Kościuszko Square (Rynek Kościuszki) and Old Town Hall (Ratusz) in Białystok, Photo by Scotch Mist via WikiMedia Commons

A year ago, on the last sunny day of September, I caught the morning train from Warsaw to Bialystok. I had lunch plans with my friend Magda, but that was pretense. I was writing a book about Polish baking and needed to confirm what I already knew: that there are no bialys in Bialystok. We all know why. One final check before I handed in the manuscript.

Either the train got in early that day or Magda showed up late so I sat on a bench and watched people hurry in and out of the classical-style train station. Long before Bialystok became the edge of a certain kind of Europe, after which Lukashenko’s Belarus and then Putin’s Russia begin, the station was once an important stop on the Russian Empire’s Warsaw – St. Petersburg line. Burned down in the First World War and bombed in the Second, the city kept rebuilding the train station to look just as it had before. This means you can get a pretty good idea of how grand things were back in the day, so long as your imagination allows for kebab shops and Zabka convenience stores. I’d been out in Warsaw all night and my aching head allowed for no such anachronisms.

I’d been doing this sort of food research trip all year but aside from writing about it, it was no different than what I’d been doing for a decade and a half. I live in Berlin but don’t like it very much. With the exception of its parties, Berlin isn’t a place to feel warmth and welcome as a stranger. But Poland is right over the border offering relief. In Poland, I’ve always been able to find a cheese blintz at a roadside stand or a loaf of challah at a bakery or a plate of kasha at a milk bar. Restaurants smell like home did on days when we made chicken soup. Is everyone just friendlier? Projection is a tremendous thing.

When a smiling Magda rescued me from my bench, the repercussions of the previous night had spread to my stomach. I needed to eat. She took me by the elbow. I was with the right person; Magda works for Warsaw’s Polin Museum and is an expert on Jewish food in Poland. We’d first stop at a bakery – it was plum and streusel bun season – and then she’d take me for lunch.

Magda walked me past restaurants advertising kishke and potato kugel – regional specialties to this day – and popped into a grocery store selling herring “Jewish style.” We passed an abandoned Jewish girls school and strolled by ice cream carts in the Park Palacowy Branickich.

Fourteen types of herring, Photos courtesy of the author

Just across from the palace park is the Pawilon Towarzyski. It’s a midcentury semi-circular building that’s been there since 1973. The unusual shape and copious glass means the sunlight comes in at every hour of the day, even in the winter despite the Middle European haze. The restaurant changed owners and modernized a few years ago so the flatware is contemporary and there are on-trend light fixtures.

Magda and I ordered barszcz and chopped herring on toast points and then she got a call from work. She excused herself to take it. No longer facing her, I had a clear view to the end of the restaurant.

Against the opposite wall sat a perfectly bald elderly man with a face like a parrot. He wore a fine navy suit and a pressed white shirt accessorized with tie, gold clip, pocket square, and cufflinks. A waiter came and laid the man’s table with pressed white linen and a heavy cloth napkin and silverware in the old style. I looked around at the rest of us chumps being served straight onto laminate. What the hell was going on? The waiter then set down a plate of soup on the old man’s tablecloth. I stared while he slurped. The longer I watched, the more uncanny it became. My head throbbed. Where was my barszcz? This man was a dead ringer for the Singer brothers.

The thing is, all those years I’d been digging through Poland for familiar foods, I’d also been directing my travels through the writing of I.J. and I.B. Singer. There are hardly better guides if you want to look for something you’re missing in worlds that no longer exist. The Magician of Lublin saw me covered in ticks in a pine forest somewhere in the far East of Poland. Shosha got me chased out of a courtyard in the Praga district of Warsaw by an unleashed dog. The Brothers Ashkenazi had me shuffling through a February snow storm in Lodz.

Lately, deep research into Polish and Polish Jewish baking both in-situ and diaspora – cue Enemies, a Love Story and Shadows on the Hudson–had made the Singer brothers’ work all the more relevant for me. I write in my upcoming cookbook Dobre Dobre, that I. B. Singer “had a particular knack for describing and memorializing pre-war Poland— from bakers’ daughters flirting over yeasty baskets of rolls, to the smells and sounds, both foul and sensual, of Krochmalna Street, the chaotic heart of the Jewish ghetto, to the smoke-and schmalz-filled salons where artists and bundists met to argue over their vibrant, difficult world.”

I caught a waiter as she passed and asked what was going on. Why did that man have a full fine-dining setup? Who was he?

“He brings it from home,” she said, nonchalant. “It’s how we used to serve people. He insists on it. He’s been coming here since Pawilon opened.”

Magda returned from her call. I didn’t trust what I was seeing.

“Do you see this guy? Does he look like one of the Singer brothers to you?”

Magda agreed. Then her phone rang again.

I kept staring.

A journalist friend once told me a story from the 1980s. He was a college student when he saw Isaac Bashevis Singer on the street in New York. So he chased I.B. down the street to introduce himself. Mr. Singer, he told him, I’m a big fan of your work. Mr. Singer asked him his name, so he told him. Then Mr. Singer asked him what he did, and my friend told him he was a writer. At this point in the story I held my breath, horrified. The chutzpah. But Mr. Singer just called over his wife and introduced him. “He’s a reader and a writer,” Mr. Singer said. Imagine that. Isaac Bashevis Singer calling you a reader and a writer. I asked my friend how he could have dared. He’s one of us, he told me. Why not?

When the old man finished his lunch, a nurse who’d been hiding herself came out of nowhere to help him get to his feet. Now I saw he had alligator shoes and a polished wood cane. As he and the nurse passed, he stopped and smiled at me. Up close I could see the liver spots on his head. Up close he looked even more like a Singer.

“We know each other,” he said.

“I don’t understand Polish well, can you speak slower?” I said, my knowledge of another Slavic language helped me bumble through the phrase.

“We know each other,” he said, in English this time.

“Do we?”

“Where are you from?”

“I’m from America.”

“What do you do?”

I hesitated. “I’m a baker.”

“We know each other,” he repeated, still smiling.

“Of course we do,” I said. Why not?

Then his nurse took his arm and walked him away. Magda’s call was over. She laughed from across the table. We had to get going too.

There were no bialys in Bialystok that day and Magda hasn’t seen the old man at Pawilon since. No one in the city seems to know who he is. I’ve made inquiries. A lot of things go missing in that town; some things can be rebuilt to imitate what once was. Other things can’t. My book comes out in October. I’m glad I didn’t tell him I’m a writer.

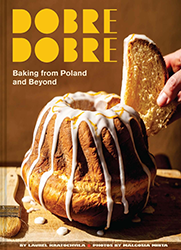

Dobre Dobre: Baking from Poland and Beyond by Laurel Kratochvila

Laurel Kratochvila is an American-born writer and baker based in Berlin and trained in France. She runs the iconic Fine Bagels bakery and the natural wine bar, Le Balto. Her first book, New European Baking, was a finalist for a James Beard award in 2023.