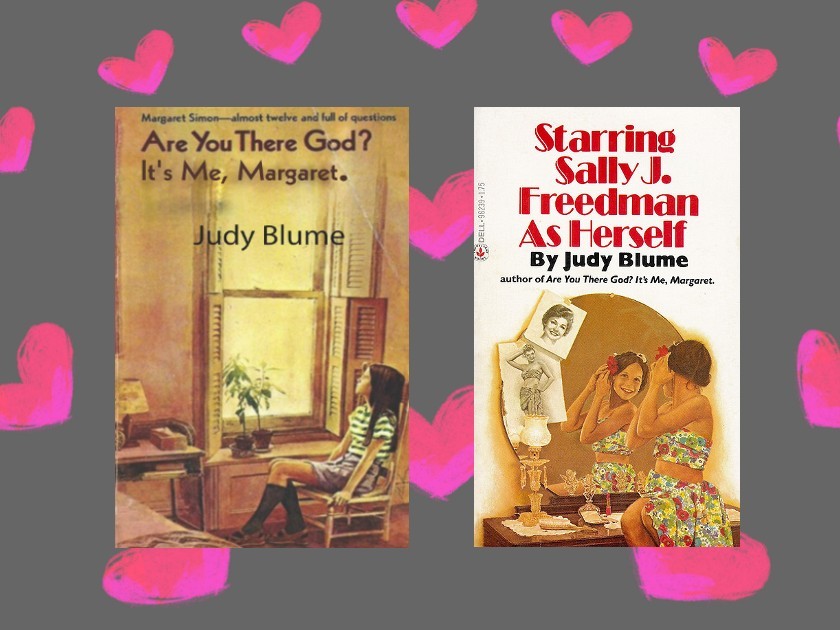

Eleven-year-old Margaret Simon is the protagonist of Are You There, God? It’s Me Margaret., by Judy Blume. Margaret is the daughter of an interfaith marriage. When her estranged Christian grandparents visit, there is a tense exchange with Margaret’s Jewish father over their granddaughter’s religious identity, which they claim is Christian. Her father furiously retorts that “Margaret is nothing!” ignoring his daughter’s confusion and pain about who she is which is so central to the novel. When the book appeared in 1970, interfaith marriage was increasing dramatically and made Margaret’s family situation notably relevant. However, Blume’s novel was mainly celebrated for Margaret’s frank, one-sided conversations with God, and the author’s feminist approach to acknowledging the physical and emotional aspects of puberty. Her Jewish identity seemed overshadowed by other issues.

Seven years later, Blume would introduce a very different character searching for self-definition in Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself, her most autobiographical children’s book. Sally’s family isn’t traditionally observant (like many American Jews of the early postwar period), but close-knit family relationships and the recent tragedy of the Holocaust indelibly mark her as Jewish. Both novels and characters imply tension between religious and cultural ways of being Jewish, but that divide takes on a different dimension in each of these coming-of- age stories. Although there are only seven years between the two novels’ publication, their settings are twenty years apart; much had changed in Jewish American life during that time.

Barbara and Herb Simon, Margaret’s non-Jewish mother and Jewish father, have each rejected their religious traditions; Margaret is afraid that she is “nothing.” Her question to God, “I can’t go on being nothing forever, can I?” is not a defiant challenge, but an anguished plea to fill a sense of emptiness. Today, children’s books about religiously hybrid families often reflect acceptance, featuring multicultural celebrations which validate both parents’ backgrounds. Back in 1970, Margaret had no such luck. Religious affiliation in her New Jersey community boils down to a choice of membership in the YMCA or the JCC. When her teacher asks students to fill out a questionnaire, Margaret completes the prompt “I hate” with “pimples, baked potatoes, when my mother’s mad and religious holidays.”

Margaret has only one connection to Jewish life, her grandmother, Sylvia. This Jewish matriarch does not force feed chicken soup to her family or whine about her son’s neglect. Instead, she has chosen to make peace with Herb’s decision to intermarry. Unlike Barbara’s parents, who disown her, Sylvia decides to adopt a pragmatic approach as a parent and grandmother, hoping to ensure Jewish continuity through unconditional love. She is a stark contrast to Margaret’s maternal grandparents, two-dimensional symbols of judgmental prejudice.

We celebrate Judy Blume for her bold challenges to repressive standards of expression about female experience, but two of her creations, Margaret and Sally, also embody the complex question of what it has meant to be Jewish in America.

