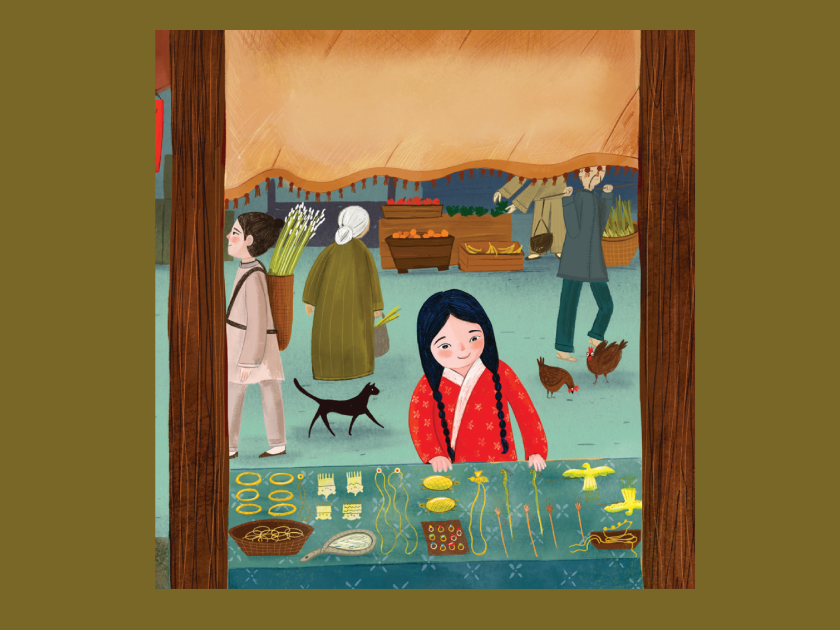

Illustration by Renia Metallinou from Zhen Yu and the Snake, cropped, courtesy of the author

As a mother, I was, as one would expect, extraordinarily contemplative when naming my children. Picture book authors, and fiction writers generally, do the same for our characters. By giving them names, we give them a past, a present, and a future. They link us to our ancestors; they afford us agency in the present; and they allow us to be remembered as far more than someone else’s daughter or wife. One of the many things I love about writing picture books is that I have permission to do all of these. I can go back and write the stories of the girls in biblical texts who weren’t given stories of their own. I can give them names, too, as part of a growing trend, in picture books, of reinterpreting these texts from a feminist perspective — and, in a sense, creating modern midrash.

My first experiment with this was many years ago, when I read the story of Jepthah’s daughter in my university class, Gender and Jewish Women in Historical Perspective with Dr. Judith Baskin. I wrote this unnamed girl a poem. The story stayed with me, the rhythm of the daughter’s timbrel, the echo of her lamentations. It still does. I can picture her clearly. While it’s often referred to as the story of Jepthah’s daughter, this is a misnomer. She was merely a narrative device placed for readers to extrapolate some lesson, perhaps the folly of her father or the proscription on making vows or to reiterate the status of women. As I learned in Gender and Jewish Women in Historical Perspective so many years ago, women in Judaism often fared better than their non-Jewish counterparts, but Jepthah’s daughter most certainly did not fall into this generalization. After all, she’s allowed to be sacrificed. She’s no Isaac, and God doesn’t intervene. Furthermore, it’s not even the loss of her own life for which we hear her lament, but rather her wasted virginity, a commentary on the value of a young woman whose purpose is unfulfilled never having had the opportunity to be a wife or mother.

Despite many years of Jewish education prior to this class, I had never heard of Jepthah and certainly not of his daughter. At that moment, I suddenly realized that there were numerous other nameless girls and women that our texts only hinted at, whose names and stories I would never know and whom yet I couldn’t stop thinking about.

While Jepthah’s daughter will never come of age, Jewish feminist picture books have. Picture books tackle complex emotions, ideas, and events and provide commentary in a manner accessible for young children; they educate and enlighten without being didactic. And they can give names and stories to those girls formerly denied them in our ancient texts.

In my new book, Zhen Yu and the Snake (illustrated by Renia Metallinou, Kar-Ben, 2023), I retell the story of Rabbi Akiva’s daughter and the snake, setting the tale in twelfth-century Kaifeng, China. Rabbi Akiva’s daughter and the snake is a small and often overlooked story in the Talmud (Shabbat 156b). Like Jepthah’s daughter, she too is unnamed and is defined only by her role relative to men (daughter and then wife) because she too wasn’t seen as important as an individual. It gave me great satisfaction to be able to name her in my version – Zhen Yu or Precious Jade. I had in mind the song “Eshet Chayil” which details the attributes of the idealized Jewish wife: “A woman of valor who can find? For her price is far above rubies” (Proverbs 31:10 – 31). The little we know of Rabbi Akiva’s daughter, like Zhen Yu, embodied these ideals.

In the Talmud, we learn that a fortune teller warns Rabbi Akiva that his daughter will be bitten by a snake on her wedding day and die. No particular precautions are taken to protect her nor does she show any propensity to defend herself. We are told only that she was worried. Unfortunately, seemingly no one else was. Instead, on her wedding day, she accidentally kills the snake when she places her ornamental hairpin into the wall for safekeeping so that she can give a gift to a beggar. The lesson being “charity will save from death” (Proverbs 10:2).

When drafting Zhen Yu and the Snake, I first imagined another version, where Zhen Yu goes to great lengths to save herself. I initially wrote her as a woman who actively avoids being bitten by a snake, something noticeably absent in the Talmud, and echoing the Yiddish proverb – hope for a miracle, but do not rely on one.

