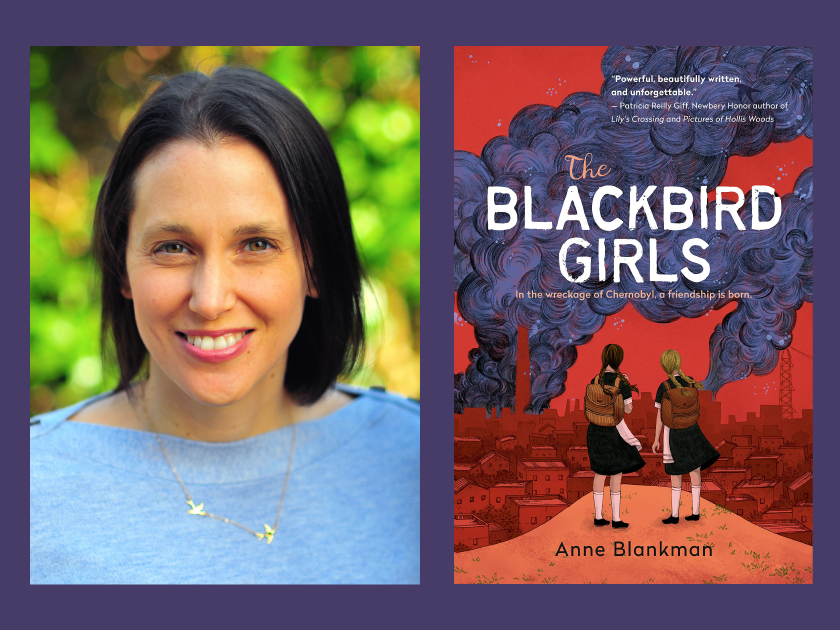

Anne Blankman’s most recent novel, The Blackbird Girls, was awarded the Sydney Taylor Silver Medal in the Middle Grade category, and the National Jewish Book Award in Middle Grade Literature. In a conversation with Emily Schneider, Blankman discussed her writing process, the personal and historical origins of her story, and its points of contact with questions of Jewish identity.

Emily Schneider: The Blackbird Girls could have been a different book; it is a story about the impact of the Chernobyl disaster on two families in 1980s Ukraine, one Jewish and one not. Why did you choose to weave together this narrative with the alternating one set during the Holocaust in Kiev?

Anne Blankman: Great question! My idea for The Blackbird Girls first came to me when I was in ninth grade and met a new classmate named Victoria. She had recently moved to the United States from Ukraine. Victoria was one of the smartest, fastest-talking girls I’d ever met, and we clicked straightaway.

When we grew closer, Victoria told me that she had survived the Chernobyl disaster.

In order to keep Victoria safe, her parents gave their six-year-old daughter the only plane ticket they could get and sent her alone to live with distant relatives in Uzbekistan. Forty-five years earlier, Victoria’s hosts — along with scores of other Ukrainian Jews — had fled from the approaching German army and wound up in the southern Soviet provinces.

These two journeys — one to run from invading soldiers, one to escape nuclear fallout — have haunted me. I knew I had to write a story combining the two, showing how the past echoes in the present.

ES: This is an ambitious novel; you’ve integrated several different themes without them competing for dominance. There’s antisemitism, family trauma, the cognitive dissonance caused by living in a totalitarian society, and also child abuse. Was it hard to maintain control over the writing process?

AB: Weaving together different themes was an organic process. When I drafted The Blackbird Girls, I focused on getting the story out of my head and onto paper. With each revision, the characters’ arcs and the story’s themes grew clearer.

My wonderful editors at Viking Children’s Books, Kendra Levin and Maggie Rosenthal, provided valuable support. During one round of revisions, Kendra reminded me that “trauma doesn’t suddenly stop.” Her advice helped me figure out how to chart Oksana’s emotional response to abuse, from fear to anger to empowerment.

ES: The Blackbird Girls really stands out for confronting the ugly truth about the persistent hatred of Jews in Eastern Europe post-Holocaust. Oksana’s father tells her that Jews are liars and parasites. School bullies tell Valentina to “go back to Jerusalem.” Did you consider the knowledge gap, and maybe the surprise, of some readers in confronting this fact? This is a book where the victims are also victimizers, not a comfortable truth.

AB: Yes, and let me be clear: many survivors of abuse do not become abusers themselves.

As I began constructing Oksana’s character, I asked myself: How does bullying start in the first place? What triggers that behavior?

Asking those questions forced me to confront my own experiences with bullying. When I started attending a new school in third grade, a classmate decided I would become her next target. She called me names, made fun of me for being tall, and chased me on the playground. At the time, I thought she was the most horrible person in the world. Years later, she reached out to me on Facebook, and I learned she had endured significant childhood trauma. Suddenly, her behavior in third grade made sense. Her bullying masked pain.

ES: You had a rare opportunity for closure. Your readers must relate to Valentina’s victimization. But they might also relate to the protective nurturing of an older character. Rita/Rifka, Valentina’s grandmother, is a major figure. She rescues her own family as well as Oksana after the Chernobyl disaster, and she herself was rescued from the Nazis. She is a powerful character; how did you create her?

