If I think about time too hard, I find myself going in circles. The ways that time works on relationships — how the past and the present can be in ongoing conversation. The accumulation of memory and how that shapes our understanding of each other, and then, too, how the lack of time also influences the dynamic between people — the power of a brief encounter. A great thing about fiction is its ability to explore this motif of time and relationships without having to be conclusive, without having to gather evidence solely in order to reach a point. Fiction allows you to go in circles but still end up somewhere new.

My novel, The Summer Demands, centers on an ambiguous, intense bond formed over a summer between the thirty-nine-year old narrator, Emily, and a young woman named Stella. Emily also has a husband, David, and they’ve been married for years —they’ve continually made the choice to go through life together. When trying to evoke the complexity of these relationships in my own work, I kept going back to writers who have handled it so expertly. Some of them delve into relationships that are sustained over time —motherhood and daughterhood in Chantal Akerman’s My Mother Laughs, and marriage in James Salter’s Light Years and Natalia Ginzburg’s “He and I.” Others focus on relationships that are brief but whose effects echo long after, such as the coming-of-age romance in André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name. While Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home concerns both the long haul and the fleeting but decisive moment.

I think there’s a common Jewish thread in the way these works approach this territory. Aspects of the diaspora — particularly questions of exile and belonging — play a role in each one. Those questions surely tint the interactions of characters and the mindsets of narrators here.

Swimming Home by Deborah Levy is a short, stunning novel whose compressed form carries so much life. An English family is on vacation in the south of France: celebrated poet Joe Jacobs, a Kindertransport refugee from Poland whose parents were killed in the Holocaust, his wife Isabel, a war correspondent, and their fourteen-year-old daughter Nina.

At their rented villa, they encounter the young twentysomething Kitty Finch, with her long copper hair and green painted nails, who first appears swimming naked in their pool. She’s a mercurial presence who sets in motion a story that plays off the elusive ideas of home and safety against trespassing and desire — desire for, well, just about everything. It’s a novel of wit and beauty laced with fragility and dread, and it’s almost musical in its purposeful repetition and rhythm.

What seems on the surface like a story of upper-middle class marriage and fairly typical infidelity (successful older man, aspiring younger woman) becomes much more than that, especially and ultimately in the ways it looks at daughterhood — what we know, what we think we know, and what we’ll never know about our parents and how that knowledge (or lack thereof) reverberates in our selves.

Light Years by James Salter is a complicated book, like its author. And loving it is complicated, too. In a 2013 profile of Salter in the New Yorker, Nick Paumgarten notes that Salter, who was born James Horowitz in 1925 and legally changed his name, has “said that he didn’t want to be thought of as another Jewish writer from New York; there were enough of those.” There’s no Philip Roth-style New York by way of New Jersey humor here, only a kind of cool, Continental sophistication. In this novel, Viri and Nedra enjoy a carefully depicted home life with their two daughters in a town along the Hudson River. Over decades, affairs and betrayals ensue.

I could read this one again and again for the refined beauty of Salter’s imagery. For the mood, atmosphere, and sheer sensory pleasure of being transported to the world that he creates. In that New Yorker piece, Paumgarten suggests that to appreciate Light Years: “Maybe you have to have, in addition to a taste or a tolerance for the prose, a certain sentimental cast of mind — an attraction to domestic contentment, and a panged sense of its passing quickly, into nothing.” Check and check! I’ve heard the criticism that this book doesn’t capture the messiness of marriage and divorce and, more generally, that Salter writes as if women over forty-five should just call it quits. I don’t disagree with that assessment, but I’d argue that nobody over forty-five — regardless of gender — ends up all that well in Salter’s work and that’s part of the point. A theme of lost youth runs through so much of his writing and this romanticism isn’t easy nostalgia; it’s the struggle of living in and with the passage of time.

Where do you start with the extraordinary Natalia Ginzburg? She was born in 1916, to a large family (Jewish father and Catholic mother) at the center of cultural and academic life in Turin, Italy. Her first husband, Leone Ginzburg, a professor of Russian literature and anti-fascist Resistance fighter, died in prison in 1944. Ginzburg later married Gabriele Baldini, a professor of English literature, whom she wrote about in this short piece, “He and I” from the essay collection, The Little Virtues.

