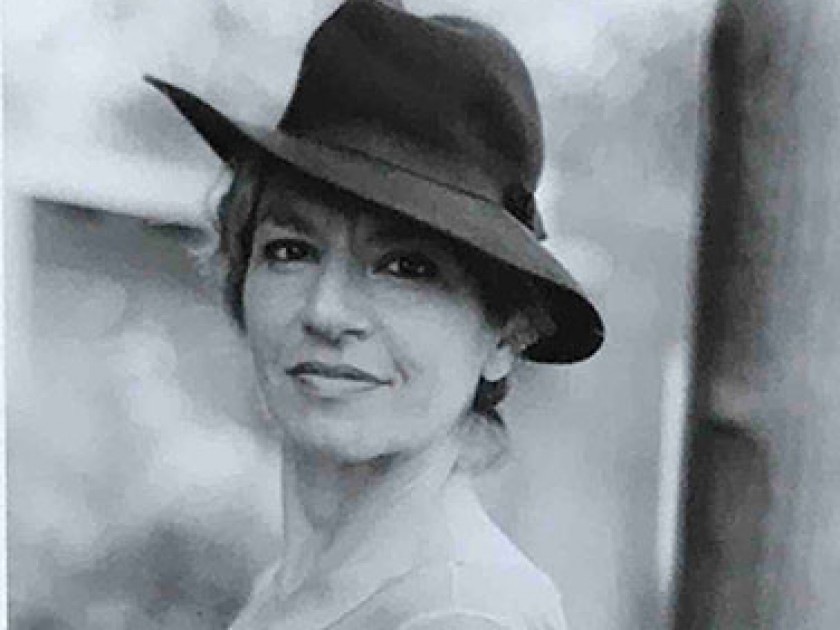

Courtesy of the author

Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, a collection of stories by Bette Howland — a writer who faded out of the public eye after her popularity in the 1970s — has recently been published by A Public Space. In the following interview Brigid Hughes, founder and editor of A Public Space, talks with Howland’s son, Jacob. They discuss Bette Howland’s writing and reading habits, her close friendship with Saul Bellow, and ultimately her perspective on the world and how this shaped her work.

This project of bringing your mother’s work back into print began with the discovery of her book, W‑3 in a used bookstore. We struggled to find any information about her life or work and then just as we were about to give up, we came across a mention of her son Jacob, and emailed you. You wrote back and mentioned finding unpublished manuscripts and a trove of postcards and letters from Saul Bellow. What did you think when you found that trove?

I always knew Bette must have kept their correspondence. Last summer, my brother Frank found another trove in a box she’d left at his house. My first thoughts were, ‘this is fascinating stuff.’ Bellow was always at the top of his game, even in dashing off a postcard.

You quoted from one of his letters in one of the first emails you sent us: “One should cook and eat one’s misery. Chain it like a dog. Harness it like Niagara Falls to generate light and supply voltage for electric chairs.” It was a model for writing she embraced. You’ve written that “she wrote herself out of the grave.” How so?

Bellow wrote those words a few months before Bette’s suicide attempt. She must have recalled them while confined in the psychiatric ward at Billings Hospital, an experience that turned into her first book, W‑3. Writing saved her from being devoured by wild beasts or drowned in a flood of despair. One might say that’s what writing is for.

We published a portfolio of her letters in A Public Space, and she writes frequently to Bellow about her struggles with her work: “A doctor once told me my semi-paralysis was nicknamed, in the profession, ‘perfectionist’s disease.’ ‘I’m not a perfectionist!’ I said. ‘That’s my work!’… You see what I’m getting at. We have to demand this of ourselves in our work. But you can’t demand it in life. We will make mistakes, + it will cost.” How did the demands she made of herself with her writing manifest in life? Why was she so hard on herself?