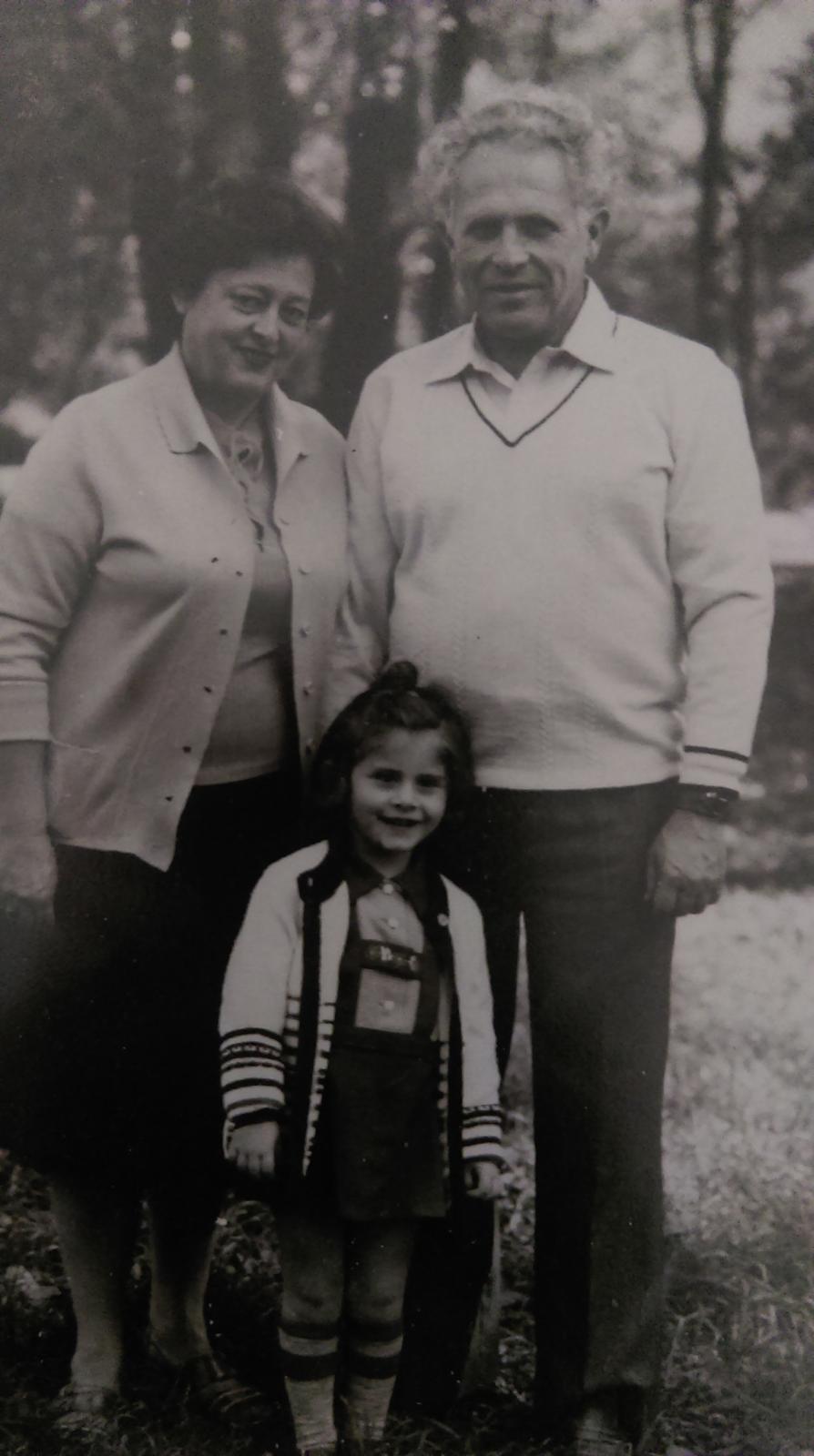

Victoria pictured with her grandparents, Valentina and Yefim, shortly before the Chernoybl disaster. Courtesy of the author

AB: My former classmate Victoria, who survived the Chernobyl disaster, is still one of my dearest friends today. When I asked her permission to write a story inspired by her experiences, she not only said yes, but she and her grandparents graciously allowed me to interview them numerous times. Valentina and Yefim, Victoria’s grandparents, are in their nineties and are two of the strongest people I’ve ever known.

During World War II, Yefim was a teenager. Like Rita/Rifka, he managed to escape Kiev before the German army surrounded it. Because most of the railroad tracks had been bombed, he walked across Ukraine. He slept in forests, ran from Ukrainian farmers who wanted to turn him over to the Germans, and scavenged for food anywhere he could. One night, he huddled on a barge gliding down the Dnieper River while German bombs exploded all around him. Miraculously, he survived and made it to safety in Uzbekistan. After the war, he returned to Kiev to find that most of his family had been murdered at Babi Yar.

