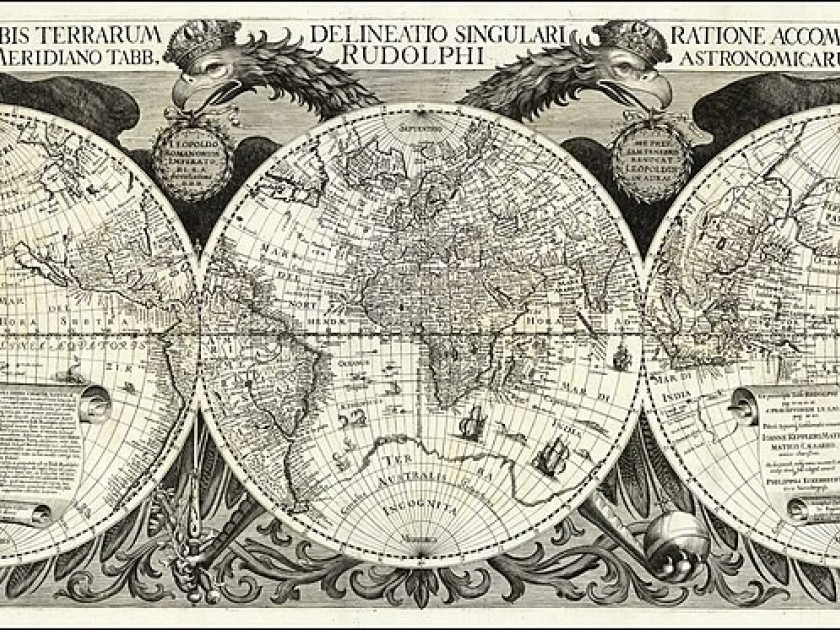

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Start by considering the ending. And consider the structure, too. As I wrote Because the World Is Round, a memoir about my family’s trip around the world in 1970, a sturdy narrative arc emerged. The story begins with the sale of our family automobile brake-repair business in Dallas, and the action rises and falls as we travel together — India, Afghanistan, Iran, Israel, Yugoslavia, Europe — and I explore my relationship with my mother, who was paralyzed by polio and used a wheelchair. The book concludes decades later, when my mother is dying, and I sit at her bedside, watch her sleep, and ponder the extraordinary life she has led. How fortunate I was to come upon a structure that could hold in place the mother-daughter story I wanted to tell.

But the more I wrote, the more I recognized that it was only the travel narrative — moving from place to place — that had a discernible beginning, middle, and end. The real story, the development of my unique interdependence with my mother, shifted shape and resisted the limitations of a clean narrative arc. Some memories of our trip deepened, and others lost significance altogether. Dancing on stage at the finale of Hair! in London was a fading fun fact of my life until it became emblematic of my newly liberated spirit. Pushing my mother up a loading-dock ramp to enter a Neiman Marcus seemed like a mundane part of shopping, until I realized how this lack of access was an assault on her dignity.

The process of writing taught me how the passage of time and the accumulation of new experiences allow for endlessly revealing interpretations of the past. Interpretations that don’t stop. Interpretations that circle and spin like the wheels of my mother’s chair. I learned that there was nothing static about the real story I longed to tell. There is no end to it. In fact, the story is that the story has no end. “So I am not going to stop here with a final period, as if this story has a neat finish,” I begin the final paragraph of the book, before closing the last page with a question mark.

And in the act of writing, I learned that there is no answer to the “how” of our relationship; there is only an ever-deepening description of our devotion and shared experiences. Today our relationship means this. Tomorrow, with new experience and insight, it means that. All of it is true.

Now imagine my surprise after I send my manuscript off to the publisher, and pick up Dara Horn’s then new People Love Dead Jews. Embedded in her essays about Jewish life and antisemitism is “Chapter Five: Fictional Dead Jews.” Here Horn examines the Western literary tradition, which strives for coherent and satisfying endings — ones where the protagonist is either saved or experiences an epiphany, a moment of grace. This is not the Jewish literary tradition, Horn argues. Stories in the Jewish canon, as she meticulously demonstrates, “actually didn’t have endings at all.” These are works without conclusions. They don’t offer us endings, but present us with beginnings, with ongoing searches for meaning. Jewish stories, she concludes, are about “the power of resilience and endurance to carry one through to that meaning.”

Had Dara Horn read my manuscript? No. Had I inadvertently stumbled my way into a deeply rooted Jewish tradition? No comment.

With my book, I set out to explore how my mother managed to raise a family, pursue a career, and travel the world from her wheelchair. I wondered what role I played in her success and how her disability affected my development. I discovered a narrative structure, and I wrote and wrote and wrote. And in the act of writing, I learned that there is no answer to the “how” of our relationship; there is only an ever-deepening description of our devotion and shared experiences. Today our relationship means this. Tomorrow, with new experience and insight, it means that. All of it is true. In other words: In writing a memoir that refuses to end, I align myself with a deeply ingrained Jewish point of view. I discover for myself that insight is infinite and meaning is endless.

So, I implore, embrace the spirit of Jewish storytelling. Consider the ending. Look at the structure. Then, ask questions. Push them until they multiply, then allow them to fade unanswered. Let your world spin like a wheel. Attach yourself to characters and laugh. Or cry. Or just stare into space. Enjoy a good Jewish story without (an) end—

Jane Saginaw is a student in the Ph.D. Program in Literature at the University of Texas at Dallas. Her memoir, Because the World is Round, recounts a family trip around the world in 1970 with her mother who was wheelchair-bound from polio. Before returning to graduate school, Jane was a trial lawyer with Baron and Budd in Dallas, Texas. She later served in the Clinton Administration as the Regional Administrator of the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region Six. In 2006, she was awarded Trail Lawyer of the Year by Trial Lawyers for Public Justice for her environmental work involving groundwater contamination in Tucson, Arizona. Jane’s undergraduate degree is in cultural geography from the University of California, Berkeley. Her law degree is from the University of Texas, Austin. Her essays and poetry have been published in Athenaeum Review and are forthcoming in Image, D Magazine, and PB Daily.