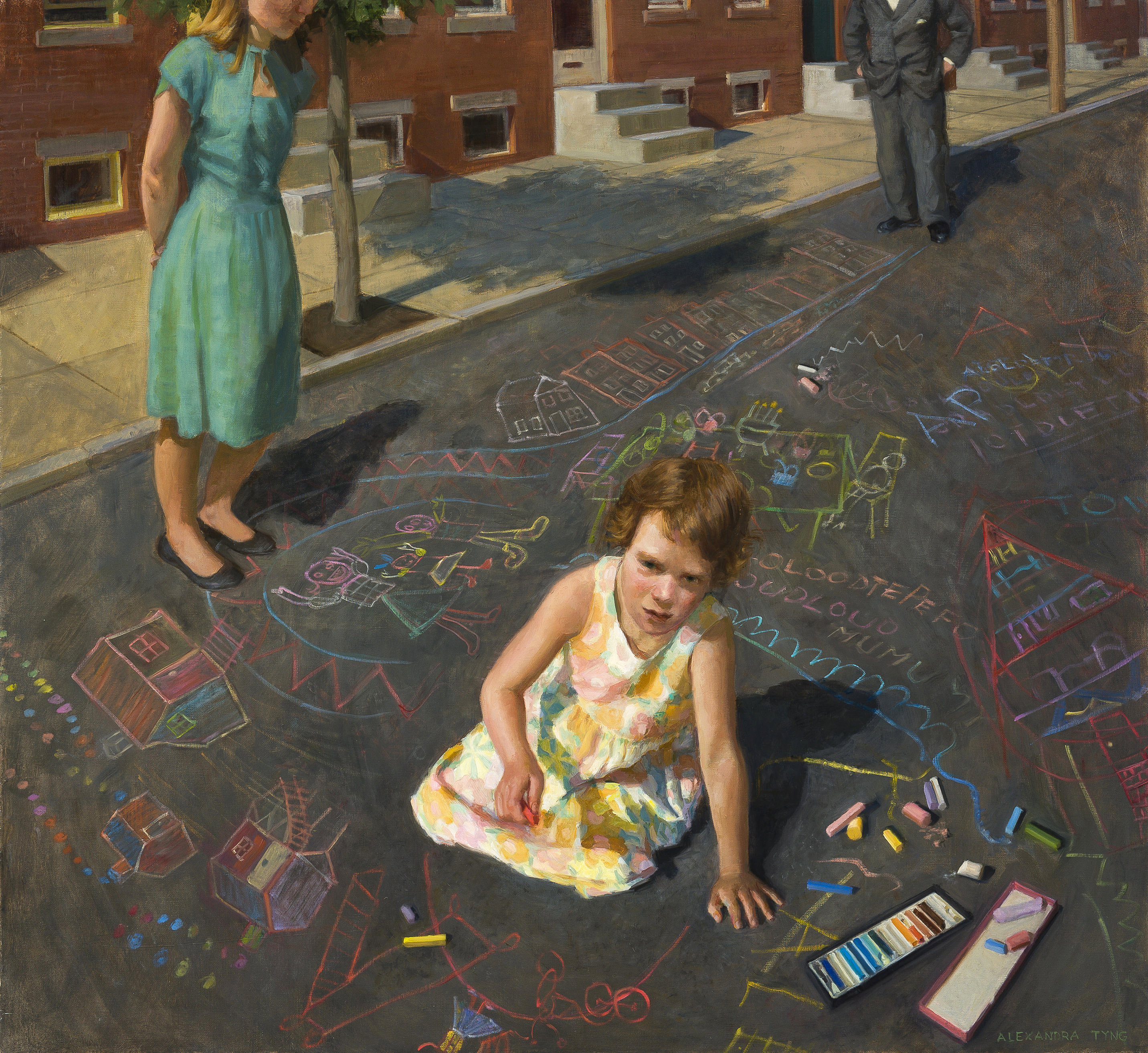

Alexandra Tyng, The Letter A, 2016, oil on linen, 42 x 46 in, detail. Reproduced with permission of the artist, courtesy Designers & Books.

