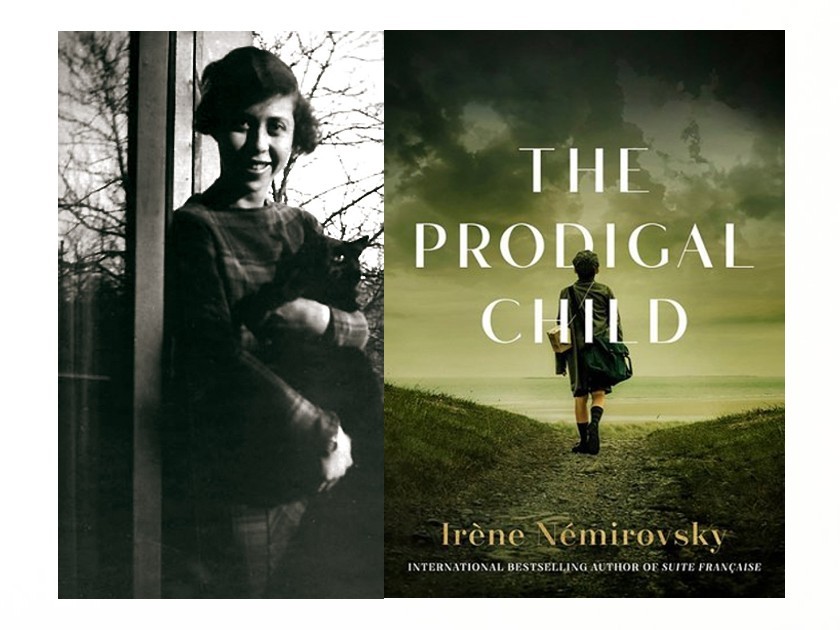

Irène Némirovsky 25 years old, 1928

In 2005, I was fortunate enough to be selected to translate Irène Némirovsky’s masterpiece, Suite Française into English, which was published worldwide in 2006. Following its success, I also translated eleven of her other novels, written between 1929 and 1942 before she was deported and murdered at Auschwitz.

Over the ten years I worked on Némirovsky’s books, I learned a great deal about her life — the history of the times in which she wrote, her perspective on living in Russia as the daughter of a wealthy banker, and then her time in France as a “stateless Jew.” I was also extremely fortunate to have become close to her one surviving daughter, Denise Epstein. I travelled with Denise, serving as her interpreter at interviews and many other events from 2006 until her death in 2013. To many, Némirovsky was a great writer whose life had been tragically cut short, but to Denise, Irène was simply her mother. Denise gave me insight into their life as a family that I could not have come to understand otherwise.

Many biographical elements appear in Némirovsky’s works and The Prodigal Child is no exception. Némirovsky wrote it in 1923, when she was only twenty years old, but it was not published until 1927. While it is clearly an early work that experiments with inserting classical elements into the narrative, it is fascinating to see how she manages to intertwine references to so many different genres.

The story has an allegorical and biblical style, and also works as a type of fable. The symbolism is obvious (and meant to be). The title reminds us of the biblical story of “The Prodigal Son.” The protagonist is named Ismaël Baruch. Ismaël is the French name for Ishmael, the first son of Abraham and his handmaiden Hagar, who were cast out when Sarah gave birth to Isaac; they wandered through the desert and Ishmael is credited with being a prophet — if not the founder — of Islam, while Abraham and Isaac carried on the line of Judaism.

The protagonist’s last name, Baruch, is the Hebrew word for “Blessed,” and most Hebrew prayers begin with “Baruch atah Adonai” (Blessed are you our God).

So the novel begins with a paradox: the protagonist is both blessed and cast out, and this theme continues throughout the work.

At the start of the story, Némirovsky describes the abject poverty of the poor Jews living in a large port town on the Black Sea at the turn of the twentieth century:

[The] family grew larger every year, for children multiplied like insects in the Jewish quarter. They grew up in the streets. They begged, argued, swore at passers-by, rolled around half-naked in the mud, ate vegetable peelings, stole, threw rocks at dogs, fought, filled the street with an ungodly clamor that never ceased. The Baruchs had fourteen of them. As soon as they were old enough, they left for the port, where they did all sorts of odd jobs: they helped the longshoremen and porters, sold watermelons they’d stolen, begged for alms, and prospered like the rats that scurried around the old boats along the coast.

Once in the clutches of the town or the sea, such children rarely returned home; many of them left on the large ships loaded with cereal and grains, headed for Europe.

At the beginning of this story, Ismaël is the only child left.

Ismaël’s “blessing” is his gift for composing poetry and songs, which also reminds us of the Orpheus legend:

His inspiration is completely natural, instinctive, and the novel thus deals with the concepts of creativity and inspiration as well: Ishmael continued singing, and his heart grew lighter, lighter within his chest, like a bird about to take flight. And a strange clarity filled his mind, the kind of clarity that exhilaration or delirium sometimes brings.… Never did the boy think about the words in advance: they came to life in him like mysterious birds to whom he only needed to give a little nudge, and the music that accompanied those words came just as naturally.

In many of Némirovsky’s works, she draws on the music and fables from her Jewish background, and her protagonist here does the same.

Ismaël earns money by going to bars where he composes and performs impromptu poems and songs. One evening, a nobleman hears him and is entranced. He introduces him to his lover, who Ismaël calls the Princess. She takes him to live with her, paying his family (who are delighted) and providing him with wealth and attention. He is a young adolescent and falls in love with her, which brings in the fairy-tale element. But unlike traditional fairy tales with happy endings, things begin to go wrong.

Ismaël has lost his gift. He reads the great Russian authors and finds himself extremely lacking compared to them. After many long months, the Princess summons him, and his father comes to bring him to her. His father remarks that he has cut off his peyos, the traditional long curls that observant Jewish boys always have — another symbolic reference to Samson and Delilah.

I don’t want to give away the whole story, but I will say that it is definitely worth reading!

Sandra Smith was born and raised in New York City. As an undergraduate, she spent one year studying at the Sorbonne and fell in love with Paris. Immediately after finishing her BA, she was accepted to do a Master’s Degree at New York University, in conjunction with the Sorbonne, and so lived in Paris for another year. After completing her MA, she moved to Cambridge, where she began supervising in 20th Century French Literature, Modern French Drama and Translation at the University. Soon afterwards, she was accepted to study for a PhD at Clare College, researching the Surrealist Theatre in France between the two World Wars. Sandra Smith taught French Literature and Language at Robinson College, University of Cambridge for many years and has been a guest lecturer and professor at Columbia University, Harvard and Sarah Lawrence College.