Janny Brilleslijper, image courtesy of the author

“When you have to fight, you have to fight. You cannot become untrue to yourself. You cannot fool yourself either. This is what we believed in. We did what we had to do, what we could do. No more and no less.” ‑Janny Brilleslijper

“It’s a really old house, you do realize?” The realtor looked at us with raised eyebrows, a frugal smile on his lips. We stood in the orchard and looked around, in awe. We were locked in by nature in full bloom. On one side the dense forest, with a narrow path leading straight to the sea. On the other side wild heathlands, covered with a purple glow as far as the eye could see. We nodded and smiled at the estate agent walking unsteadily through the grass, his suede shoe squashing an overripe pear; our eyes were fixed on the house behind him, which rose out of the landscape on a hill. It was made of robust stone, with a thatched roof and oxblood red shutters flanking its windows.

It was the summer of 2012 and — together with our three small children, a German Shepherd, three cats, and two guinea pigs — we moved into The High Nest in Naarden, a small village just twenty kilometers away from Amsterdam.

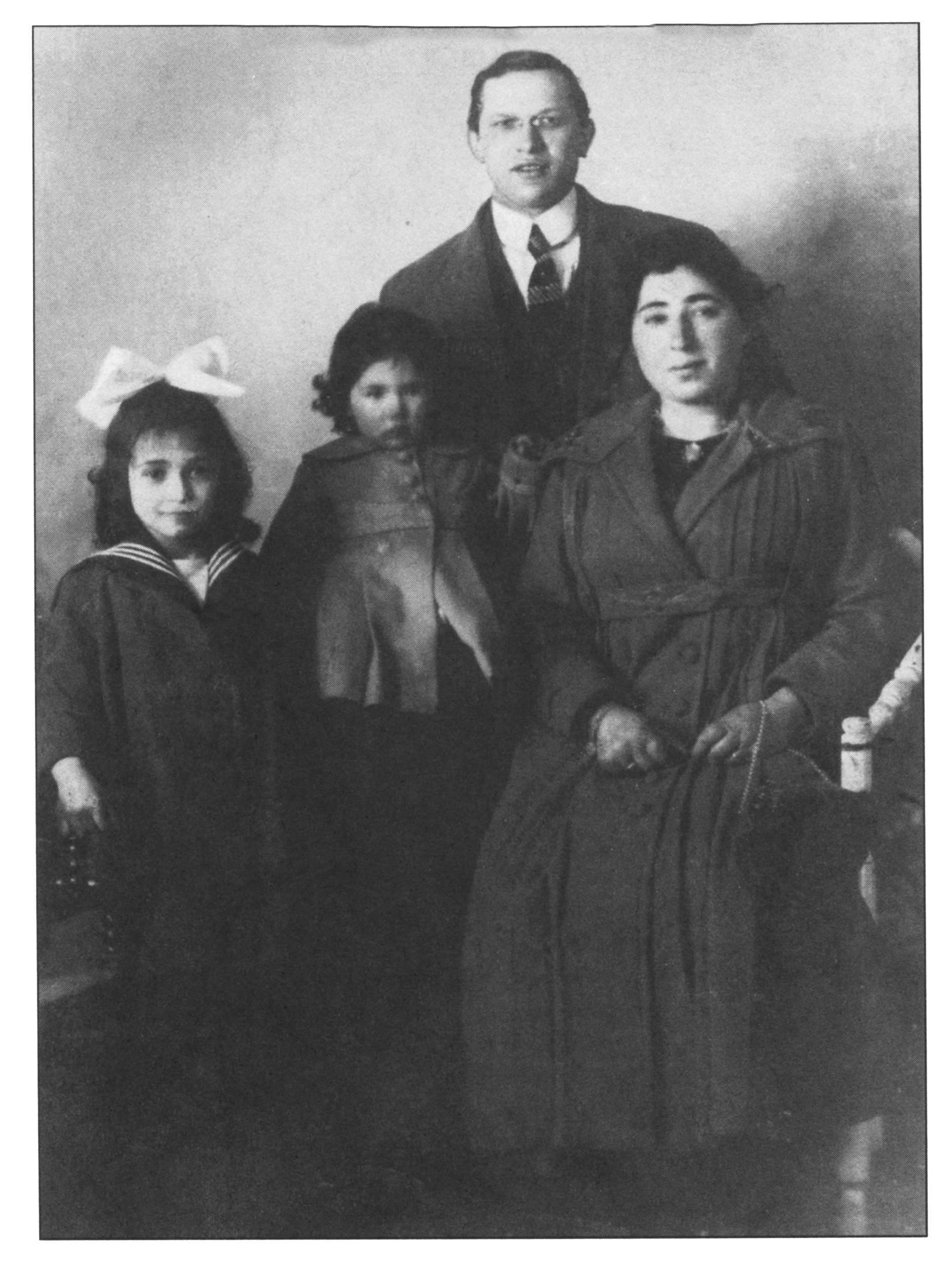

The family Brilleslijper, 1920

We restored walls, sanded stairs, peeled off the carpet, and removed panels that exposed ceilings with ingenious beams; in almost every room we discovered shutters in the wooden floors and hiding places behind old paneling. In these secret corners we found candle stubs, sheet music, old resistance newspapers. And so began the reconstruction of the history of The High Nest.

In the underground, The High Nest was soon known as the safe haven in the forest where many Jewish artists and resistance fighters and their families hid.

An astonishing history, it turned out, covering a part of a wartime past that was unknown to the public. The High Nest was an important hiding place and resistance center at the height of the Second World War, when trains were headed for concentration camps at full capacity and the Endlösung der Judenfrage (Final Solution to the Jewish Question) was successfully taking shape all throughout Europe. It was run by two fearless Jewish sisters, both young mothers in their twenties: Janny and Lien Brilleslijper. From all over the country, Janny and Lien took in desperate Jews; the house was inhabited by a core group of seventeen adults and children, which grew to more than twenty and sometimes thirty people.

In the underground, The High Nest was soon known as the safe haven in the forest where many Jewish artists and resistance fighters and their families hid. Resistance papers were being printed, opera nights and Yiddish classes were being organized, and Jewish culture flourished, at a time when 75% of the Dutch Jewish population was systematically being murdered — the highest number of Western Europe. All under the nose of Nazi sympathizers and national socialists, like National Socialist Movement (NSB) founder Anton Mussert, who lived around the corner with his mistress.

