When I started out in TV news in Binghamton, New York in 2000, every assignment seemed to be out of my comfort zone. My parents raised me and my five siblings in Tenafly, New Jersey with a heavy emphasis on manners and respecting other people. They always encouraged me to speak my mind, but they probably would have frowned upon me knocking vigorously on someone’s front door just after their relative has endured a catastrophic accident. As an inexperienced reporter, I used to hope that people wouldn’t answer the door. I wished I was invisible when they did, as I apologetically explained that I was there to ask questions about an injury, death, or scandal. I was embarrassed to be there, ashamed to be imposing on their tragedies. I generally avoid conflict in my personal life, and I dreaded being scolded or yelled at, even though, deep down, I thought I deserved it.

Getting out of my comfort zone to write More After the Break meant considering whether my presence had exacerbated or mitigated a family’s pain — whether our news stories had helped shine a light on important issues or directed unwanted attention on a person who was already hurting. Reporting an accurate story is always a paramount concern. But equally interesting to me is how the people I have met in this business continue to influence my choices long after I leave their living rooms or the breaking-news scene. As much as the stories we write for the news are intended to leave a lasting impression on our viewers, they make an indelible mark on us journalists as well.

Many of the people I have covered on the news turn to religion and faith for comfort following a major life crisis. I, too, have searched for spiritual guidance and a higher purpose after bearing witness to the agony of so many. I converted to Judaism at age thirty and am still learning how to apply its lessons to my everyday life. I was raised Protestant, and I spent most Sunday mornings in church with my family. I met my future husband, Scott Ostfeld, in Italian Renaissance Sculpture class at Columbia. We were married by a rabbi and a minister in 2003 and agreed to raise our children Jewish. When I was pregnant with my son Trevor in 2006, I did what any good reporter would do: I researched and interviewed, enrolling in a conversion class in Morristown, New Jersey, even though I had no intention of converting. I simply wanted to learn, so I could be a well-informed mom of a Jewish child.

I converted to Judaism at age thirty and am still learning how to apply its lessons to my everyday life.

In my first year of motherhood, I realized that while I never objected to practicing a different religion than my husband, I felt disconnected, a partial participant in my son’s religious life. Whether it was at his bris, or in Mommy and Me class at the United Synagogue of Hoboken, I felt like I was standing on the sidelines. Having been raised with a strong sense of faith by my parents, I wanted to give my children that same gift. In early 2008, a month before my daughter Vivian was born, I converted to Judaism.

Taking the conversion class offered me the opportunity to reflect more deeply on Jewish Holy Days I had glossed over in the past, when I sat half-listening in temple with my in-laws, waiting for the English language portion to start. I was particularly intrigued by the tradition leading up to Yom Kippur, when it is customary to contact people you feel you have wronged and apologize. From my rabbi, David-Seth Kirshner at Temple Emanu-El in Closter, New Jersey, I learned that this humility is intended to help us acknowledge our mistakes and move forward into the new year with healthy relationships.

I wonder if part of the reason I wanted to seek out people from my news past for More After the Break was to determine whether I owed them apologies as well. Did they resent that I monopolized the time after a trauma when they should have been comforted by family and friends? Did they wish that their family’s struggle had been kept private? Did they feel they didn’t have a choice when I came knocking?

Dozens have slammed the door in my face before I’ve even finished my interview request, a straightforward refusal I have grown to accept. But the prospect of someone agreeing to an interview, and then that acquiescence metastasizing to regret once their story has gone public, is far more upsetting.

My conversations with the people I have featured in these pages have been complicated, but ultimately reassuring. The passage of time since my initial reports aired has highlighted how constructive change can and does happen when unjust and tragic events are publicized. As a local news reporter, I cover the best and the worst of what happens in my home state of New Jersey. I would like to believe that by broadcasting grief and pain and injustice, we inspire introspection in our viewers. Our news stories are proof that no matter how hard we try to protect our loved ones, they can be cruelly injured or even killed. Knowing that we don’t have total control is frightening and unnerving. The antidote is to enjoy every day, and to be kind to each other. The moral ambiguity of what I do for a living only emerges as a positive if the stories I write have the same ripple effect on you as they have had on me.

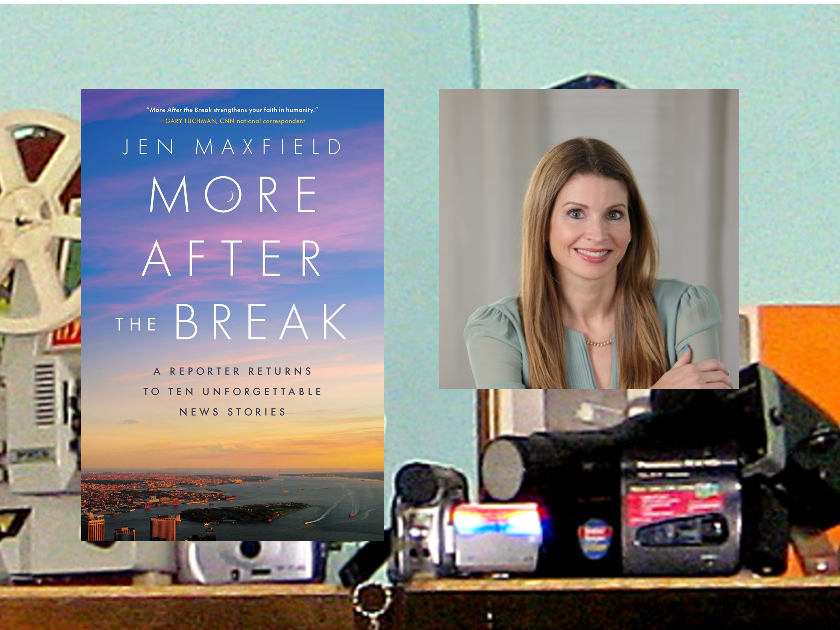

Jen Maxfield is an Emmy-award winning TV news reporter and anchor who has covered New York City for two decades. Maxfield is also an Adjunct Professor at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. Maxfield has had the opportunity to meet tens of thousands of people covering news events over a wide range of topics, including politics, schools, criminal justice, health, business, weather, and human interest stories.