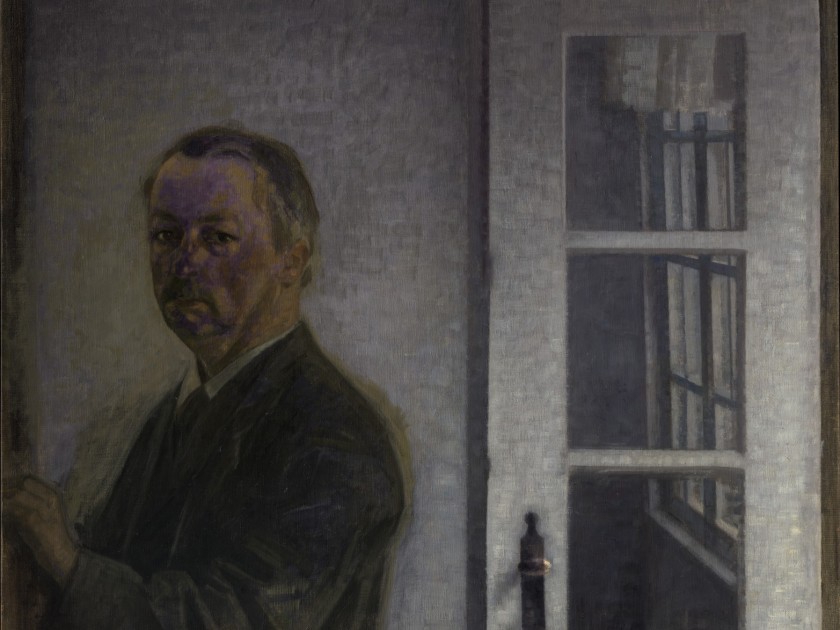

Self-Portrait at Spurveskjul by Vilhelm Hammershøi (1911)

Gift of Charles Hack and the Hearn Family Trust, in honor of Keith Christiansen, and in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2020, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Congratulations to the 2021 winner of the Paper Brigade Award for New Israeli Fiction in Honor of Jane Weitzman: Oren Gazit, for The First Ending, Then the Second translated by Jessica Rutman Setbon. This selection from the winning title can be found in the 2022 issue of Paper Brigade.

The Paper Brigade Award for New Israeli Fiction in Honor of Jane Weitzman seeks to honor an outstanding short work or excerpt of Israeli fiction published in Hebrew. The goals of this prize are to introduce American readers to new Israeli writers; to help Israeli writers gain access to the American market; and to interest American publishers in publishing new Israeli fiction.

In his debut novel, Oren Gazit delivers an incisive commentary on the potential distortions of democracy. The story begins in 2028, in a theocratic Israel that limits freedom of expression — political, cultural, and social. Flags wave atop every building, and families who don’t conform to the state’s ideal are penalized. The narrator, Avraham, a well-known playwright and songwriter, has sold his soul to remain on the Ministry of Culture and Patriotism’s list of approved artists.

As Avraham records his memoirs for his daughter, Dana, he recalls a fateful night a decade ago, when an explosion shook the walls of their Tel Aviv home. With him were Dana, then a resentful teenager, wheelchair-bound after a car accident-cum-suicide attempt; Maggie, Avraham’s eccentric British mother-in-law, whose theatrical posturing hides her inner turmoil; and Dalia, an aging actress and Avraham’s former lover. The foursome is haunted by the memory of Avraham’s late wife, Adina, who was killed in a car accident.

Throughout the night, surrounded by a pervasive sense of danger from outside, the characters act out their own internecine drama, each attempting to snatch away the masks that obscure the true nature of the others.

—Jessica Rutman Setbon

Adina’s photo fell off the shelf and shattered. A shock wave rattled the windows and the door. A chorus of neighborhood dogs began to bark. I remember you shouting, “Dad, what was that?” and the intense boom that followed. Our ears rang.

Maggie was the first to speak. “It must have been a terrorist attack. It sounds like it was really close, maybe near Ichilov Hospital or the shopping center.”

“Maybe it’s at Arlozorov train station,” Dalia said. “I’ve always said there would be a terrorist attack there one day, God forbid.”

I remember silence and fear, and loud, racing heartbeats. I remember our eyes darting to each other’s faces, to the crooked pictures and a shattered vase. No one screamed or moved. That’s what was strange, I think — we all froze in place, accepting the silence and the echo that ping-ponged off the walls.

A tumult of sirens made their way from Ichilov to the site of the blast. A few minutes later, the television screen was filled with passersby. They gripped the microphone and insisted, “I never thought this could happen in our neighborhood.”

