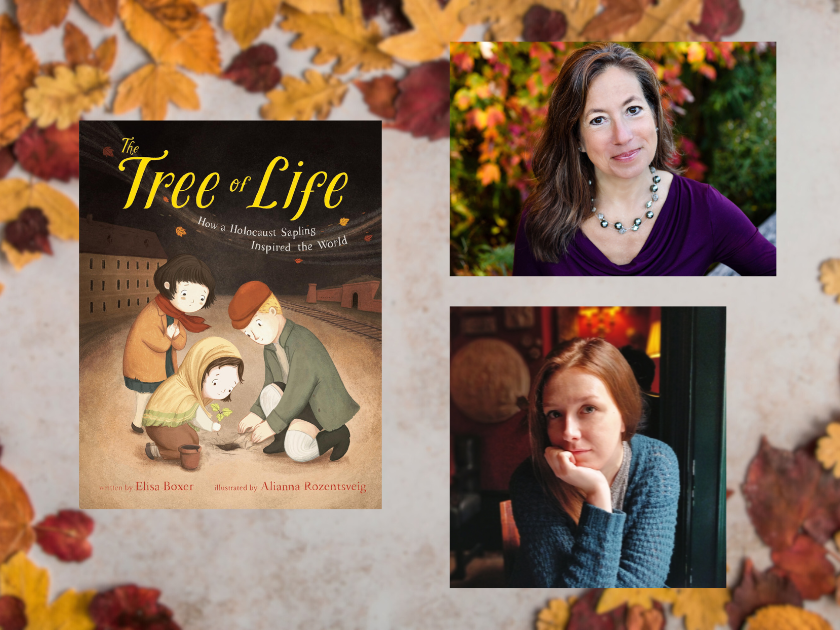

The Tree of Life: How a Holocaust Sapling Inspired the World by Elisa Boxer and illustrated by Alianna Rozentsveig has been honored with a 2025 Sydney Taylor Silver Medal in the Picture Book category. Emily Schneider spoke with the author and illustrator team about their approach to Holocaust education for children and their process for creating this gorgeous book. This interview is part of the Sydney Taylor Blog Award Tour. Find the full STBA blog tour schedule here.

Emily Schneider: First, I’d like to congratulate both of you on your recent award, and on your dedication to communicating difficult truths to children in Tree of Life. Authors and artists choose to frame the Holocaust as a subject in different ways for a young audience, but there is always a common challenge. How do you tell the truth about an unfathomable tragedy while, to some degree, protecting the young reader emotionally? Elisa, how did you approach that problem when writing the book?

Elisa Boxer: Emily, thank you so much. What a beautiful way to put that, the dedication to communicating difficult truths to children. It’s a challenging and delicate balance, to be sure. For me, introducing details about the horrors of the Holocaust in an age-appropriate way, that respects a reader’s capacity for holding the truth, creates the foundation for highlighting stories of resistance, resilience, and hope. That’s always my goal heading into a book, and throughout the writing process. For me, it’s less about protecting children’s emotions, and more about crafting the details in a highly specific and sacred way that honors the subjects, as well as the children reading about them. And always leading with sensitivity. With every book, my aim is to find that tender spot where respect for the story meets respect for the reader.

ES: Alianna, an artist confronts the same issue. Images are as powerful as words. Your pictures of frightened children and desperate caretakers provoke strong emotions. You also include images of Nazi brutality. What influenced your illustration style for this book?

Alianna Rozentsveig: I wanted to be honest, but sensitive, telling the truth and allowing readers to connect emotionally, without overwhelming them. Making sure to balance the darker scenes with moments of hope, happiness, and life, as the story is ultimately about finding hope in the darkest times.

It was actually Elisa that inspired me: “The children were the future of the Jewish people. And the Nazis wanted a future without Jewish people.” It felt as if a child was explaining the Holocaust to me, and I wanted that perspective in the illustrations — always imagining how it would look through the eyes of the children. So I focused on how they would cling to imagination and comfort, showing their innocence and resilience — like caring for the sapling by dressing it in a scarf, holding onto its leaves for comfort, or protecting it from the elements.

ES: One particularly striking example, for me, is the scene of soldiers with their hands held in the Nazi salute. You juxtapose dark red flags with swastikas against a background of grey, and other mixed colors. And you include Hitler himself, not just a mass of generic evil. Was that a difficult or a natural decision for you?

AR: This spread was the one that came most naturally to me, I drew it instinctively, with less overthinking, and it became my favorite. I was always a realistic illustrator. I can’t depict the war without including Nazis, Hitler, or swastikas — they were an undeniable reality. I also believe that hiding something, say Hitler’s face, only fuels fear. In the end, it’s not the face or the salute that are inherently terrifying, but the ideas and actions behind them, and that’s where we tried to be especially careful, and why the main focus in this spread is not the Nazis, but the children and the tree.

EB: I hope it’s ok that I’m chiming in here! When I first saw that page, it took my breath away. The fact that Alianna included Hitler and the Nazis saluting him, with the darkness spilling over to a picture of the children keeping the tree alive… that spread speaks to a deeper place in the soul than my words alone could ever touch.