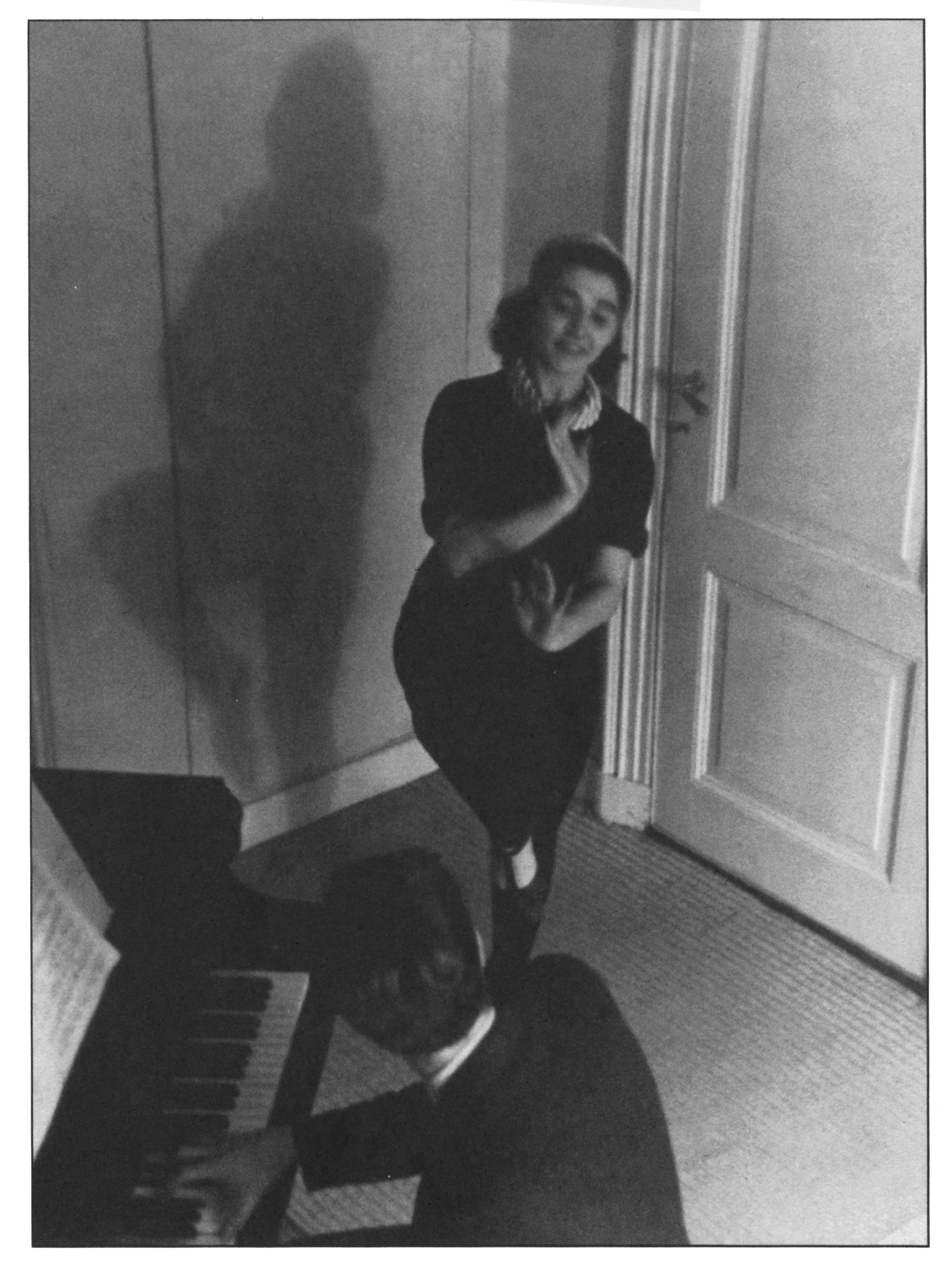

Lien and Eberhard, 1939

On July 10 1944 the worst happened: The High Nest was betrayed and its residents were captured by infamous Jew hunters. The entire Brilleslijper family was deported to camp Westerbork, where they met the Frank family, who had just been uncovered in their secret annex in Amsterdam. Sisters Anne and Margot Frank were ten years younger than Janny and Lien. While the Allies were advancing and the liberation was approaching, the Frank and Brilleslijper families were deported together, on the very last train to Auschwitz on September 3, 1944. From then on there was only one goal: stay together and survive. Janny and Lien signed up as nurses and managed to withstand the dreaded selections of doctor Mengele. When they were deported to Bergen-Belsen in November 1944, they thought it meant their escape from the gas chambers. But Bergen-Belsen had sunk into a pitch-black chaos of disease and starvation, dead bodies piled up all over the camp grounds. Janny and Lien left their family behind in Auschwitz — just like the Frank sisters — and they cared for the teenage girls until Margot and Anne succumbed to typhus. Just a few weeks later, on April 15 1945, British forces liberated Bergen-Belsen. To their astonishment, they found 13,000 corpses and 60,000 emaciated prisoners on the camp site — two of whom were Janny and Lien. They made it.