It’s ostensibly a catalog of their differences: he’s a good singer, she sings out of tune, he’s always hot, she’s always cold, he loves to travel, she’s a homebody, he respects established authority, she fears it, and so on. Eventually, she flashes to one of their early meetings: “I don’t even remember what we talked about on that evening walking along the Via Nazionale; nothing important, I suppose, and the idea that we would become husband and wife was light years away from me.” They lose sight of each other, as Ginzburg puts it, before reconnecting years later. “I sometimes ask myself if it was us, these two people, almost twenty years ago on the Via Nazionale… who chatted a little bit about everything perhaps and about nothing; two friends talking, two young intellectuals out for a walk; so young, so educated, so uninvolved, so ready to judge one another with kind impartiality; so ready to say goodbye to one another for ever, as the sun set, at the corner of the street.”

The reader may or may not know what Ginzburg endured over those intervening twenty years — she doesn’t directly address it in this piece. What she does do here, so economically, is get at the shocking arbitrariness of marriage and the deep mystery of it, particularly how a long-term partnership might play out over the course of time. How it can reward you in ways you didn’t even know to expect.

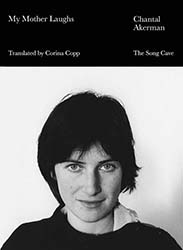

The avant-garde works of Brussels-born filmmaker Chantal Akerman are a study in how people move within time and space. And a sense of displacement is never too far away. The same goes for My Mother Laughs, a memoir in which Akerman chronicles the failing health of her mother, Natalia “Nelly” Akerman, her own mental health, her work, and her love life. First published in 2013 in French, an American edition translated by Corina Copp came out in 2019.

Akerman’s mother was an Auschwitz survivor and Akerman was “born into trauma,” as she once said in an interview. Her extreme closeness to her mother defined a great deal of her creative output — from her early work, News From Home (1977), in which Akerman reads letters from her mother over street and subway shots of lower Manhattan, to her final film, No Home Movie, a documentary portrait of Nelly in her last years, featuring conversations between mother and daughter. It appeared in 2015, the same year Ackerman committed suicide.

My Mother Laughs is often painful to read, but it’s also shot through with moments of light and melancholy humor. Akerman’s language is precise while her subject matter is discursive, wandering. Just as there’s sometimes disjunction or delay between sound and image in her films, there’s a shifting of tenses right from the beginning of this book: “I wrote all of this and now I no longer like what I’ve written. It was before… before I understand that I might have misunderstood everything.” Which leaves you wondering about beginnings and endings and all the time that moves in between.

Among these recommended books, Call Me By Your Name by André Aciman is probably the most well-known, or at least the most widely-read. Does it even need an intro? Okay, a short one: It’s a summer romance between seventeen-year-old Elio and Oliver, the twenty-four-year-old house guest his academic parents host over the course of six weeks in the Italian countryside.

There’s a lot of lounging and swimming, eating delicious meals prepared by a cook, and being erudite (Elio makes a reference to writer, painter, and activist Carlo Levi, who led an anti-fascist movement with Natalia Ginzburg’s first husband, Leone — it’s a world not so far removed.) Elio first lays eyes on Oliver, in his “billowy blue shirt, wide-open collar, sunglasses, straw hat, skin everywhere,” and is struck by his seemingly unflappable confidence. It’s no small thing that Oliver’s wide-open collar reveals a gold Star of David necklace, and makes Elio keenly aware of his own self-consciousness. As Elio elaborates: “We wore our Judaism as people do almost everywhere in the world: under the shirt, not hidden, but tucked away. ‘Jews of discretion,’ to use my mother’s words.”

Aciman evokes all the intensity, confusion, and frustration of youth — all the wanting. At the same time, this novel is retrospective; it’s Elio’s midlife reflection on this period. Which suggests that coming of age is not simply about growing older, it’s a lot to do with learning how to read people, how to read the world, how to read your past self — it’s not a one-time dropping of the veil, but a continual process that takes place over a lifetime.

Deborah Shapiro was born and raised outside of Boston, Massachusetts. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, Sight Unseen, Tin House, and elsewhere. Her first novel, The Sun in Your Eyes, was selected as an Editors’ Choice by The New York Times Book Review, as well as one of the season’s best reads by Harper’s Bazaar, The Wall Street Journal Magazine, Chicago Tribune, and Vulture, among other publications. She lives with her husband and son in Chicago.