Bette didn’t suffer fools, and she expressed her opinions frankly and fiercely. She was hard on everybody, not just herself, yet she often regretted her sharp words. She knew she was good, that what she wrote really mattered in American literature. But she also knew that her sons paid for the time and space she claimed for herself, and did so dearly — by which I mean both heavily (as children) and, ultimately, with affection and gratitude for her gifts. Bellow’s accomplishments were the standard by which she measured her writing, and that helps to explain why she was so tough on herself. If you’re going to try to free solo El Capitan, you’d damn well better be a perfectionist.

In one of her letters to Bellow, she writes, “Feeling alone (more so than usual) + in truth a little scared. (It takes a lot of courage to be anyone, anybody; it doesn’t matter who.” What does that mean to you? How do you think about her life and about her work, in terms of that word, courage?

John Stuart Mill said that most people do not “choose what is customary, in preference to what suits their own inclination. It does not occur to them to have any inclination, except for what is customary.” Bette chose to be precisely and exactly herself. And that takes courage in any age. But she was also a single, divorced woman working part-time jobs to support two children. In the 1960s, we lived in dilapidated buildings in dangerous Chicago neighborhoods. It took courage to pursue her dream of a literary career in the face of poverty, loneliness, and the strong disapproval of her working-class parents, who probably never forgave her for dropping out of law school at the University of Chicago. Writers take enormous risks — psychological, financial, social — against long odds. Anyone who sticks with it needs courage.

‘Feeling alone (more so than usual) + in truth a little scared. (It takes a lot of courage to be anyone, anybody; it doesn’t matter who.’

How was she in her daily routine?

Bellow astutely wrote to her that she was “something between a homemaker and a holy anchorite. When you set up your bed, your shop, your shelves of books, you tend to lose all sense of time.” Bette wrote every day, religiously. In the morning, hours of nonstop rat-a-tat-tat on the typewriter at one hundred words per minute. Then she’d fill the typed pages with indecipherable pencil shorthand. In the afternoons, she loved to cook. She made her own yoghurt — a staple in our home — and baked hot loaves daily. Her beet borscht was to die for (secret ingredient: lemon juice). She practiced and taught yoga, and took long walks every day. Even in the last years of her life, four or five miles was nothing for her.

You’ve said that her two favorite words were ardor and vocation. What did they mean to her?

She was passionately drawn toward discovering the truth and meaning of her life, which, in literature, becomes somehow more universally true and meaningful than it would otherwise. That’s the ardor part. Vocation comes from the Latin vocare, to call. Bellow captures her sense of being called in his “anchorite” comment. She was devoted in a quasi-religious way to finding words for the grime and grace of everyday existence.

She wrote to Bellow: “Other people don’t have my habits — true; who would wish my habits on anybody.” And in an aside: “It bugs me when they don’t have habits of their own.” I love that wry humor, which is so much a part of everything she wrote. What are the qualities in her writing that most capture her for you?

Bette read very widely — Homer, Durkheim, Freud, you name it — and I’ve recently come to appreciate how much the intellectual tradition resonates in her work. Deeply funny passages complement her tragic sense that the puzzles of our lives simply can’t be completed — you push one piece into place and another pops out. But I’m most struck by her astonishing powers of observation, her ability to size people up in soul and body and capture their distinguishing characteristics in a few deft strokes.

So much of her writing is set in Chicago, though she left the city in 1975 and chose to live, for the most part, in very different environments, such as an island in Maine. She told an interviewer, “This town is one of the great loves of my life. When I lived there, I didn’t know it. Now that I’m gone, I do.” Why do you think she needed that distance?

Inner city Chicago is a cold, hard place. Bette writes about this in stories like “Blue in Chicago” and “Public Facilities.” I think it ground her down, and she sought refuge in more isolated regions like Albuquerque, a farm in central Pennsylvania, a Quonset hut near the shore of Lake Michigan, and an Indiana farmhouse.

What books did she read to you when you were little?