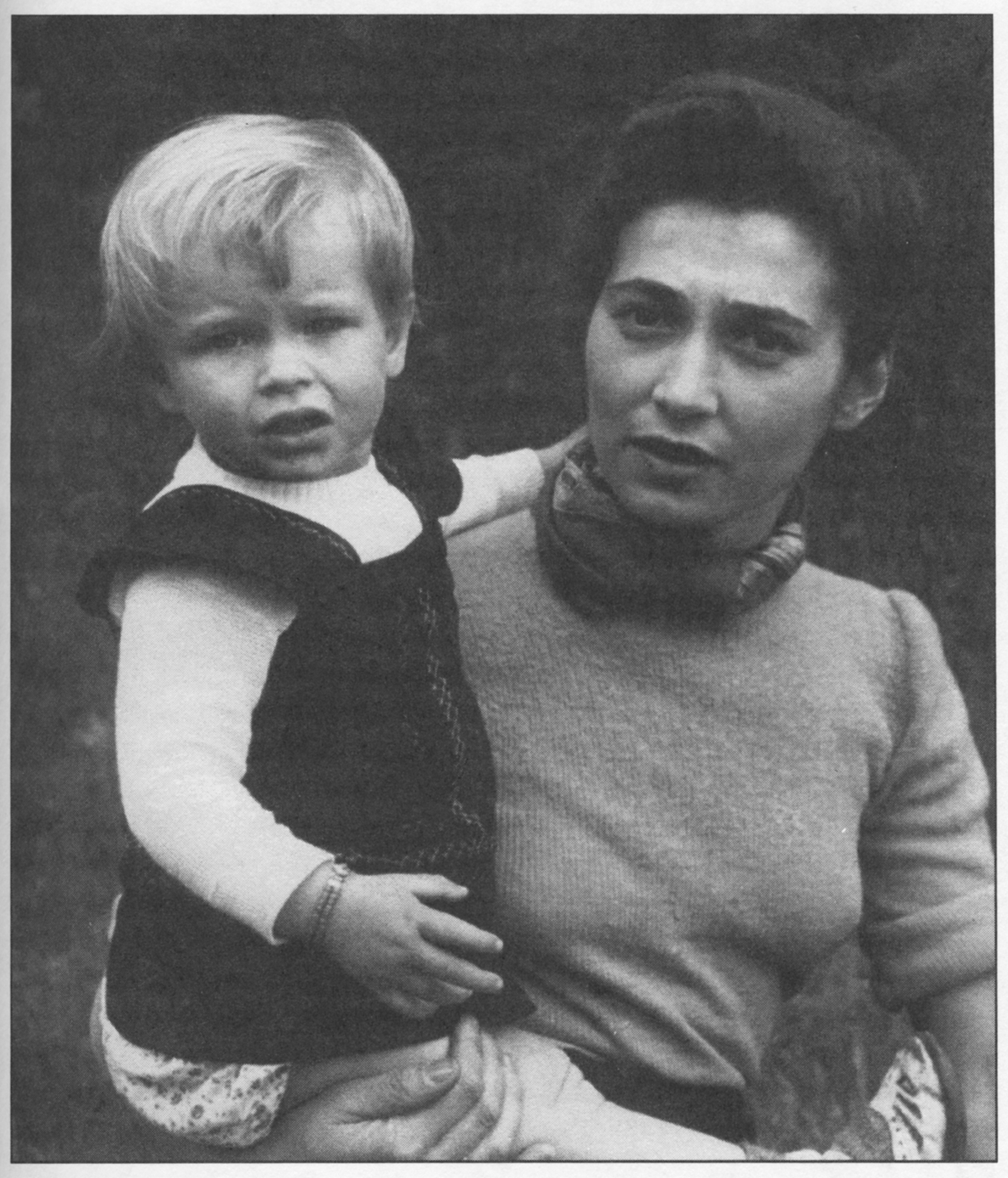

Lien and Kathinka, June 1943

After six years of research I managed to piece together this incredible story of two Jewish sisters in the resistance, The Sisters of Auschwitz: The True Story of Two Jewish Sisters’ Resistance in the Heart of Nazi Territory. It is a story about how ordinary people behave in exceptional situations — some with courage, others with silence or cruel oppurtunism — and includes the events that occurred at The High Nest during Nazi occupation, from house concerts to theft to murder.

The children that went into hiding at The High Nest are now in their seventies and eighties. They came to visit us from all over the world and witnessed our children playing in freedom where they had played during the war. The desk where my book originated is right above the hatch in which all identity papers were hidden when the Jew hunters surrounded the house. It’s a daily reminder that the true renovation of The High Nest was not in the restoration of the walls, but in the reconstruction of the exceptional events that took place here.

The Sisters of Auschwitz by Roxane van Iperen

Roxane van Iperen (1976), is a former lawyer, investigative journalist and author. Her debut novel was awarded a literary prize. Her second book is based on the story of two Jewish sisters heading a safehouse during WWII: The High Nest. In 2012, Roxane moved into The High Nest, and embarked on a six-year investigation, leading to The Sisters of Auschwitz.