I helped you get out of bed and roll into the living room. Together we watched the images of the shopping center and the corner store where the terrorist had blown himself up — the same store we visited every day to buy rolls and sliced cheese. We murmured how terrible it was and how close it had been. Maggie said that Dalia had mumbled “God forbid” several times. She’d counted how many times.

_______

“It’s a good thing that Adina ran away to me in England. She had to get away from this crazy country you live in, full of terrorists who murder people in the streets.” The ancient phone was plagued by interference and its battery was dying, but Maggie’s screeching came clearly over the line.

You were six years old at the time. We were sitting in that same living room. I handed you the phone, and Adina got on the line. I couldn’t hear her voice as she answered you — I heard only your side of the conversation.

“Hello,” you whispered.

“Mommy, why didn’t you take me with you?”

“Is it because I don’t like being there at Maggie’s house?”

“If you want to, so come home. But if you don’t feel like it, that’s okay, too, Mom. Whatever you decide.”

“Yes, I’m cleaning up my room, and I’m doing my homework with Dad, and I’m going to ballet.”

“Mommy, why didn’t you take me with you?”

At night I heard your sobs. I couldn’t stop them — not with a sugar-laced bribe, not by shouting. It wasn’t your fault, understand? You were a little girl when she ran away to London and left you with me. You felt unworthy — she’d saved herself, but left you behind. Adina ran away because she was petrified. She’d broken our agreement. She introduced him to you, and took you to the shopping center and the safari park with him. But instead of reassuring you that you didn’t have to worry about me discovering her secret, I kept asking you if you were worried about suicide bombers. I wouldn’t have been angry with you, if you’d told me. If only I’d known that that’s what you were hiding. You see, there were no secrets between me and Adina. We shed our secrets once we began to speak the truth. We carved it into each other’s backs.

“I liked it when we were together, the three of us. I could live like that, Avraham,” Adina had said. “With him and Dana.” You see, everything between us was out in the open. Toward the end, our love was the only thing that remained hidden.

Years later, you told me that I abandoned you that night. I didn’t promise you that everything would be all right. You couldn’t trust me — not when you were six years old, and not as a sixteen-year-old in a wheelchair.

“Don’t promise her anything,” one of your boyfriends told me. “If you promise her something, she just focuses on proving that it can’t happen.” I told him that I’d made you too many promises that I hadn’t kept. So it was my fault that you couldn’t believe anyone’s promises.

“You?” the boyfriend asked in surprise. “She never mentions you when she talks about that. Only her mom. She was the one who didn’t keep her promises. One day she promised she’d come home, but then she died.”

______

The television broadcasted a live, impromptu press conference with the police chief. He said that there had been no advance intelligence about the terrorist attack, although the minister of defense had announced previously that there had been advance information, but no specific warning. The police chief repeated that this was a suicide bomber, although the emergency services spokesperson who’d been interviewed before him explained that at the moment, there was no confirmation that the terrorist’s body had been found.

I remember silence and fear, and loud, racing heartbeats. I remember our eyes darting to each other’s faces, to the crooked pictures and a shattered vase.

The police chief asked the public to “Let the security forces do their job. It’s very hard to predict the actions of a single terrorist.”

Dalia shouted at the television, “If they’re so hard to predict, what are you all so busy at?”

Dalia rubbed her cell phone on the edge of the sofa. She tapped it again and tried to dial. She said all the lines were down and she couldn’t get through to her daughter, Efrat, to tell her she was all right. Then she stood up.

“Tell me if you’re planning to write for me. If not, then I’ll go home. This is no day for celebrations.”

“Why are you insisting? There are plenty of others who can write lyrics for you.”

“You know why, Avraham. They aren’t interested. Those people don’t even call me back. It’s been years since they’ve returned my calls.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Really. Another one who’s sorry. I’m still waiting for those lyrics that you kept promising me, right here in this living room. Until the day I heard Chava Alberstein singing a new song on the radio. When it ended, I finally realized why it sounded familiar.”

Dalia collected her beaded handbag. In it, all the colors of the rainbow shimmered uncomfortably.

“Feel better, sweetie,” she said to you. I didn’t feel I needed to say anything to her. Years later, I explained to you that sometimes Dalia didn’t need explanations — she just needed an audience.

“You probably know that Adina called me.It was after I left you that message that you were a son of a bitch — excuse my language — for giving away those lyrics you promised me,” Dalia said to me as she reached the front door. “She said she’d heard that I was upset. At least after she died, you grew some balls. Now you can tell people things to their face, instead of them hearing about it on the radio.”

