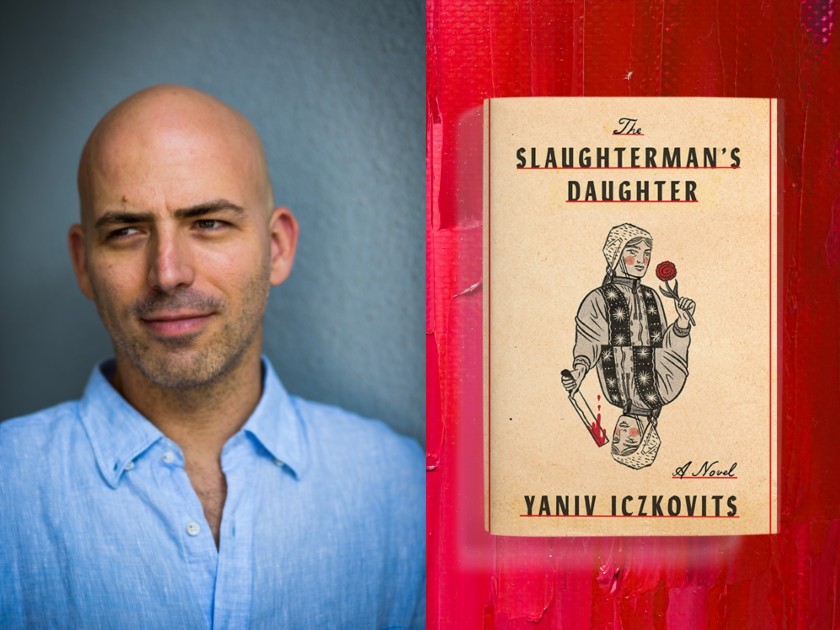

Photograph of Yaniv Iczkovits by Eric Sultan

Tipping its streimel to the likes of Sholem Aleichem and I. L. Peretz, The Slaughterman’s Daughter could almost be mistaken for a lost Yiddish classic. Hilarious, wise, and frenetic, this novel by Israeli author Yaniv Iczkovits harkens back to a bygone era while bringing a thoroughly modern sensibility informed by the likes of the Coen Brothers and Quentin Tarantino.

At the heart of the novel lies Fanny Keismann, the daughter of the local shochet, who sets off from the small town of Motal to hunt down her sister’s wayward husband. She doesn’t get far before a gang of brigands, sensing easy prey, set upon her. With her trusty knife, Fanny makes short work of them and continues on her way, leaving the local authorities stumped. What follows is a brilliantly madcap game of cat and mouse, involving the Russian Army, the Tsar’s secret police, all manner of eccentrics and ingrates, and one very jovial chazzan.

Epic in scope and rich in execution, The Slaughterman’s Daughter is a contemporary Jewish masterpiece. Little surprise that it recently won the highly prestigious Wingate Prize, and previously won both the Ramat Gan and Agnon prizes. It was also shortlisted for Israel’s premier literary award, the Sapir Prize.

Bram Presser: What does the modern lens bring to a story like this? I’m thinking particularly of your knowledge of what came after for the people and communities that once thrived in the Pale of Settlement.

Yaniv Iczkovits: I think that this question is extremely important, because it informed my entire motivation for writing this book. After all, when the great nineteenth-century Yiddish writers wrote, they depicted the present, their present. They didn’t know what was going to happen to the people like those they wrote about. But I wrote about them in retrospect, knowing the horrible fate that would await them. To what end?

I believe that my modern-day perspective is essential to the novel in two respects: first, I wanted to bring those forgotten memories and characters of a lost world — an entire sphere that has been completely demolished — into the present. I wanted to show the richness of a culture that is now gone but is still a major part of who we are, or at least of who I am. Growing up in Israel, you learn a lot about the history of Jewish life, and the awful stories always take over. But since my family came from Eastern Europe, I also heard a lot of interesting stories about Jewish life before World War II. Some of them were quite funny; other anecdotes were colorful and intriguing. I started to ask myself: what do I actually know about Jewish life of the past? What was the daily routine? I wanted to go deeper into this lost world that nobody talks about. I felt that it is important for us to realize how different each person was from one another, each one a world in themself: one person devoutly Orthodox, another a secular Zionist; one a sportsman, another a baker. They went to different synagogues and followed different rabbis. It’s just a shame that all we remember from them is their horrible fate.