This essay is excerpted from A Reader’s Guide to “The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn” © 2021 Designers & Books. The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn and accompanying Reader’s Guide are distributed by Yale University Press for Designers & Books and the Yale Center for British Art.

______

One of my clearest early childhood memories is of my father and me drawing side by side with oil pastels at the dining room table. He asked me what I wanted to draw and I said, “A castle!” and we both drew a castle. As our drawings developed, we talked about whether our castles should have one or more towers, or a drawbridge and a moat with water. Periodically I would look over to watch him and learn how he made things look three-dimensional. Two feelings stand out. One is our mutual delight in sharing an activity we both loved. The other is my trust in our family unit that came from sharing meals and often falling asleep at night knowing they were both there.

My father stopped visiting our house when I was five years old. I felt instinctively that our family unit no longer existed, but no explanation was given; perhaps because my parents weren’t married they felt it was unnecessary to mention that their relationship had ended. For the rest of my childhood, I saw him infrequently. My early trust in my father was replaced by a combination of love, insecure attachment, and anger. Lou’s feelings about me became more complex as I ceased to be readily affectionate toward him. He possibly felt a combination of love, guilt, and hope that I would need him less as he was involved in a new relationship and traveling.

Alexandra Tyng, The Letter A, 2016, oil on linen, 42 x 46 in. Reproduced with permission of the artist, courtesy Designers & Books.

The Letter A is about the inner life of children and the role creativity plays in their attempt to make sense of their lives. As a child of unmarried parents in the 1950s, I gradually realized that my family was not “typical.” I am drawing and writing in chalk on the street, describing the world as I understood it, while my parents stand by at different distances. The initial of my first name, A, appears many times in the chalk; an A is also stitched into the bodice of my mother’s dress as a reference to the particular dynamic between the three main characters in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s book The Scarlet Letter.

When we resumed seeing each other, our interactions were more intense. Secretly I wanted to run up to him and hug him, but my natural affection was stifled by knowing I couldn’t depend on him to be there for me. Even the prospect of seeing him caused internal conflict. Somehow in this difficult relationship we found that we could still connect through art and ideas. He would ask to see my drawings and look through them making appreciative sounds. I still have a stack of sketchbooks that he gave me beginning before I was two and continuing on into my teens.

They were real hardback books with black, pebbly-textured bindings and smooth white blank pages that I filled with colored-pencil drawings. As soon as I had finished a book, another would appear, and my mother kept track of my age at the start and finish of each. When I was old enough to walk downtown on my own, I would take the elevator up to my father’s office and we would walk together to Taw’s art supply store down the street. For several years I only wanted to draw in pencil and black ink, so Lou made sure I had crow-quill pens, India ink, and good paper. Sometimes his gifts seemed more like future investments — maybe because he was a little out of touch with where I was in my life — but I always appreciated the thought that went into them. When I was ten he gave me a polished wooden box that held an oil-painting set, but he was not around to show me how to mix colors, clean brushes, or even to explain that the box was supposed to rest on my lap. After a few disappointing tries, I put the box away and didn’t begin my first real oil painting until five years later. And while the paint box sat unused in my closet, Lou thought maybe I would like egg tempera, rummaged in his desk drawers through old dried-up tubes to see if any were usable, then finally gave up: “Let’s go to Taw’s and buy you some tempera. Not gouache, real egg tempera!” I took the tempera set to Maine that summer and discovered I enjoyed painting outside from observation. Lou was telling me it was time to work in color, and he was right.