____

After each of my quarrels with other people, Adina would call and apologize for me. She’d sit in the wooden chair in the dining nook, a Parliament burning in one hand, in the other the letter of apology that I’d carefully composed and read to her the night before. As Adina read the letter, we’d snicker and picture the insulted person’s face swelling with pride as they listened to the empty words. I’d tickle Adina’s stomach with the soles of my feet. Then she’d slam down the receiver, and we’d burst out laughing.

After she made my apology to Dalia, Adina chuckled. “She said that you’re a shit. And she also said that she can hear you in the background, giggling like a little girl.”

When we laughed like that, I would always give Adina a hug, a symbol that we were a team. Then we would argue. You probably still remember the sounds of our arguments — your childhood refrain. We argued about everything. When the radio kept playing the song “Everyone’s Got It,” Adina shouted at me, “Why can’t you write something like that?” When Prime Minister Ariel Sharon wanted to evacuate seventeen settlements, she demanded, “I don’t understand how you can think he’s right.” When I found her pink slip in the laundry pile, and I didn’t recall her wearing it on any of the nights she’d slept beside me, it was “Find something else to worry about.”

____

The television screen was red and filled with blaring headlines. One of the reporters was standing beside the train station that bordered our backyard. He said that a neighbor had found the body of an elderly woman. Apparently, the terrorist had hidden there throughout the day until he went out to perform the attack. The television station’s military reporter added that there may have been two or even three terrorists, and that they might still be in the neighborhood.

“It’s a very unusual situation,” said the announcer beside him. “I’ve just received a report that all inhabitants of the area are requested to remain in their homes until the search for the terrorist or terrorists has been completed.”

The wailing of the sirens outside was interrupted by an announcement: “Stay in your homes. Lock the doors. Close the windows!” The military reporter in the studio said that the most important thing was to remain calm and drink water.

“Drink water? That’s what they told us in the Gulf War!” Dalia said. “I’ll try to get out quickly. I can probably grab a cab up on Ibn Gvirol.”

Maggie went around closing the blinds. She asked me to go upstairs and check that the windows in the attic were locked. I wasn’t afraid, just worried and uncomfortable. The overwhelming fear came later — see? Many long days after that night was over.

From the window of my bedroom on the second floor, I watched Dalia on the path from the house. Her disjointed way of walking has always amused me. She stretched her head forward like a cartoon character, her body following as if in pursuit.

“First get organized, then start walking!” I used to shout at her during rehearsals.

“Get organized,” I whispered that evening beside the window. I saw the ambulance turn left into the street. Dalia stepped from the sidewalk to the road and fumbled in her handbag. Then I saw the handbag fly up between the branches of the rubber plant and land on the lemon tree at the entrance to the house. Its contents rained down in a deluge. Through them, I saw the ambulance drive up onto the opposite sidewalk and stop.

I ran downstairs and shouted, “Dalia got run over!”

“When did she manage that?” Maggie asked.

The women close to me have an inexplicable attraction to car wheels. I’ve often been asked to explain this in casual conversations with friends or in interviews. I also ask myself about it whenever I happen to hear those stupid songs about fate, when I don’t cover my ears quickly enough. There is no such thing as fate — the theater of life has no director. Recently you told me you thought that accidents might run in our family. Like other families that hand down traumatic experiences in their genes, you said, our family had a strong epigenetic experience of tragedy.

“So how do you explain Dalia’s accidents?” I ask you. “She’s not related, so an explanation based on our family’s genes doesn’t apply to her.”

You laugh — I love to hear that sound.

“I can think of two explanations,” you say. “Either she’s become family over the years, just like there are couples whose bacteria become similar. Or else she’s so desperate that she’s willing to get run over just to prove she’s close to you.”

I repeat that it’s only a coincidence. I say that if there’s one thing I inherited from Maggie that I’d love to get rid of, it’s the family folklore. In my weakness, I recognize its ridiculousness, and I laugh at it still. You do, too. We both recall those precious pearls of Maggie’s wisdom. Whenever she saw a beautiful young man, she’d whisper, “I hope he doesn’t come to a bad end, like James Dean.” For a proud soldier, it was, “I hope he doesn’t end up like General Patton.” And for a couple behaving affectionately — “I hope they don’t end up like Princess Di and Dodi.”

We both love to laugh at her irrational fear of cars. Her whole life, she refused to learn how to drive. “People don’t need to drive machines,” she used to say. “Either the machine should drive by itself, or people should carry each other on their backs. You both have your licenses,” she would mock, “and look how I’m still carrying all of you on my back.”