Second, such a story will inevitably raise poignant questions for a present-day reader, and I like poignant questions. For example, has much really changed since then? Just to give a short example (but obviously there are many more): the miserable status of aguna [a married woman whose husband refuses to grant a Jewish divorce, thereby preventing her from remarrying] still exists nowadays and a lot of women are suffering from being controlled by these laws. In fact, Fanny’s journey could easily happen in contemporary circumstances, so I advise all those wayward husbands to be aware! And on a different note, do we, in Israel, treat minorities with the same grace with which we wish other nations would treat us?

BP: Readers of classic Yiddish and Russian literature will feel right at home in Motal and its surroundings, but they will never have encountered a character like Fanny Keismann. What drew you to writing such a strongly feminist take on those literary traditions, and how does Fanny’s quest to find her sister’s wayward husband both build on and challenge what has come before?

YI: From the outset, it was pretty clear to me that the protagonist should be a woman. It was important for me that Fanny would be active, respond to injustices, and yes, sometimes be violent. I couldn’t even imagine a man taking on such a mission. The world of men has been a bit lazy in changing rules that are convenient to them. But I think that not only Fanny, but also the rest of the characters as well — men or women — are really struggling to move, even one inch, from the harsh dictates of society. Take Zizek for example, who was a soldier in the Russian empire for so many years. When he retired, he should have gone to Minsk, bought a house, settled down, and that’s it. But no, he went to his family’s shtetl, where everyone wanted to forget about him, and settled by the river, so that everyone would be distressed by his appearance. Today, if you want to be a humanist, you cannot simply do it in a comfortable way. You have to resist, and sometimes even fight for it.

What is funny about Fanny is that most of the other characters don’t expect her to be the source of all these “disturbances.” They expect her to be gentle and to stay at home, like most Jewish women in nineteenth-century Eastern Europe. And when they become familiar with her character, they don’t know how to frame her. She is “un-frameable”, as I believe most people are. When you don’t know how to frame someone, that is when you have no choice but to recognize the complexity of human life.

BP:The Slaughterman’s Daughter is also playful and experimental in ways that the classics are not. It engages with very modern literary traditions. I’ve heard you mention Tarantino as a reference point, and there is no question about the cinematic air of the novel. What did postwar literature and more modern forms of media bring to the writing of this novel?

YI: The hardest thing about writing this book was finding the correct language. I didn’t want to imitate the great Yiddish writers of the nineteenth century, and I didn’t want to write in a contemporary style. So I had to do a lot of experiments, playing with the sentences and the form, until I felt that I’d reached a rhythm that is a bit playful, with a touch of Yiddish, but also a touch of modern American references such as Cormac McCarthy, Tarantino, and the Coen brothers. I guess I was looking for a way to meld the old with the new, and in this sense I allowed myself to be influenced by cinema and television. I later realized that when we are in the shtetl the language is closer to Shalom Aleichem’s or Isaac Bashevis Singer’s and when Fanny arrives at a military camp the language echoes some of Isaac Babel’s writings, and when the robbers appear we are caught in a Tarantino scene. Sometimes I didn’t write for four months because I couldn’t find the right language for a certain character, but it was clear to me that the book had to be grounded in an interplay between the old and the new, the literary and the cinematic, the heavy and the humorous.

Literature invites us to tell ourselves a different story to the one we are used to. While the forces of reality usually tempt us to justify our views and actions, literature and imagination demand a different response.

In general, my view is that literature cannot ignore the global trends and the modern forms of media. That doesn’t mean, of course, that books should be written like a TV series. We have to remember that the visual form will always win the first battle. But literature is not about winning battles. It’s not about shouting for attention. There is a very nice phrase by Wittgenstein that says that in philosophy the winner is the one who finishes last. I think that something similar can be said about literature. But coming in last only means that you are already aware of other forms of media and can contain them. Therefore, you can discuss them, play with them, echo them — and not only them but with the history of literature itself. For example, when the Russian greats wrote about Jewish characters they always depicted them in a stereotypic way, and when the Yiddish greats wrote about the local Russian or Polish people they also failed to overcome those typecasts. This is why Novak, the secret police officer, was very important for me. I wanted to correct these failures in my book. Do a tikkun. Novak is transformed throughout the novel. Eventually he dresses like a Jewish Hasidic and gets carried away in a “Tish.”

BP: There seems to be a philosophical battle at the heart of The Slaughterman’s Daughter; a battle of best intentions. Almost every character is driven by a desire to do right, to make things better. And yet they are fundamentally at odds. I was interested to learn that the translation of the Hebrew title is “Tikkun after Midnight.”. What role does tikkun play in the novel and how can these competing “good intentions” be reconciled?