Despite the horrors he experienced during the war, Yefim managed to make a life for himself. He married Valentina, Victoria’s grandmother. Together they had a daughter and found jobs they enjoyed. When they were in their sixties and the Soviet Union collapsed, they applied to live in the United States. They wanted their granddaughter to be able to live as a Jew without fear.

Yefim’s courage and resilience and Valentina’s straightforward, loving demeanor inspired me to create Rita/Rifka. I’m fortunate to know Yefim and Valentina, and I hope I did them proud.

ES: Returning to the theme of child abuse — this is a topic that used to be forbidden in children’s books, but is now much more common. The taboo may have been removed, but it’s still so difficult to discuss honestly while avoiding any sense of exploitation. What was it like for you to write these scenes?

AB: Those scenes were the hardest to write. My editor and I felt it was important to depict the abuse Oksana experiences. Having those parts occur “off page” could have suggested there was something secret or shameful about Oksana’s trauma. In order to prevent myself from veering into exploitative territory, I knew I had to write those scenes as truthfully as I could.

My emotions were already raw when I drafted the scenes of abuse. My husband had been just been diagnosed with stage III cancer. It was a terrible shock — he was only in his thirties and had always been healthy. One day he felt strange; five days later, doctors found a ten-centimeter-wide malignant tumor. Our daughter was in third grade, old enough to understand the gravity of her dad’s diagnosis. I was working full-time as a school librarian and drafting this book in the evenings.

My husband’s health made me feel close to Oksana. Like her, I felt sorrow and anger, combined with the determination to keep going, no matter what. When I sat down to write about Oksana’s abuse, I poured my feelings of grief and love into her. (I’d like to add that my husband is now cancer free).

These two journeys — one to run from invading soldiers, one to escape nuclear fallout — have haunted me. I knew I had to write a story combining the two, showing how the past echoes in the present.

ES: The family experience you’ve shared sheds light on the sensitivity with which you draw your characters. In The Blackbird Girls, no one can expect to hear the truth. I used the term “cognitive dissonance” in referring to life in the former Soviet Union. The Chernobyl workers, for example, are told that, in the rare case of radiation poisoning, “all you had to do was drink milk or mineral water and eat plenty of cucumbers, and you’d be well in a day or two.” Later, when Valentina and Oksana are in Leningrad, you convey the sinister, daily secrecy needed to survive in that city. Was it difficult to construct this kind of dystopia for readers who might be used to reading the fictional variety?

AB: Oddly enough, no! I didn’t have to construct my own dystopian world, like a fantasy or science fiction writer does. Instead, I had incredible, real-life details of what it was like to live in a totalitarian state.

For me, the greatest difficulty was deciding which facts to incorporate into my story and which to leave out. In my research, I come across so much fascinating information. Most of it didn’t make the final cut. It might be something my characters wouldn’t know or something that wouldn’t enlighten my readers. Only information that propels the story can stay.

ES: I would guess that many of your readers will be surprised that Rita/Rifka is saved by finding shelter with a Muslim family in Uzbekistan. Could you tell me why you decided to incorporate this part of history into her story?

AB: When I interviewed Victoria’s grandparents about their experiences during World War II, I was struck by how many times they found help from unexpected sources. Several of Yefim’s relatives found refuge in Uzbekistan, where they were welcomed by members of the Muslim community. Although all religions were discouraged under Soviet rule, there’s no question that Jews and Muslims were persecuted the most severely. According to Yefim’s stories, their common suffering helped them to understand and help one another.

ES: The Blackbird Girls is primarily focused on female characters. They aren’t paragons of virtue; most are strong, but Oksana’s mother is both weak and destructive. Why did you choose to center the book around women?

AB: The decision felt like a natural one. Men, not women, worked at the Chernobyl nuclear power. Men, not women, fought in the Red Army during World War II. It was women and children who were left behind to pick up the pieces. I wanted to explore how females, young and old, found the inner strength to go on.

ES: How do you see The Blackbird Girls as an exploration of Jewish identity?

AB: You’re the first person who has asked me this question, and I’m glad you did! I think of Valentina’s religious experiences in The Blackbird Girls as a journey of “Jewish discovery.” Like most Soviet Jews in the 1980s, Valentina has been raised without religion. She’s never been inside a synagogue or celebrated a Jewish holiday. Initially, her Jewish identity is a hindrance, for it makes her a target for bullies at school. She also knows it means she’ll need extremely high marks to get into university or to hold a good job. For Valentina, her Jewish identity has nothing to do with religion and everything to do with her background.

After the Chernobyl explosion, she escapes to Leningrad and stays with her grandmother, who introduces her to some of the basic tenets of Judaism. For the first time, she celebrates Shabbat. Judaism becomes a source of comfort for her, as well as a connection to her dead father. It’s more than her background; it’s her religion and her culture.

While I wrote The Blackbird Girls, I experienced my own religious journey. As I already mentioned, my husband had been diagnosed with cancer. The initial tests looked dire, and we didn’t know if he would survive. While he had more tests and we waited for doctors to come up with a treatment plan, we felt heartsick. But the whole time, I felt as though I stood upon rock-solid ground. In my heart, I knew it was Judaism that kept me steady.

This is part of the Sydney Taylor Blog tour. Click here for the full schedule.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.