I ran to the gate. Dalia lay on the sidewalk, blood dripping from her forehead.

“He ran into me. His left mirror hit me on the head. That nutcase! He was driving way too close to the sidewalk.”

The paramedic from the ambulance began to bandage Dalia’s forehead and instructed her to remain lying down. “Lady, you might have bruised your spine. It’s dangerous, I’ll have to tie you to the stretcher.”

“Help me get up, young man,” she told him, attempting to stand. “None of that nonsense about tying me up. We’ll do that later.”

Then she leaned over and vomited. The paramedic put his arm under her back for support and handed her a bottle of water.

“Someone call Efrat and tell her that I was hit by an ambulance,” she said.

The paramedic tried to convince her to go to the hospital. He warned me about concussions and back injuries, internal bleeding, coagulation.

“Better to die in Avraham’s house on the sofa than in the emergency room at Ichilov,” Dalia said. “At least people will say, ‘She was working right up until the last minute!’”

Then she ordered me, “Stop looking at me like a statue. Put your hand under my back and help me get up, please.”

“Don’t get up, lady!” the paramedic shouted.

“I’ve got to wait for the police,” said the driver.

Dalia lashed out at him. “You cut my head off and then you scream at me! You fool! Watch out, those crab lice will make you itch.”

“Hey, I know that line!” the ambulance driver said. “That’s what the Polish woman said to her husband at the beginning of the sequel to Lemon Popsicle.”

“This lady here played the Polish woman in that film,” I explained.

“No, no,” the driver said. “It was that other actress — I don’t remember her name, but she was great. She died a while ago. Now, you take your mother to the hospital because she’s confused, and that’s not a good sign.”

“Who do you mean, his mother?” Dalia asked. “Are you talking about me?”

“You see, mister,” the driver said, “she doesn’t even remember who she is.”

“I’ll sue you!” Dalia said to the driver. “For the accident, for what you did to my head, for all the stuff in my handbag! Who knows where it is now. I’ll take every last penny of yours! You’ll be sleeping inside that ambulance.”

Slowly Dalia stood up and leaned against me, her arm around one of my shoulders, her head resting on the other. We walked down the path toward the house. At each step, she groaned and gasped. A bead of sweat dripped from her face onto my arm, and she wiped it away quickly with her sleeve.

“My head is exploding. I’ve got to lie down. But don’t take advantage of me, not on our first date,” she joked.

“Stop, you’ll exhaust yourself,” I demanded.

“It’s my age, Avraham. If you’d have come to my sixtieth birthday party, you’d know how old I am,” she said. “When I hear strange sounds in the night, I know they’re coming from my bones.”

Back in the house, the television hummed. Dalia lay down on the sofa. Tears trickled down her neck — at least, I remember something like that.

“Why me?” she mumbled. “Why does this always happen to me?”

Years ago, at the Eurovision preliminaries, she’d made that same complaint when she’d sung “Tomorrow’s Parents.” The song had been submitted in the category for songs without performers, and the Broadcasting Authority committee had offered it to her. Throughout the rehearsals, she’d whined to anyone who crossed her path. Why me? she’d demanded. Why had the committee given the dumbest song to her? Why had she ever agreed to perform it?

Then she’d argued with the director. He’d wanted to begin filming the song with her in profile, but Dalia objected. “You’re doing that on purpose, so right at the beginning everyone will see how the kids ruined my boobs.”

After that, she made the rounds of the participants and the stagehands, repeating a joke about the dress she was wearing: “It’s the perfect combination of bride and whore — for universal appeal.” Before the live broadcast, she burst into tears. She came to me and said, “Maybe I can still quit, so I won’t embarrass myself. What do you think, Avraham? Or maybe you’re glad I’m participating, because then it will be easier for one of your songs to win.”

When she won second place, no one went over to congratulate her. From the winners’ table, I watched her break down again. Maybe the tears left damp trails on her cheeks, I don’t remember — just like I can’t recall if she cried when she lay on the couch that evening and mumbled, “Why didn’t they choose me? Why does this always happen to me?”

____

I never liked that shallow tune that Dalia had sung. A few years ago, I was jealous of her when I read that she’d received an unprecedented sum for the rights to it. It had been chosen for the new Ministry of the Interior ad campaign on the definition of a “real” family. According to the new regulations, a family with a father and a mother was a “red” family, and it would receive the full state benefits. Families with one parent or two parents of the same gender were “yellow,” and they had to pay a special tax to the state. They weren’t recognized as a family unit by the Ministries of Education, Treasury, or Welfare.

For most of my life, I was afraid of being replaced. By the cancer that devoured my parents when I was a teenager, by Adina’s choices.

