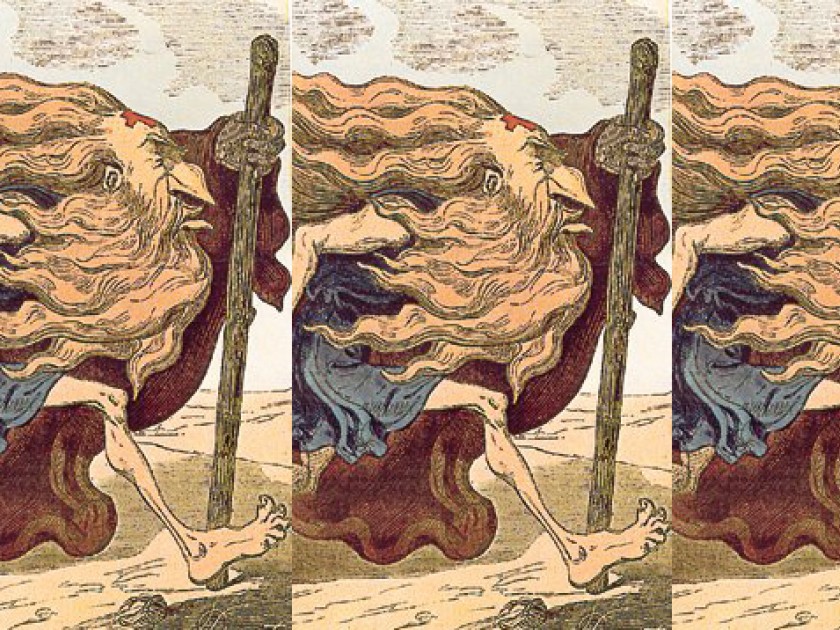

Header photo credited to Paul Gustave Doré.

My grandparents on both sides of my family escaped from Nazi Europe in 1939, almost too late. My father and his parents left Czechoslovakia for Palestine thanks to exit permits and entry visas obtained from one of my grandfather’s cousins, a doctor whom the authorities had barred from emigrating. My mother’s father, also a doctor who had arrived in the United States in the mid-1930s, brought his parents and siblings over from Lithuania thanks to a grateful patient who signed fourteen immigration affidavits.

I come from a family of refugees, but I never thought of it that way when I was growing up. “Refugee” wasn’t a word we used. My relatives seemed like ordinary immigrants to me. My father’s parents, whom we often visited in Israel in the summers, spoke German with my uncle, Hebrew with my cousins, English with my brother and me. My grandmother cooked wurst and wiener schnitzel and baked fabulous Viennese cakes. She told happy stories of skiing in the High Tatras and picking mushrooms in the forests near Brno. The places she talked about seemed as distant, and as benign, as the images in the few faded pre-war family photographs we possessed. By then, Czechoslovakia was sequestered behind the Iron Curtain and Lithuania impossible to find on any map. The world they’d left behind had disappeared.

For a long time, I assumed the anti-Semitism that had driven my family out of Europe had been left behind as well. But by the early 2000s, reading about the threatening anti-Semitic rhetoric of Iran’s Ahmadinejad, the virulent anti-Zionism of the European left, and the far-right conspiracy theories claiming that the 9/11 attacks had been carried out by Israelis and Jews, I felt unmoored.

In 2005, I came across a New York Times Magazine piece about an exhibition of anti-Semitic cartoons to be displayed in a London museum. The show juxtaposed medieval drawings of Jews as child-eating spiders, Nazi caricatures of the monstrous, hook-nosed “Eternal Jew,” and modern anti-Israeli images based on the same anti-Semitic tropes. A 2003 cartoon from the British newspaper, The Independent, for example, depicted Ariel Sharon with a bloody Palestinian child dangling from his jaws. (The caption read, “What’s wrong…you never seen a politician kissing babies before?”) The collection was controversial. Did exhibiting anti-Semitic images neutralize them — or give them renewed strength? Was it better to remember or forget?

I started working on a novel whose main character was a Jewish collector of anti-Semitic cartoons, modeled after the owner of the collection displayed in the London show, a British physician and Orthodox Jew. I imagined my character as a man obsessed with figuring out what could motivate and sustain that kind of hate. In 2004, the U.K. had experienced a record 532 anti-Semitic incidents, including damage and desecration, abusive behavior, and violent attacks. The phrase Jews are evil had been painted in large letters on the walls of a London Underground station. A London man’s car had been daubed with a swastika and the words Kill all Jews.

My working title was The Hate Artist. The first, horribly over-written sentence read: “I am not an angry man, not any more, at least. But the world is a hate-filled place, now more than ever, red and seething, alive with hidden fangs and horns, scaly surfaces and molten depths, charred carapaces, the malevolent glint of gold.”

Over the next few years, however, nearly everything I thought I knew about the novel changed. I made the main character an American Jewish woman, Esther, not a British man. I scrapped the first person narration and replaced it with a third person narrative from multiple points of view. I cut the references to the art of hate.

In my novel, Underground Fugue, anti-Semitism stands in counterpoint to the anti-Islamic sentiment that has arisen in the wake of multiple terrorist attacks, the War on Terror, waves of migration, and the European refugee crisis. On her deathbed, Esther’s mother, Lonia, remembers her escape from Czechoslovakia and Poland in 1939, while her elderly British friends fret over the anti-Semitic climate of London in 2005. Meanwhile, as the 7/7 terrorist bombings on the London Tube draw near, Esther begins to suspect that the boy next door may be involved in radical Islam. The novel asks, How does fear drive us to betray the ones we love? The question of what it means to be hated is less important than the question of what it means to hate.

As always, writing is an act of discovery. Writing this novel made me reconsider how my sense of self has been shaped. The old story of Jewish persecution has been replaced by the more complicated question of how we act on the legacy of that history we carry with us to challenges of the present day.

Margot Singer is the author of a novel, Underground Fugue, and a linked short story collection, The Pale of Settlement. She is also the co-author, with Nicole Walker, of Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction. She is the recipient of the Flannery O’Connor Award, the Edward Lewis Wallant Award, the Reform Judaism Prize, the Glasgow Prize, the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, as well as grants from the NEA and the Ohio Arts Council. She is a professor of creative writing at Denison University in Granville, Ohio.