Yet Sylvia is only a tenuous Jewish role model. She brings deli food from the city to the Simon’s New Jersey home, and inquires if Margaret’s nonexistent boyfriends are Jewish, but these routines seem disconnected from the focus of Margaret’s search. As part of her decision to ask God for guidance, Margaret delights her grandmother by asking to accompany her to services on Rosh Hashanah. This brief exposure to Judaism feels shallow, no different from the Presbyterian service she later attends with a friend. Both are marked by organ music and quiet decorum. Even the rabbi’s welcoming Margaret with “Good Yom Tov…It means Happy New Year,” feels perfunctory; the phrase is a generic holiday greeting, not the “Shanah Tovah” used on the New Year.

Margaret talks to God but the cultural aspects of Judaism which her grandmother represents are not part of the conversation. Blume, herself the product of a culturally Jewish but largely secular background, pointedly comments on the distance between these two aspects of being Jewish. She makes the most distinct religious event in the novel the Catholic sacrament of confession. Margaret taunts her classmate, Laura, by repeating nasty rumors about her, and then, while attempting to apologize, follows Laura to her Catholic church. Panicked by her own cruelty, Margaret enters a confessional. When the priest addresses her as “my child,” she says she is sorry and runs away. Laura has a clear advantage over Margaret, in her access to a ritual where a paternal figure offers solace. In contrast, Herb and Barbara’s desire to protect Margaret from the tribalism which has driven their families apart, leaves Margaret feeling disconnected.

Many of Blume’s readers, both in 1970 and today, undoubtedly share her secular background. The historical setting of that secular identity, however, has changed. Blume based Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself on her own childhood, growing up after World War II as the daughter of two Jewish parents. Like Margaret, Sally is navigating the unknown territory of young adulthood and trying to picture her own future. However, unlike Margaret, this ten-year-old girl plays a featured role in cinematically imagined scenarios, in which Sally rescues relatives lost in the Holocaust, or allows them to survive by defending themselves.

Sally worries about her personhood as much as Margaret, but her fears have a different context. Her beloved grandmother, Ma Fanny, is grieving for relatives left behind in Europe. Unlike the assimilated and culturally sophisticated Sylvia, Fanny is vulnerable and harbors old-world superstitions. Yet those qualities also provide Sally with a strong link to who she is and to what the Jewish people have lost. Sally shares her fears about family members’ fragile health with a Jewish school friend whose own father was killed in the Pacific.

Blume avoids sentimentalizing the devastating losses which inevitably affect Sally and other American Jews in the late 1940s, and which are absent from Margaret Simon’s life. Sally’s age-appropriate lack of self-consciousness allows Blume to push boundaries in scenes that are strikingly funny, even when dead relatives and Hitler make appearances. Since the recent catastrophe in Jewish life has lodged itself in her imagination, Sally and her friends play “Concentration Camp,” with Sally assuring the other girls that “nobody has to be Hitler because he is away on business.” She daydreams about her cousin Lila, who had actually been murdered by the Nazis. In the dream, Hitler is enticed by Lila’s sweet-smelling perfume, but Lila “whips her pistol out of her pocket, points it at Hitler’s gut and says, From all of us on the other side.” There is no tentative searching for Jewish identity here; unlike Margaret, Sally incorporates history into her other – more personal – anxieties. Instead of being murdered, Jews avenge their losses and reverse history.

Traditional religious observance is less important than cultural identity, both in Sally’s Florida community and in Margaret’s 1960s suburban world. The one Orthodox family in the Freedman’s apartment complex turns out to be judgmental and punitive, sitting shiva when their teenaged daughter becomes pregnant in a relationship with a non-Jew. Sally’s gentle and tolerant grandmother is the voice of humane Jewish values, telling Sally how shameful it is to equate a child’s mistake with death.

Margaret Simon and Sally J. Freedman are two Jewish girls in search of their place in the world. Their Jewish identity, Sally’s unmistakable and Margaret’s tentative, reflect changing times. In 1947, when Starring Sally J. Freedman begins, the continuity of Jewish life in America was still largely a shared assumption, even among those who defined themselves as Jewish more by culture and history than by faith and observance. By the 1960s, most Jews were more fully assimilated Americans; Jewish identity was becoming more flexible and pluralistic, but also more tenuous. Eating deli food and belonging to the “Y,” as Margaret Simon knew, no longer guaranteed the secure identity that Sally, for all her anxieties, took for granted. When Margaret asks God, “Why do I only feel you when I’m alone?” we can, perhaps, extrapolate that she is intuiting that Jewish life is rooted in community, a premise which her parents have rejected based on their familial predicament. Her mother’s bland assurance that “God is a nice idea” is functionally useless. Sally explores questions about death and survival in a Jewish context: unorthodox, inconsistent, and yet grounded in her family’s history. We celebrate Judy Blume for her bold challenges to repressive standards of expression about female experience, but two of her creations, Margaret and Sally, also embody the complex question of what it has meant to be Jewish in America.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.