Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

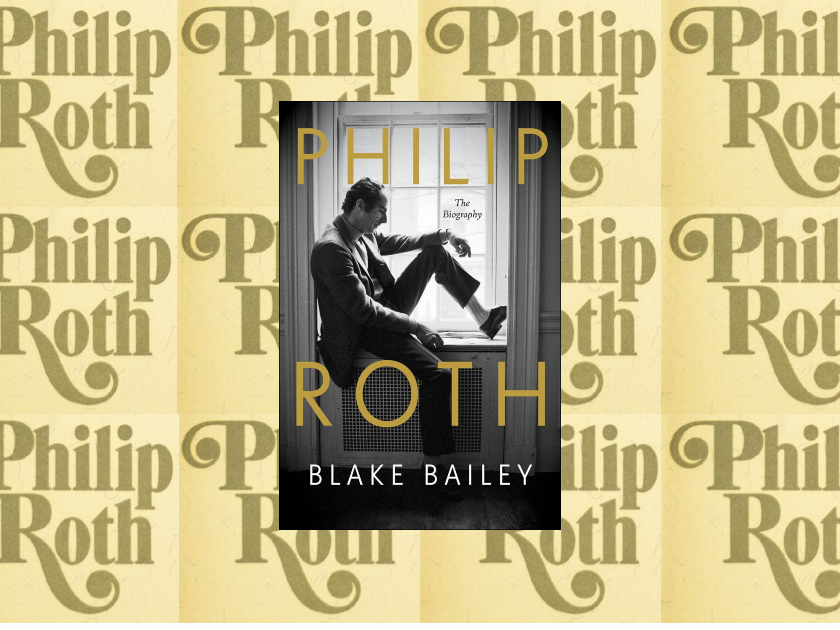

Distinguished literary biographer Blake Bailey observes, “If you tell the whole truth about a person their humanity comes through.” Author of A Tragic History: The Life and Work of Richard Yates (2003) and Cheever: A Life (2009), among other titles, Bailey’s latest work is the monumental Philip Roth: The Biography. Donald Weber spoke to Bailey on the challenges in taking on Roth as a subject, his autobiographical playfulness, and his critics.

Donald Weber: Taking on the figure of Roth would seem, at first, like a radical departure from your previous biographies of John Cheever or Richard Yates. When Roth interviewed you about becoming his prospective biographer, he asked “Why ‘a gentile from Oklahoma should write [his] biography?’” What drew you to Philip Roth as a subject for biography?

Blake Bailey: My answer to Philip’s question about my Okie gentileness was, I think, roughly the answer he wanted to hear: “I’m not a bisexual alcoholic with an ancient Puritan lineage, but I wrote a biography of John Cheever.” Throughout his career, Philip repeatedly said (in so many words), “I’m not a Jewish American writer. I’m an American writer who happens to be a Jew.” Maybe we should take this with a grain of salt, given the dominance of Jewish themes in his work, but another major theme was the Jewish (or Black, in the case of Coleman Silk) hero’s rejection of his own community so that he can pursue his own interests, be they artistic or otherwise — the “I against the They,” as Philip put it. As a biographical subject, I think Philip actually preferred not being judged primarily as a Jew or by a Jew, which is not to say that he had a problem with Jewishness per se. Philip loved being a Jew and living among Jews on the Upper West Side.

DW: In his Paris Review interview with Hermione Lee, Roth famously explained his literary method: “Making fake biography, fake history, concocting a half-imaginary existence out of the actual drama of my life is my life. There has to be some pleasure in this job, and that’s it. To go around in disguise. To act a character. To pass oneself off as what one is not. To pretend.” As his biographer, how did you navigate between your subject’s fabricating impulse and what he called, perhaps also with a sly wink, “the facts” of his life?

BB: Roth’s collaboration with me was a different exercise from writing fiction. In everyday life, and certainly in his own biography, he prized accuracy above all. Because he’d transmuted so much of the raw material of his life into fiction, he did have a tendency to misremember certain episodes — such as various details relating to his first wife’s tricking him into marriage with false urine that she’d purchased from an obviously pregnant woman in Tompkins Square. The essential story is true, but he’d tried to make fiction out of it so many times — hundreds of times! — that he could no longer distinguish between imagination and fact. When I would show him proof that he’d misremembered something, he was apt to concede the fallibility of his own memory.

DW: Discussing Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, which caused substantial offence among some of his Jewish readers and some critics in 1969, you speak of the novel as a “crucial breakthrough,” in contrast to Irving Howe, who described it in 1972 as “a shriek of excess.” Why did Portnoy cause such a stir at the time, especially among Jewish readers? Revisiting the novel a half-century later, do you think Portnoy continues to offend?

BB: I like to think that Portnoy is enduringly offensive, yes, insofar as it’s one of the filthiest books — perhaps the filthiest great book, period — ever written. As a supposed indictment of Jewish life, not so much. When the Jewish Theological Seminary awarded Roth an honorary degree in 2014, they were essentially proffering a peace pipe — or throwing in the towel. “Roth has won,” the Forward announced two years before; “American Jews today are more the heirs of Portnoy than of his upright community. … We can laugh today because we are no longer compelled to cry.” In short, times have changed. As for why it caused so much outrage in the first place, well, I suggest readers revisit the novel and reach their own conclusions.

DW: Looking back, Roth reflected that Portnoy “takes delight in his own grievances.” You speak of Roth “trying to gain perspective on a grievance that would not leave him in peace, as a writer or as a man.” Why was Roth so afflicted by grievance, and yet so creatively inspired by what drove him crazy?