If I wanted to see my father, I went to his office. I would watch his hands as he sketched a building in charcoal, adding shadows with strong parallel strokes, and foliage and people with a few curved, expressive gestures. These marks looked to me like the shapes that he made when signing his name, and I realized that drawing is rather like handwriting. I could almost see my father’s ideas take form as they traveled down from his mind through his arm and into his hand, emanating from his fingertips through graphite, charcoal, or pastel to make the thoughts into marks. Lou’s hands had solid, square palms and long fingers. When he handled a pencil or stick of charcoal, his movements were sensitive and sure, intentional yet playful. His strokes of varying pressure conveyed solidity or translucence; movement, eternity or ephemerality. My mother described his lines as “alive,” and she especially admired the way he drew trees. Even as a child, I knew she meant he drew trees as if they were growing, moving with the wind or reaching up to celebrate the light, and that this quality was more important than drawing every detail.

I’m not sure why Lou never showed me his pastel drawings, though he kept them in a desk drawer in his private office. I first saw one of his sketches of Albi Cathedral in the original edition of Notebooks and Drawings and I was fascinated by his helical “scribbles” of the towers. Even at eight years old, I realized he was drawing not what he saw but what he knew to be around the back of the cylindrical forms of Albi’s towers. Why had he broken the rules? It was not until I was older that I realized he was drawing to understand the form, to contemplate the possibilities of the hollow column that he subsequently explored in designs for the Bryn Mawr Dormitories, Mikveh Israel Synagogue, Hurva Synagogue, Indian Institute of Management, and Capitol Complex at Dhaka.

During our occasional conversations, I loved listening to Lou talk about “Silence and Light,” his idea of how works of art are created from “spent light” and exist on a threshold between the measurable means and the “unmeasurable” desire to be. In the last decade of his life, Lou designed buildings that emanated energy and inspired wonder. What gives certain buildings these qualities that could be felt but not measured? Lou pondered this question repeatedly over many years as he stood in ancient spaces like the Pantheon and modern spaces like Ronchamp. Measurable qualities like pleasing proportion and relationships of elements are important in the design of a building, but the intangible ingredient, the energy emanating from the space, is elusive. Lou stood in many buildings marveling at this energy and taking it in. Through this process, he was eventually able to envision, draw, and design buildings that, when finally built, belonged in the liminal space between Silence and Light.

Alexandra Tyng, Art and Legacy, 2012, oil on linen, 40 x 52 in. Reproduced with permission of the artist, courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery.

In Art and Legacy, I address the contrast between the artist’s consuming drive to create something enduring, and the creative or material legacy that is left after the artist’s life is over. My father sits in a tower, isolated, focused on painting a watercolor, while his three children watch. Each of us sees him through a different window or perspective. But the windows are also barriers because we children cannot reach our father or even see him clearly. While painting this I was also thinking about my relationship to my own children.

In college I regularly visited the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston where I inevitably gravitated to an oil painting that took up most of one wall: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit by John Singer Sargent. Everything about the painting fascinated me. I soaked up lessons on edges and brushstrokes and color, but I could not figure out how Sargent had created large areas of darkness that were mysterious, transparent, spacious, and full of air. All I could do was stare at the darkness, wondering how paint could have created this transformative illusion. No matter how long I stared at the painting the answer eluded me. Perhaps this was how Lou felt when he stood inside the great architectural masterpieces and felt but could not define what made them great.

My father died when I was nineteen and a junior in college. I had been on the verge of asking him some difficult questions, and part of my grieving process involved accepting that I would never hear his response and would have to accept the lack of closure. I read everything I could find that he had written or spoken, and the following year I wrote my senior thesis on his philosophy of architecture and life. In the process of learning more about how his mind worked, I was especially intrigued by his drawings of concepts like “The Room” and “Silence and Light.” They were poems of interwoven pictorial and verbal language. At that time the art world was focused on abstract conceptualism, so the idea that representational art could also be “conceptual” did not occur to me until that time. I knew I would be an artist.