YI: Tikkun olam is an ancient Hebrew term that basically means “correcting the world” or “world repair,” which can be achieved by obeying certain religious rules. But it also has a personal meaning — something like “correcting” or “repairing” oneself. Correction always requires good intentions, but these will not be enough if you are not willing to transcend your personal limitations and boundaries, and those of your community. Therefore, tikkun truly requires you to step out of yourself and become aware of other intentions.

And this, by the way, is the ultimate power of literature. Literature invites us to tell ourselves a different story to the one we are used to. While the forces of reality usually tempt us to justify our views and actions, literature and imagination demand a different response. Each of the characters is challenging other characters to see dimensions of reality that, until now, they were blind to. But the resistance to these new perspectives is not easy to break, and this is why everything goes wrong for everyone in this novel.

BP: Does fate or serendipity also play into that? After all, it is Fanny and Zizek’s chance encounter with the robbers that brings them to the attention of the Tsar’s police. Some characters seem to be the products of happenstance in their early lives, while others are the authors of their own fates.

YI: Well, there is always an interplay between fate and chance, and there is a question as to how much of Fanny and Zizek’s encounters are not predicted. When a Jewish woman sets out into such a wild journey, she can assume it won’t go unnoticed. And I really believe that Fanny knows that she is going to use that knife. Adamski also knows that any encounter with his old friend Zizek will lead to trouble, especially since Zizek is wanted by the secret police. So I think that although it might seem as if a lot of events happen by chance, the characters enter into them with open eyes.

BP: I thoroughly enjoyed the interplay of doctrine and dogma — both political and religious — that is woven throughout The Slaughterman’s Daughter. How important are “the rules” versus the compulsion, or even the necessity, to break them?

YI: That is honestly the main question in the novel, and it’s not only a political or religious question, but also a personal one. Two of the most prominent thinkers of recent times, Freud and Kafka, grew up with dominant fathers and strict rules. But whereas Freud tried to analyze those rules and later define their structure, Kafka showed that the rules are always hidden. You cannot touch them. You cannot see them. You cannot define them. But they are still there. Fanny, Zizek, and Piotr grew up with rules. Those rules are not only political or religious; they are intertwined with their innermost feelings. Breaking that kind of rule will always make you feel as if something internal is broken, too. It will always mean transcending yourself, reinventing yourself, seeing in your enemy the opposite of what you learned to believe. This is why most people are so afraid of changes. It’s why tikkun is so difficult.

BP: When Fanny finally finds Zvi Meir, he is a pitiful character rather than a malicious one. How does this change the way we view her quest?

YI: When I first published this book, a lot of readers told me they disliked Zvi Meir. He is the one who caused all the trouble, and for what? For the world to recognize his self-assumed genius? I was actually surprised by that, because for me, Zvi Meir is not evil. On the contrary. Zvi Meir, just like Fanny and Zizek, wanted to redefine his own existence. In fact, Fanny also leaves her husband and five children without ever knowing if she is going to return. So, after all, Zvi Meir and Fanny are not that different in terms of their motives, and Fanny realizes that when they finally meet. I think that the meeting between them, which is supposed to be the peak of the story, is also a crucial anticlimax.

BP: Despite its many dark recesses, there’s a wonderful underlying optimism to The Slaughterman’s Daughter. How important is the belief that goodness will ultimately prevail?

YI: Actually, I rewrote the end of the book after initially writing a pessimistic ending. Fanny resisted that ending and I didn’t want to get into trouble with her. She was right. She didn’t want to end like Anna Karenina or Madame Bovary, even though that might very well have been the case for a woman like Fanny at that time. But since I’m not constrained by the boundaries of reality or history, I wanted her to succeed in her crazy journey, and this is where the term “historical novel” is misleading. Not because my aim was just to present an unrealistic fable or to inspire our imagination. My aim was to show how reality could be — how history could take a different course, and not only in the form of a magical romance. I think that these are the roots of my infinite optimism, which is essentially related to the possibility of writing, of playing with what is real, of rethinking the factual.

For ten years, Bram Presser schlepped around the world as the singer of iconic Jewish punk band Yidcore before turning to writing. His debut novel, The Book of Dirt, was released in Australia to great acclaim and won numerous major literary prizes. It was recently published in the USA where it won the National Jewish Book Award for Debut Fiction.