With my debut book, In Other Lifetimes All I’ve Lost Comes Back to Me, coming out this month, I’ve been receiving a lot of questions about the subjects of my stories: contemporary women experiencing longing and loneliness, and Jewish ghosts from the concentration camps. Some might wonder, is it a sacrilege to put these two together?

In response, I find myself thinking more and more about Day, by Elie Wiesel.

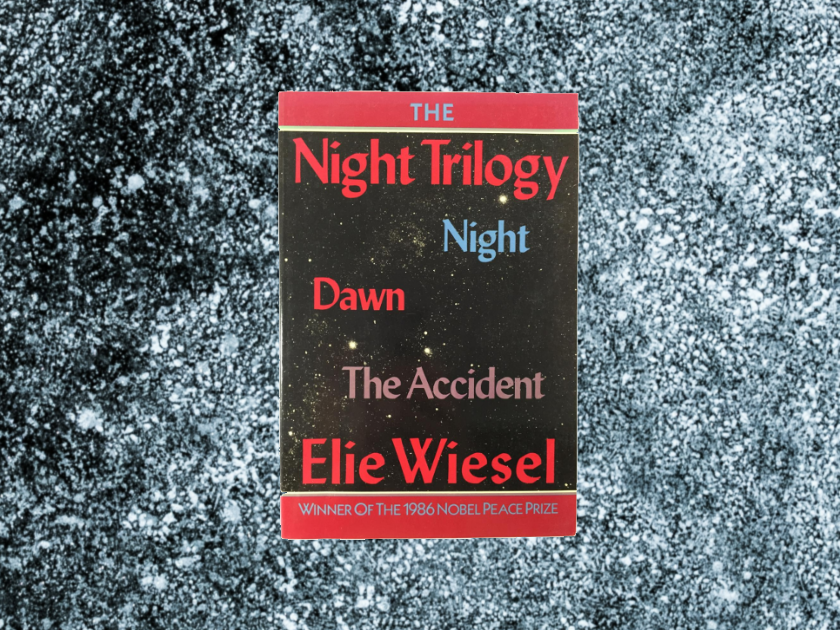

I discovered the book just before the pandemic, when I was living in New Hampshire as the writer-in-residence at Phillips Exeter Academy. I was walking through the library when I discovered something I couldn’t believe I didn’t already know: Elie Wiesel’s famous Night is part of a trilogy. Its counterparts of Dawn and Day, each slim books of about one-hundred pages.

I took them out immediately and was enthralled by Day, a work of immense power .

Day asks: how does the survivor of the camps ever view his body as a sexual site thereafter? Can the body be a source of pleasure after it was a source of so much pain?

Most notably, Day is all about lost women. The narrator is haunted by memories of his mother, his grandmother, women sexually exploited both in the camps and after. The narrator wonders if his own suffering can vicariously harm his current girlfriend, even once the camps are past. Night is about the boy and his father, but Day is about the women lost and in the narrator’s present.

Immediately upon reading Day, I felt that these were themes I could write into. There was a modern female perspective to be drawn out here. I wondered: What about the granddaughter of the survivor?

For me, this brought up the question of scale. How unequal in scale they were, the problems of dating in the modern age and the problems of the camps.

The question of scale is, in many ways, the undergirding drive of fiction. Fiction uses the personal to stand in for the universal. George Saunders posits that great literature is based in “perhaps the most radical idea of all: that every human being is worthy of attention and that the origins of every good and evil capability of the universe may be found by observing a single, even very humble, person and the turnings of his or her mind.”

Of course, the small problem of contemporary dating and the large problem of the camps are unequal. And they also coexist. Questions of aloneness, safety, and reproduction tangle the two together.

In Day, Wiesel presents the girlfriend character, Kathleen, as the narrator’s opposite. She thinks the universe is ultimately about love, and their love in particular. “For Kathleen, even God was not so much a subject for discussion as a way to bring the conversation back to us.” But the narrator knows that the universe has been taken away to heaven by train, and all that’s left is smoke. He tells himself that, in the aftermath, he will “have to learn…to love. You can learn anything.”

But the clear feeling in the narration is that, after the camps, such an education is impossible. “She wanted to make me happy no matter what,” he says. “To make me taste the pleasures of life.” But “[s]he liked life and love; I only thought of life and love with a strong feeling of shame.”

Thus, from the start of the novel, the paucity of romantic love in the face of suffering from the Holocaust is thematized. The entire book takes this as its central problem. A problem of scale, ultimately .

The narrator of Day struggles with the obligation of the living, who are walking around this earth after the trauma of the camps. Are the living obligated to the dead and to their memories, as the narrator seems to think? “I think if I were able to forget I would hate myself,” he says.

Or are we obligated to the living, as his friend and foil Gyula says, in this stunning passage at the book’s end: “Suffering is given to the living, not the dead.[…] If your suffering splashes those around you, […] then you must kill it, choke it. If the dead are its source, kill them again, as often as you must to cut out their tongues.”

Night was about the boy and his father, but Day is about the women lost and in the narrator’s present.

In this debate between the characters, I recognized a tension in my own work: what is the relationship between the living and the dead? Does that relationship pertain not only in our moments of reflection and solitude, our moments of remembrance at a cemetery — but also during our moments of romantic intimacy?

In my book, this tension has form in the ghosts that live over the shoulder and between the legs of a contemporary woman who is trying to date.

When Day was first published in America in 1962, the title was not translated literally from the French Le Jour. The English-language title was The Accident, a reference to the car crash that is the major inciting and philosophical incident of the book.

Perhaps “The Accident” is a stronger title for a standalone book. But perhaps too there was something frightening to the publisher about linking the book so obviously with Night, as its companion. Night is about the inhumanity of the camps inside the camps; Day is about the inhumanity of the camps that lives on in the taboo arena of sex in their aftermath.

I am reminded of the publication history of one of my favorite Primo Levi stories, “Quaestio de Centauris,” translated into English for the first time only eight years ago. The New Yorker fiction editor Deb Treisman speculated that it wasn’t translated earlier because “Levi’s editor, Italo Calvino, felt that it wouldn’t be appropriate for the author of an important Holocaust memoir to publish this type of “biological fiction,” or sci-fi, in his own name.”

And yet I read that story as a direct response to the Holocaust, very similar to Day in its themes; it is about reproduction everywhere, a new fecund Garden of Eden that is quickly despoiled.

There is obviously a discomfort with imagining the Holocaust survivor in the realm of sex.

Yet world-renowned sex therapist Esther Perel says that her parents survived the camps, and that they “came out of that experience wanting to[…]embrace vibrancy and vitality — in the mystical sense of the word, the erotic.”

These examples inspire me to think that my overwhelming question is not so sacrilegious, that it was always being asked. The question is: What about the body? What about sex and desire?

It is, I believe, a question that deserves a literary response.

Courtney Sender’s writing has appeared in the New York Times’ Modern Love, the Atlantic, the Kenyon Review, American Short Fiction, and Tin House, among others. A MacDowell and Yaddo fellow, she holds an MFA from the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars and an MTS from Harvard Divinity School. She currently lives in the Boston area.