Ultimately, my self-actualized Zhen Yu didn’t make it to the page. While from a contemporary lens, the Talmud’s version is unsettling, I let aspects of it stand and Zhen Yu’s role remains traditional in my retelling. But by giving her a name she gains more power. Readers are given a glimpse into a fictionalized version of the Jewish community in Kaifeng, believed to have been established during the Song dynasty (somewhere between the ninth and twelfth centuries) by Persian Silk Road Traders. It is here where a chance meeting with a fortune teller occurs as a result of Zhen Yu wandering off in the market. While this is a much more subtle reimagining than the somewhat brash Zhen Yu I first pictured, I don’t allow her to merely passively worry. The warning about the snake is withheld from Zhen Yu and the decision not to act is placed solely on her father instead.

I suddenly realized that there were numerous other nameless girls and women that our texts only hinted at, whose names and stories I would never know and whom yet I couldn’t stop thinking about.

The approach I took in Zhen Yu is quite different from the approach I took in my picture book Counting of Naamah: A Mathematical Tale on Noah’s Ark (illustrated by Mary Reaves Uhles, Intergalactic Afikoman, 2023). In this retelling I take great liberties and bring the past into the present. Warning, this is an interpretation that one needs a sense of humor to appreciate; this is a Naamah who develops the prototype for the first life preserver.

I thoroughly deconstruct the flood story as we know it and allow Naamah to be smart, creative, and industrious. The name Naamah means pleasant, and suggests the role she and other women were expected to have. I invite readers to set aside their preconceived notions and accept that, “though her name meant pleasant (and she was very nice), Naamah was known best for being clever.”

Unlike Jepthah’s daughter and Rabbi Akiva’s daughter, however, Naamah is known in the text for being a wife. Her name, however, is rendered to near obscurity , as she isn’t explicitly named in the flood story in the Torah. Noah is instructed to bring “your sons, and your wife and your sons’ wives with you.” We are told the three sons names, but it is only through midrash that we learn Naamah’s.

Naamah is not specifically mentioned as being merited as worthy to be saved from the flood as Noah is, rather she is just named as Tubal-cain’s sister. Interestingly, she is not only Tubal-cain’s sister, but also the half-sister of Jabal and Jubal though that isn’t explicitly stated. Given the extraordinary talents and contributions to civilization of all three of her brothers as the inventors of music, tools, and animal husbandry (as per traditional midrash), it was impossible for me not to imagine Naamah as being at least equally capable of inventing and creating as her brothers, had she been given the chance.

While Counting on Naamah is a wild ride where outrageous antics ensue, it’s also a modern commentary on the blank spaces between the text, where a woman, virtually unnamed but pleasant enough to be saved, lived her life.

Quite similarly, in Queen Vashti’s Comfy Pants by Leah Berkowitz (illustrated by Ruth Bennett, Apples & Honey Press), Berkowitz takes readers on a fun, frolicking adventure in the Persian King Ahasuerus’s court where the situation for women was anything but. All we really know of Vashti in Megillat Esther is that she threw a lavish ball for the women and then refused to come to the king when he beckoned. For this refusal a declaration is made, “If it please Your Majesty, let a royal edict be issued by you, and let it be written into the laws of Persia and Media, so that it cannot be abrogated, that Vashti shall never enter the presence of King Ahasuerus.” Vashti loses her title and some say her life.

In her picture book, Berkowitz is able to give Queen Vashti a tremendous amount of agency as Vashti leads the other women out of court to a life where they are not bound by court rules or dress codes. This too is midrash. Queen Vashti’s Comfy Pants allows her another change, rewriting her with modern sensibilities and allowing her to stand on her own as a feminist icon. Moreover she can now wear comfy pants with wild prints. And all this is marvelously accomplished in rhyme and colorful, engaging illustrations.

In the same vein, Jane Yolen in Miriam at the River (illustrated by Khoa Le, Kar-Ben Publishing, 2020), refocuses the narrative to feature Miriam. Miriam, unlike many other women, is already presented as a woman of action and one that has a voice. We’re told in the Torah that like her brothers, she too is a prophet, one of seven women out of the fifty-five prophets explicitly named in the text. It might even be argued that she has more of a role than her brother Aaron. Even as a prophetess, though, God reminds her that she is not like Moses. “When prophet so of God rise among you, I make Myself known to them in a vision, I speak with them in a dream. Not so with My servant Moses; he is trusted throughout My household. With him I speak mouth to mouth, plainly and not in riddles…” (Numbers 12:6 – 8).

Yolen, however, in her book also allows God to speak to Miriam. “But I ask God anyway. Like a soft breeze, that comforts in the middle of an Egyptian summer, God whispers in my ear…” God’s response to Miriam, in Miriam at the River, allows her to feel at ease with the decision to place Moses in the Nile.

Yolen’s story focuses on one small part of Miriam’s early life and expands the reader’s understanding of that key moment. Had she not placed Moses in the river, perhaps none of the story would unfold the way that it did. But what did it feel like to place him there? Yolen takes what we know of Miriam from midrash and allows us to understand her not only in the words of Talmudic sages, but in her own voice. She gives Miriam an inner dialogue that isn’t present in the Torah. We are able to stand with her at the river and experience it through her eyes. In Miriam, Yolen found the perfect woman to add intent to her actions.

All of these girls and women could have been inventors, rulers, poets, or warriors had they been born at another time. Had the women in our texts been given the opportunity to write their own stories and to reach their potential, those are stories that I most certainly would have loved to read. But they didn’t, so the task of reinventing their lives and interpreting the blank spaces is left to us.

Illustration by Renia Metallinou, cropped, courtesy of the author

Erica Lyons is chair of the Hong Kong Jewish Historical Society and is the Hong Kong Delegate to World Jewish Congress. She’s also the founder and manager of PJ Library Hong Kong. She lives in Hong Kong.