ES: Elisa, you begin the story with understatement. The children are “scared and separated from their families.” They are uplifted when their courageous teacher helps them to plant a tree, as part of a lesson about the festival of Tu B’Shevat. Then, as their lives worsen, you phrase that process cautiously: “Over time, fewer and fewer children were left to care for the tree.” Alianna’s picture of cattle cars leaving the camp visualizes that fact. I’m interested in how you wrote that sentence, and the following ones that allude to the children’s disappearance.

EB: Such a difficult and delicate balance, as we were discussing earlier. The last thing I ever want to do is minimize the truth, but I have a responsibility to present that truth in a way that honors it without creating trauma. This is where I start with my logical brain and come up with words. But then instinct takes over and I feel into the phrases to deliver the message. That’s what happened with the sentence you mentioned, “Over time, fewer and fewer children were left to care for the tree.” My brain knew it needed to find the words, and that’s where the process began. But ultimately my instinct — and probably my heart too — found that phrasing to convey the message that the children were taken away.

ES: You’ve explained that process really clearly, the way that your intellect and emotions combined in writing the story. Perhaps your choice of the word “miracle,” to characterize the tree’s survival, was a result of that same process. You call its seeds “descendants.” They were eventually planted throughout the world. I noted that, when you reported the survival of the children’s teacher in Terezin, Irma Lauscher, you don’t claim it as a “miracle.” I was impressed with the unstated distinction you made. Books which attribute survival of the Holocaust as miraculous always concern me.

EB: Thank you for recognizing that. I think when Holocaust survival is solely deemed miraculous, it leaves out hard-fought resistance, ingenuity, and a fierce will born out of our instinct to survive in the most treacherous of circumstances. Plus, I believe that we as a people were always meant to come back from the brink of this attempted annihilation. The fact that this tree was planted in secret; that its seeds were already growing and thriving all around the world before the tree itself died; that the tree was essentially reborn hundreds of times over, and continues to grow all over the world to this day, honoring the memory of the children who nurtured a future they wouldn’t get to be a part of and symbolizing our strength as a people— that to me feels miraculous.

ES: Alianna, your pictures of the tree itself chronicle change. At the end of the war, it has some leaves. Later, it appears as much taller and stronger, surrounded by visitors to the Terezin memorial site. But, as the years pass, it dies, and you show it denuded of leaves. Can you tell us how you planned this sequence of pictures, and one of the tree’s revivals at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City?

AR: Since the book centers on a tree and begins on Tu B’Shevat, it felt natural to tell the story through nature, showing how it persists even in the most unnatural, horrific place. It all started with the visual connection between golden Maple leaves in autumn and the yellow star badges. That parallel led me to weave a deliberate seasonal cycle throughout the illustrations: he children receive the sapling in spring, plant it in summer, and the atmosphere reflects their hope. As hardships deepen, the setting shifts to colder seasons — winds rage, and the tree loses its leaves. Then, the cycle renews — liberation in spring, the tree’s death in fall, and its rebirth decades later, with its descendant in sunny New York and the wind ready to carry its seeds to new places. I felt that it mirrored the story of our people, and I was struck by how seamlessly this rhythm propelled the story forward and added to the emotional arc throughout.

ES: Obviously, no single book represents Holocaust literature for children. But would you each like to comment on how, in a world with fewer survivors left, authors and illustrators may respond to that loss?

AR: You know, when illustrating this book, I found myself deeply inspired by the many artist-prisoners of Terezin, most of whom are no longer alive. Despite unimaginable hardships they managed to use their craft to document daily life in the ghetto. Their art outlived them, becoming a vital record — and at times, my only visual reference when creating this very book. It’s why I dedicated the book to them. So, I like to think of this as a joint effort; survivors were never meant to carry the entire burden of commemorating and educating about the Holocaust. It was always our shared responsibility, and now, it’s more important than ever. Looking back on the past year or so, it’s obvious how even a vast, well-documented event like the Holocaust can be distorted and reshaped into countless narratives that push its survivors and victims to the sidelines. Ensuring their stories are uncovered, heard, and faithfully retold is crucial.

EB: Many of the Holocaust survivors I’ve interviewed over the years say they never spoke a word about their experiences, not even to their families, until they began to face their own mortality. In their old age, many of them realized that if they didn’t share their stories, however painful, those stories would be lost forever. Given this, especially at a time with skyrocketing statistics of Holocaust denial, I personally feel driven to shine a light on these stories of survival. And one thing that every single survivor I’ve interviewed has in common, is that they never lost hope. They all say this. This is their overwhelming message, to never lose hope. As children’s literature creators, I think so many of us want to help children feel seen and heard in a world that often shushes them. We want to help give them the strength to be who they are. Although nothing should be directly compared to the Holocaust, I believe that sharing these true stories of people who never lost hope, even in the most unfathomable of circumstances and shining a light on true stories of resistance and resilience and courage can serve as a beacon and a model of inner strength for all children, regardless of religion.

ES: I’d like to thank both of you for sharing your thoughts, and for offering readers an engaging and thoughtful picture book.

EB: Emily, this was such a meaningful discussion, thank you so much for having us.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.