BB: Quite simply, if Roth weren’t such an obsessive personality, he wouldn’t have been a writer in the first place — or rather, he wouldn’t be one of the greatest writers who ever lived. Let Roth speak for himself: “Over commitment for a writer is the name of the game. There’s no other way to persevere up against the obstacle that writing fiction presents. … The intensity, the intensity — it kills you and it makes you all at once.” Also, consider the relative breeziness and charm of Roth’s first book, Goodbye, Columbus, as opposed to many of the works that followed — that is, after he’d been reviled as a self-hating Jew, sex fiend, misogynist, and so on. Roth had an impious, provoking nature and brought much of this on himself, and he kept on provoking as grievances mounted on both sides: a vicious cycle?

DW: In a key observation you state, “One of Roth’s breakthroughs was a determination to ‘let the repellent in’ — a phrase that would assume the force of a manifesto over the years.” How did Roth transform and translate the “repellent” into art?

BB: For its translation into art, see Portnoy’s Complaint, Sabbath’s Theater, et al. As for its real-life origins: Chekhov had to “squeeze the serf out of [himself] drop by drop,” and likewise Roth was determined to squeeze the Nice Jewish Boy out of himself drop by drop (he never quite succeeded). The Nice Jewish Boy wrote sensitive apprentice fiction in the mode of Capote and Salinger; the Nice Jewish Boy was so eager to be a mensch that he married a woman whose company he’d come to dread. The latter ordeal made him seethe with grievance the rest of his life, and the main outlet for that was his writing.

In the novel Nathan comes to the wrenching conclusion that he has to reject his family for his art — a decision Roth never had to make, since his doting parents supported him no matter what the rabbis said.

DW: In light of Roth’s portrayal of women in his fiction, and the charge of misogyny — an accusation which he detested and strenuously defended himself against — I was struck by how, over the years, he came to rely on female readers to whom he sent drafts of his novels-in-progress: Roslyn Schloss, Veronica Geng, Judith Thurman, Hermione Lee, Claudia P. Roth, Lisa Halliday, among them. Can you speak on this?

BB: That was Philip’s position: all his life he’d had friendships with formidable intellectual women; his lawyers were women, his favorite editors were women, his first agent was a woman, his lifelong mentor from Bucknell, Mildred Martin, was a woman. On the other hand: Philip didn’t have a monogamous bone in his body, and was quite capable of sexually objectifying women and making tasteless jokes about it, many of which he wrote down in his novels. Also, he married a famous actress who resented his adultery and abandonment and wrote a book about it. So it’s messy.

DW: In a recent essay, Nicole Krauss speaks movingly of her friendship with Roth and his advice about appropriating personal experience and history for the purposes of art. Roth exemplifies a writer “plundering from life.” Your work, Philip Roth,reveals again and again Roth “cannibalizing” his own story. As his biographer, how did Roth’s habit of “plundering” shape your own approach to telling his life story?

BB: In just about every case, I knew precisely where fiction and reality diverged — and if I didn’t know, I simply had to ask. For example, Philip took an almost playful (or perverse) pleasure in admitting to me that most of “Philip’s” transgressions in his novel Deception—the English mistress and other illicit affairs — are based on fact. In the case of Portnoy, though, he was always indignant that so many readers had simply accepted the novel as (mostly) a confession. The truth, as I say in my book, is complicated, and I try to spell that out as precisely as possible.

DW: What’s your sense of Roth’s influence on younger writers? Can we speak of a Rothian legacy to the rising generation? (Roth invited Zadie Smith to give the Inaugural Philip Roth Lecture at the Newark Public Library in 2016.)

BB: The main lesson is the one Zadie Smith explains in her Philip Roth Lecture: “I know that I stole Portnoy’s liberties long ago. … He is part of the reason, when I write, that I do not try to create positive Black role models for my Black readers, and more generally have no interest in conjuring ideal humans for my readers to emulate.” It was a point Philip made in various ways throughout his career: Hamlet does not stand for all Danes, Raskolnikov for all Russians or students, Othello for all Moors, nor does Portnoy stand for all Jews, Maureen Tarnopol (in My Life as a Man) for all women, and so on. Let the repellent in; literature is not propaganda.

DW: The opening sections of the biography offer a rich portrait of Roth’s family history, above all the immigrant generation of his father, Herman. Roth celebrated that generation — particularly in The Plot against America—speaking of his father as “very much a man in the middle for most of his life. To negotiate from the middle…became not only his task but the endeavor of his entire generation.” Roth kept in touch with various family members over the years. At the same time, one of Roth’s core themes, as you note, is “The I against the They.” How did this tension, between Herman as father-in-the-historical middle and Roth as son, himself generationally in the middle (between World War II and Vietnam), shape Roth’s literary and political imagination?

BB:In the first novel of the Zuckerman cycle, The Ghost Writer, the hero’s beloved father begs him to disavow a short story based on a family squabble, because gentiles will read it as a story about “Kikes and their love of money.” In the novel Nathan comes to the wrenching conclusion that he has to reject his family for his art — a decision Roth never had to make, since his doting parents supported him no matter what the rabbis said. The young Roth, flowering intellectually — and a little pretentious as flowering young intellectuals will be — went through a bitter phase vis-à-vis “philistines” like his insurance-salesman father, his comme il faut mother, but came to appreciate their decency, work ethic, and total devotion to him.

Donald Weber writes about Jewish American literature and popular culture. He divides his time between Brooklyn and Mohegan Lake, NY.