“It’s terrible,” you said, when I called and told you the news. “Do you realize that means we’re a defective family?” For a moment I felt like saying I didn’t care — that you were over eighteen, so the law didn’t affect me. But I didn’t say anything. At the end of the conversation, I mentioned Dalia’s song.

“Why did they choose that awful song?” I protested. “I have so many songs about parenthood. It makes no sense for state money to go to a songwriter who doesn’t even live in Israel, and to a composer who everyone knows votes for an Arab party.”

____

“How long will we be stuck here?” Dalia asked. Maggie told her that she thought it would be over soon. She brought out sandwiches from the kitchen and placed them on the coffee table in the living room.

“That shot they gave me killed my appetite,” Dalia announced. “I’ve got to check what it was so I can ask for some more. What did you make?”

“Something I like. I can live on bread and cheese.”

“Just on that?”

“Yes.”

“So what are you, a rat?”

Then Dalia smiled at me and said, “That’s a line from a musical that I’ll never forget — even when someone hits my head with a car mirror.”

___

I don’t recall cringing then, as I am now while I write this. The theater people had objected when Dalia was cast as the lead in Annie Get Your Gun. The artistic director had wanted a different actress, who was receiving a regular salary from the theater and who didn’t have another role at the time. I didn’t object to the theater’s decision. The second actress was just as good, and I also didn’t want to be marked as someone who wasn’t helping the theater solve its crises. More and more songwriters were attempting to write dramas. I preferred not to rock the boat. I wanted the theater to remember that I was a soldier who could be sent into any battle.

For most of my life, I was afraid of being replaced. By the cancer that devoured my parents when I was a teenager, by Adina’s choices. You also tried to replace me with your exploitive, inaccessible boyfriends. That’s exactly how you described me during those years. That I was afraid of being replaced by your boyfriends. That they would detect the big lie, the man with nothing inside of him, and then I would disappear.

There’s one song I always turn off whenever it comes on the radio: “Be My Friend, Be My Pal.” That childish wish is completely illogical. Friends come and go — even old ones. They disappear in times of happiness, and they suck your blood in times of pain. Friendship is nourished by a false sense of cooperation. You feel good when a friend does the right thing. The rest of the time, friendship is like soap bubbles that blow away in the wind. It’s in their nature to pop. It’s hard to understand the human need for those bubbles to stay whole. Often, a beautiful friendship forms between fellow actors in a play, but when the play ends, it disappears. In those moments, theater really is larger than life. I’ve learned that even a brother is temporary. He leaves nothing behind.

In my professional world, I never allowed myself to be replaced. I never permitted life’s obstacles to block my path. I never forgave a singer who sent me a score and then chose lyrics composed by a different writer who was given the score later on. I didn’t agree to give my play to a producer who was depending on it to avoid bankruptcy, when two years earlier he’d decided to work on a comedy with another translator. Once, a certain successful Mediterranean singer recounted in an interview that he’d cut my song from his latest album at the last moment and replaced it with one he’d written himself.

I didn’t let this slide. A week later, the tax authorities appeared at his home and walked off with his safe and the four million shekels he’d hidden in the walls of his penthouse bedroom.

___

“They’re idiots for replacing me at the theater. I could have been a wonderful Annie Oakley,” Dalia said. “But that stupid director insisted that I sleep with him, and I just wasn’t up to it. The very thought made the stitches from Efrat’s birth hurt. I told him to go to hell, that I wasn’t going on vacation with him to any hotel in Tiberias. So he took that whore with him instead — excuse my language, there’s a child here.”

Every so often, I make sure there’s no change in the Wikipedia entry for Annie Cole — the name of the person who wrote Dalia’s big hit of that period, “Don’t Give Up on Me.” It amuses me that this single song is the answer to a popular trivia question, “How many songs did the songwriter Annie Cole publish?” I’m certain Dalia never suspected that I was the one who’d left the lyrics in her mailbox on Jordan Street.

“I don’t get it,” Adina had complained. “Do you have to make it up to her because they didn’t want her? You don’t owe her anything. If you feel like you owe her something, go give it to her in person, like a real human being. I can’t stand how you’re always hiding from real life. Sometimes I feel like I married my mother.”

Oren Gazit was born in Ramat Gan in 1971. He is the head of the documentary and docu-reality department at Israel’s Channel 13. Gazit is a single parent to twins, a boy and a girl.

Jessica Rutman Setbon is a native San Antonian who studied Japanese at Harvard, made aliyah in 1992, and has been a Hebrew – English translator for over thirty years.