This piece is part of our Witnessing series, which shares pieces from Israeli authors and authors in Israel, as well as the experiences of Jewish writers around the globe in the aftermath of October 7th.

It is critical to understand history not just through the books that will be written later, but also through the first-hand testimonies and real-time accounting of events as they occur. At Jewish Book Council, we understand the value of these written testimonials and of sharing these individual experiences. It’s more important now than ever to give space to these voices and narratives.

In collaboration with the Jewish Book Council, JBI is recording writers’ first-hand accounts, as shared with and published by JBC, to increase the accessibility of these accounts for individuals who are blind, have low vision or are print disabled.

I almost didn’t see my first stolperstein; I nearly stumbled by it. In fact, I was so blind to the little memorial plaques that it was a colleague, a fellow Israeli, who first pointed out the little brass squares on the cobblestoned streets of Cologne, Germany. I remember how we stopped and stood in a semicircle around the plaques, watching and listening as our colleague crouched down and showed us the basics – a name, deportiret (deported), a date, Auschwitz.

Ever since that evening twelve years ago, whenever I am in Europe, I find myself searching for stolpersteine while walking down the street. I stop whenever I see one, always feeling an obligation to read the names.

I see stolpersteine as a mix of historical documentation and atonement, a memorial and a piece of art. I realize that these encounters with stolpersteine reflect the experiences of an outsider, a woman born two generations after the Holocaust, whose great-grandparents fled Europe before World War II. I don’t know how I would feel if I encountered stolpersteine with the names of my relatives who didn’t make it. I also don’t know how I would feel if I moved to a city and had to face these symbols every day. Whatever the case, I have a feeling that, at some point, the stolpersteine would become almost invisible, blending in with the rest of the scenery.

I am thinking about stolpersteine a lot these days in the weeks before Yom HaZikaron. In the last six months, I’ve had my share of stolperstein moments, not in the form of plaques with the names of Holocaust victims, but as stickers commemorating the fallen soldiers and terror victims after October 7.

The analogy of stickers to stolpersteine is far from perfect. Memorial stickers don’t follow a standard template, size, shape, or color, and instead of a single brass plaque, there can be hundreds of copies and several designs commemorating the same person. But there are similarities between them, beyond the obvious fact they both include basic biographical data about those being honored. These stickers – like stolperstein– appear in the public space, where we encounter them by chance, and create a giant decentralized memorial.

______

I didn’t stumble onto my first memorial sticker. It was given to me by a teenager, a cousin of Lavi Lipshitz, at the end of the shloshim ceremony in Har Herzl. Lavi, who was killed in battle in late October, was one of my son Ben’s closest friends. I had known Lavi since he was a toddler.

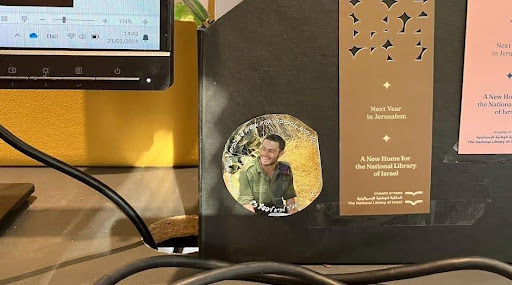

I admit that, at first, I didn’t quite know what to do with the sticker. After feeling guilty that it stayed in a drawer, I decided to paste it on my laptop. It sat next to the decorative stickers with my company’s logo that I had gotten as swag when I first joined. But I regretted my decision when we went back to the office; in my first team meeting, I felt the stares on the back of my laptop screen. When I returned to my desk, I removed Lavi’s sticker and pasted it on an organizer, where it remains to this day— his smile still fresh, even if as the tired adhesive has begun to fail, and the curling partly hides the words around the sticker’s perimeter: “Care for the environment, care for each other, for all living beings… Do, always.” In memory of Staff Sgt. Lavi Lipshitz Z”L.

All photos courtesy of the author

Stickers in the public space aren’t an anomaly in Israel — after all, this is the land of “Shirat Ha Stickerim,” the hip-hop hit from the early 2000s whose rhyming lyrics were quotes from dozens of bumper stickers juxtaposed against each other. After a few years of apparent calm — or too many election rounds — stickers again became ubiquitous in last year’s protests against the judicial reform. Memorial stickers aren’t a new phenomenon either; I remember seeing a few of them in previous years on benches and in gardens. But the sheer variety and the extent of the memorial stickers during the current war, has turned them into an entirely different category of commemoration.

One sticker spotted on the windshield of a parked car shows a smiling woman against a peach-colored background. Fonts with radiating lines, like a child’s drawing of the sun, say “Gili, the sunshine in our lives. October 7th 2023.”

On a lamppost, from left to right I see a blond soldier in a red beret, saluting, with the words, “Do Good. #Be_Like_Shahar. In memory of Shahar Friedman.”

At the waiting room of my dentist, leaning against the decorative lamp, the back liner intact, I see a sticker that says: “Be like Moti. Just do it. In memory of Maj. Moti Shamir, who fell in the battle to defend Kibbutz Reim, October 7th, 2023.”

And on the gray plexiglass of a bus stop in Jerusalem, I notice a sticker that says: “Smiling is our strength, not just a catchphrase. In memory of Uriah Aymelek Goshen, January 17th 2024.”

______

I can’t remember what first made me take out my phone and snap pictures of the stickers. Maybe it was curiosity, maybe it was a sense of duty to capture it, and later, try to learn more about the person. Or maybe it was simply the realization that paper is, like life itself, impermanent. That all stickers, with or without protective coating, will eventually scuff, fade, disintegrate.