She read us Tolstoy’s short stories. When I was around six and my brother was seven, she read us “How Much Land Does a Man Need?,” but we had to go to bed before the end. Frank got up and read the rest to me the next morning. She introduced us to Isaac Babel and I. B. Singer. She gave me a copy of Richard Wright’s Black Boy when I was around ten years old. This book had an enormous impact on my life. His attempt to “wring a meaning from meaningless suffering” described what I saw my mother doing every day. She wanted us to experience the full range of culture. She would take us to concerts in the park, the Art Institute, and plays at the University of Chicago. We used to go to the Clark Theater and watch films. (Bette had a big poster of Clint Eastwood, in a poncho and with a cigarillo dangling from his mouth.)

Did you ever talk with her about her writing?

Bette was always hesitant to share work in progress. I learned at about age fifteen not to be too critical of her writing. Looking back, I can’t imagine what I might have objected to!

How has your understanding of her work changed, with the distance of years?

I didn’t read her work until W‑3 was published. For some reason, it was Blue in Chicago that made the biggest impression on me, maybe because I was nineteen by then and reasonably capable of understanding just how good her work really is. But as you know, I think her novella Calm Sea, first published in TriQuarterly (1999), is her masterwork. Rereading that work recently, I realized that my mother’s writing isn’t just very, very good. It’s great. It deserves to be taught in universities and studied by professors of literature. I think she’d get a good laugh at what literary critics in the academy might write about her.

For some reason, it was Blue in Chicago that made the biggest impression on me, maybe because I was nineteen by then and reasonably capable of understanding just how good her work really is.

What do you remember of her relationship with Bellow? What isn’t in the letters that is important to understanding their relationship?

Bellow used to come over to Bette’s apartment and we’d play with Adam and Daniel while they read their manuscripts to one another. Frank reminded me of the time Bellow read from a draft of Mr. Sammler’s Planet and she criticized it and he left in a huff. But Bette was always proud of helping him to improve that book — one of my favorite Bellow novels.

Apart from Saul Bellow, who were some of the writers who meant the most to her? In one of her letters, she mentions working on a thesis about Henry James. You read the Iliad to her at the end of her life, when she was suffering from dementia, which she loved.

She felt a deep connection to Chicago writers like Dreiser, Richard Wright, and James T. Farrell. She loved An American Tragedy, Sister Carrie, Native Son, Black Boy, Studs Lonigan, James Fenimore Cooper, Huckleberry Finn, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, The Education of Henry Adams, Lord Jim, Stephen Crane, Faulkner, Arnow’s The Dollmaker, Henry James (especially Portrait of a Lady), Henry Roth’s Call it Sleep. Roth and his wife were good friends. Late in life she began to study the Hebrew Scriptures, and she published in this area as well. In terms of literary criticism, she highly valued Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis and D.H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature.

Could you talk about her novella “Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage”? As with much of her writing, it tells a story from her own life and in this case, a relationship with a philosophy professor, who was also your mentor.

Right. The fictional protagonist of Victor Lazarus resembles my first teacher of philosophy and dear friend, who died at forty-seven. “Calm Sea” recounts the last days of the narrator’s former lover, Victor Lazarus, a brilliant, alcoholic philosopher and scholar of Torah and Logos, hounded even on his deathbed by his ex-wife, a frenzied orphan of the Holocaust. Victor is a poisoned Socrates or a victim of Jewish fate, his ex-wife a Fury or a dybbuk, his story a Greek tragedy or a Hasidic tale. The novella leaves us wondering, to borrow Victor’s words, whether “the sheer consolations of Myth” really do, in the end, “exceed the mournful contingencies of the True.”

Brigid Hughes is the founding editor of A Public Space. Previously, she worked at the Paris Review with George Plimpton, succeeding him as editor in 2003. She teaches at Columbia University, and at A Public Space has collaborated with such cultural organizations as BAM, the Guggenheim Museum, and PEN on literary programming. A graduate of Northwestern University, she lives in New York City.

Jacob Howland is McFarlin Professor of Philosophy at the University of Tulsa. His essays have appeared in The New Criterion, Commentary, the Jewish Review of Books, and the Claremont Review of Books, among other publications. His latest book is Glaucon’s Fate: History, Myth, and Character in Plato’s Republic (Paul Dry Books, 2018).