In this way and in other ways, Lou was still communicating with me through art after his death. Right after college, I began painting seriously, but I wanted to transition from simply recording what I saw to understanding the color relationships generated by nature. In Lou’s words, “We only know the world as it is evoked by light.” One of Lou’s pastels hung on the wall of my mother’s workroom, and I wondered why he had made the shadows red when the light was yellow. Shouldn’t the shadow color be complementary to the light? But one winter day I noticed that the snow appeared golden in direct light, orange with a violet tinge in oblique light, and ultramarine blue in shadow. The color of the direct light on the snow was clearly not complementary to the color of the shadow; instead, the areas hit by indirect light were complementary to the shadow. In my paintings I began to approach color systematically by first considering the color of the direct light and then choosing the colors generated by it, mixing them with local colors and adding reflected light. In this way I unified the color relationships in my work. In 1991, when Jan Hochstim’s Paintings and Sketches of Louis I. Kahn was published, I saw the vast majority of Lou’s pastel drawings for the first time. Because Lou worked in pastel, his distinct marks of complementary colors were visible in the halftones and shadows. I was beyond excited to see that, in drawing after drawing, he created color schemes by using the same kind of three-color relationships I was using to indicate the time of day and to “turn” form from light to shadow, thus creating the illusion of three dimensions.

In the past fifteen or so years, I have returned to a very early love of mine, narrative figure painting, and I have found it to be challenging technically in a fun way, and even more challenging in a torturous but rewarding way as a vehicle for communicating ideas. More than anything, I wanted to paint my family, especially my father, but I hesitated. After spending my childhood feeling as though I had to stay “in the shadows” and not acknowledge our relationship out in the world, I was still holding back. Finally I realized, “This is my story; it belongs to me; I’m giving myself permission to tell it,” and I began a series of multi-figure paintings of various family members interacting in environments. The scenes are constructed from my imagination but they are based on actual situations and experiences. As I am painting, I feel as though I’m illuminating problems and creating possibilities for positive resolutions.

Alexandra Tyng, Scavengers, 2019, oil on linen, 60 x 60 in. Reproduced with permission of the artist, courtesy Dowling Walsh Gallery.

Scavengers is my visual description of how it feels to have our boundaries invaded. The idea first came into my mind after a biography of my father was published and his personal life was revealed to the public, discussed, and judged. My siblings and I each had different reactions, which I exaggerated for dramatic effect in the composition. The seagulls are an obvious nod to Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, one of my favorite films. My goal was a combination of horror and humor.

The idea expanded to include the problem we are all dealing with today: an invasion of privacy on many levels and in numerous ways, including data stealing and sharing on social media,internet, and cell phones. The walls that we thought were solid have simply dissolved, leaving us anxious and vulnerable.

One of my most important goals is to not only tell my own story, but also to tell a story that resonates with others. I am constantly asking myself, “What is this painting really about?” while continuing to dig deeper and reach farther for meaning. When people tell me my figure paintings are communicating something that is felt but not seen, I think of the elusive quality of Sargent’s darkness, and of the dynamic threshold between Silence and Light, and I feel hopeful that I might somehow be able to communicate my personal emotions, challenges, realizations, and visions not just as “Alex’s experiences,” but as human experiences. The Letter A is a self-portrait of me at age five, making sense of my world, but it is not just about me, because we all go through our journeys of self-discovery.

Lou was not the kind of father I could rely on to be there when I needed him, but I never doubted that he loved me and supported me in other ways. He suppressed my public voice by not openly acknowledging my relationship to him, but he encouraged my private, personal voice through art-making. He gave me the sense that art was a worthy challenge, and that I was capable of taking up the challenge. It was up to me to find my voice out in the world and use it well.

Alexandra Tyng is an award-winning figure and landscape painter. Her work has been exhibited worldwide and her portrait of her father, Louis I. Kahn, is in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. She is the author of Beginnings: Louis I. Kahn’s Philosophy of Architecture.