What I do know is that once I started photographing them, I couldn’t stop. I began actively seeking them out, allowing more time to wander around Tel Aviv and Jerusalem in train stations and bus stops, on sidewalks and plazas. I looked for them as I parked my car, on my way to my office in Rehovot, in my hometown of Modiin, a relatively young city that, given its demographics, has one of the highest ratios of combat soldiers in Israel.

One morning in February 2024, as I opened the zipper of my backpack to get it ready for inspection at the entrance to the local mall, the sticker on the booth where the guard sat caught my eye. I took a step back, wanting to get a better look, letting those in line behind me take my spot.

The sticker was of Captain Ori Shani, a name that didn’t just seem familiar from the news, but from the way Ben, my son, had described him: “A really great guy.” Ori was a Golani platoon commander stationed at the military outpost in Kibbutz Kissufim, less than a kilometer from the Gaza border. Ben had been spending a few days in Kissufim as part of his training and met Ori there on the eve of Simchat Torah.

After fourteen grueling hours on October 7, Ben was one of dozens of soldiers and civilians lucky to make it out alive out of the Kissufim post. It was only a week later, in the chaos of the first days of the war, that Ben learned that Ori had been amongst those killed.

“Good will triumph!” Read the sticker in bold white letters, Ori’s gaze smiling at someone off camera.

My own smile faded. Yes, but at what price? I wondered.

______

When I first started seeing the stickers in public spaces, they were loners. A few weeks later, they almost always appeared in clusters, the presence of one serving as a magnet for others. Days after noticing the sticker of Ori Shani at the mall, a new one appeared below it. Over a dark pink background, was a woman with a perfect smile, her eyes almost closed. Words accompanied the image, “Your song [in Hebrew, Shir] will never stop playing. In memory of Captain Shir Eilat.” A Google search taught me she had been a commander in the lookout unit in Nahal Oz. She had lived in a moshav not far from the city.

The next time I was at the mall, there was a third sticker outside the booth, this time for a soldier who had been a resident of the city: “Focus on the here and now, enjoy the moment. In memory of First Sergeant Amit Most.” Ben had also mentioned Amit’s name; he was a friend of a friend.

A few weeks ago, I created an online album with the memorial stickers I was photographing, in an attempt to add some order and ensure I didn’t run out of storage on my phone. I then tried to create a small catalog, a spreadsheet with a photo of each sticker, and the data it contained: a name, a slogan, a date, and any links or hashtags. But after a handful of entries, I gave up, realizing that the project would require much longer than an evening in front of my laptop. At last count, I had more than 300 stickers, give or take a few repeats.

The few rows of the spreadsheet that I had filled revealed something else. Many of them, especially the ones I had photographed over the last month, had URLs or QR codes that pointed to a website or to a YouTube channel. Others featured an Instagram logo, and accounts that all began with the word remember, an underscore, and a name — Remember_Nati, Remember_Eden, Remember_Inbar_Hayman. A quick Instagram search then showed more than fifty accounts following this same formula, including one entitled Remember_Jonathan_Savitsky. Ben didn’t know him personally, but knew of him. He was a twenty-one-year-old from my city, who fell on October 7 after his unit was sent to support those stranded in Kissufim.

Looking at the posts and stories, another pattern becomes apparent. In addition to nostalgic photos posted by friends, or photos of different memorial ceremonies, there are photos of the memorial stickers taken across the country. The accounts even cross-tag each other, especially if the photo also contains someone else’s memorial sticker and adds the relevant name. Using hashtags, naming conventions, and tagging, the administrators behind these separate accounts are creating a virtual, decentralized memorial and community.

Last month, a friend who stopped for coffee at the Beit Kama intersection near the Gaza Envelope sent me a photo of a wall full of stickers. Since then, I’ve noticed more of these memorial walls —on a pedestrian bridge, in the Hashalom train station, outside the IDF headquarters in Tel Aviv. In a way, this seems to me to be coming full circle, transforming a decentralized sticker memorial into a more traditional type of memorial.

The record for the biggest number of stickers in a single place, as far as I can tell, belongs to the booth at the checkpoint of Road 90, just north of the Dead Sea: more than fifty. When I asked the soldier on duty how that came to be, she said that families driving past often just roll down their windows and hand them a sticker, asking to please add it to the collection. She told me that it happens quite often.

Several weeks ago, I again stopped for the inspection of my bag outside the mall. I turned around and realized that the three stickers of Ori, Shir, and Amit were gone.

I wondered, Who hasdared to do this? A guard at the end of his shift? The management office of the mall? Cleaning crews from City Hall? Whoever was responsible, they hadn’t even done a thorough job. Left behind were crusty remnants of adhesive in the size and shape of the original stickers.

It’s safe to assume that one day, maybe even by next year’s Yom HaZikaron, the colors on the memorial stickers will fade, and the benches and bus stops will be repainted. The stickers will disappear from our collective spaces (even if they remain in our collective memory.)

One day, hopefully much sooner, this nameless war will end, and we will stop obsessing about the slogans and the smiling photos frozen in narrow strips of self-adhesive substrate. This won’t mean, God forbid, that we have forgotten our dead. Quite the contrary. It will mean that, in their memory, we are building something more permanent: a country that doesn’t feel like it’s teetering on the edge, about to be torn off by the wind.

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author, based on their observations and experiences.

Support the work of Jewish Book Council and become a member today.

Vivian Cohen-Leisorek is a Guatemalan-Israeli writer whose work has appeared in The Tel Aviv Review of Books, BusinessWeek Online, and Underground, and publishes a popular Substack diary about the October 7 War. She currently working on a memoir about her year volunteering with injured soldiers in Israel’s largest hospital.