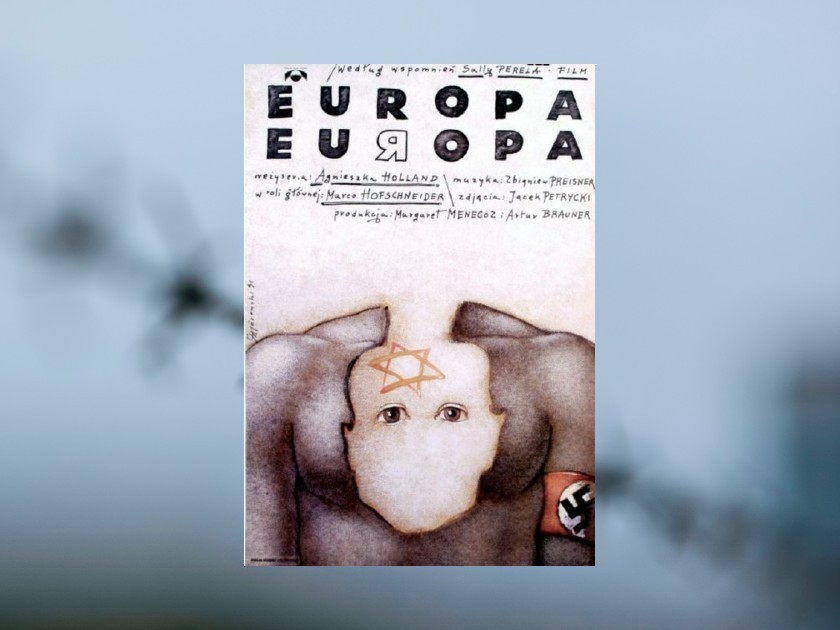

Europa, Europa, Polish Movie Poster, Designed by Mieczyslaw Gorowski

I thought about imitation and reality while writing my historical novel, The Girl Who Counted Numbers. In the book, Susan, a seventeen-year-old New Yorker, is sent to Israel by her father to try to find what happened to his brother during the Holocaust. Although the story is fictional, I wanted to make the settings and situations as authentic as possible. I spent several years reading and researching interwar Eastern Europe and life during the Holocaust before I started to write. Still, l felt uneasy about one thing: my portrayal of Susan’s uncle. As the book’s mystery unfolds, we learn that he survived the war by posing as a Nazi. I was unsure that such a thing could have actually happened and worried that I might be criticized for making it up.

Somehow I missed the incredible, true story of Solomon Perel: a Jew who posed as a Nazi in order to survive the Holocaust. Perel didn’t simply have a false name or papers; he was immersed in his false identity. As a young boy, Perel moved with his family from Peine, Germany to Lodz, Poland. When the Nazis invaded Poland, they were forced into the ghetto. Perel and his brother fled Lodz to the Soviet Union where he lived in an orphanage. In June of 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, he left the orphanage but was captured by the Nazis. Determined to save his life, Perel buried his identity papers and when asked if he was a Jew, he said that he was an ethnic German. He became a front line German-Russian translator and then joined the Hitler Youth. He later wrote in his memoir, Ich war Hitlerjunge Salomon, “that my mental faculties were so befogged that no ray of reality could penetrate. I continued to feel just like one of them.” The book was later translated into English, French, and German, and was made into a German language movie, all of which were titled Europa Europa.

Throughout his senior years in Israel, Perel lectured on tolerance, but there were many people who said that he “never fully purged himself of the Nazi identity he had adopted.” In 1992, Perel told The Washington Post that he had “a tangle of two souls in one body.”

Somehow I missed the incredible, true story of Solomon Perel: a Jew who posed as a Nazi in order to survive the Holocaust.

I first heard of Perel months after my book came out, when The New York Times reported his death at the age of ninety-seven. I was fascinated to read about Perel’s story as it validated the possibility that a Jew could have actually passed as a Nazi and somehow survive with such a dual identity.

The real question is — Is it important for a fictional work to have a basis in real life? Not necessarily. Writers often can invent characters who have never existed and whose actions are surprising and unexpected. Science fiction books, for example, often are built around imaginary beings. More often, though, fictional works lean on people (singular or plural) who have lived somewhere, people who the novelist transforms into new characters, incorporating bits and pieces of the old character and creating new landscapes, and new experiences. In a historical novel, it is especially important that characters, singular or composite, real or imagined, be believable.

Set in 1961, with the Adolf Eichmann trial in the background, The Girl Who Counted Numbers unravels the many secrets that pervaded life in the concentration camp. Friends who were enemies and enemies who were friends. Germans who did favors for Jews and Jews who did favors for Germans. Life in the camps was brutal, but between the extremes of black and white, there was some gray. A rape that turned into a love affair, leaving a woman who for the rest of her life loved and hated herself. An illegal, forbidden, and passionate love affair between two men that lasts for years. A woman who could never quite resolve her identity. Secrets that helped people endure the suffering of living in the camps, pain and anguish, their conflicting identities somehow surviving.

Roslyn Bernstein has been a storyteller all her life, sometimes working for a true account in the narrow sense as a journalist when it’s reporting or history, and sometimes in a wider, more resonant sense when composing poetry, short stories, or a novel. As a journalist, she has reported in-depth cultural stories for venues including Guernica, Tablet, Arterritory, and Huffington Post. Sixty of her online pieces were reprinted in an anthology, Engaging Art: Essays and Interviews From Around the Globe. While reporting on all forms of art and architecture, documentary photography has been a major subject of Bernstein’s writing and teaching since the 1970s.She is the author of a collection of linked fictional tales, Boardwalk Stories, set in a seaside community during the 1950s, and the co-author with Shael Shapiro of Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo, which focuses on one building to tell the story of SoHo’s transformation from a manufacturing district to a live-work arts community. For most of her career, she taught journalism and creative writing at Baruch College, CUNY where she was the founding director of The Sidney Harman Writer-in-Residence Program. The Girl Who Counted Numbers was inspired by the seven months that Roslyn Bernstein spent in Jerusalem in 1961. She has tried to be attentive to historical details although the story of Susan Reich, her family, and friends is fictional.