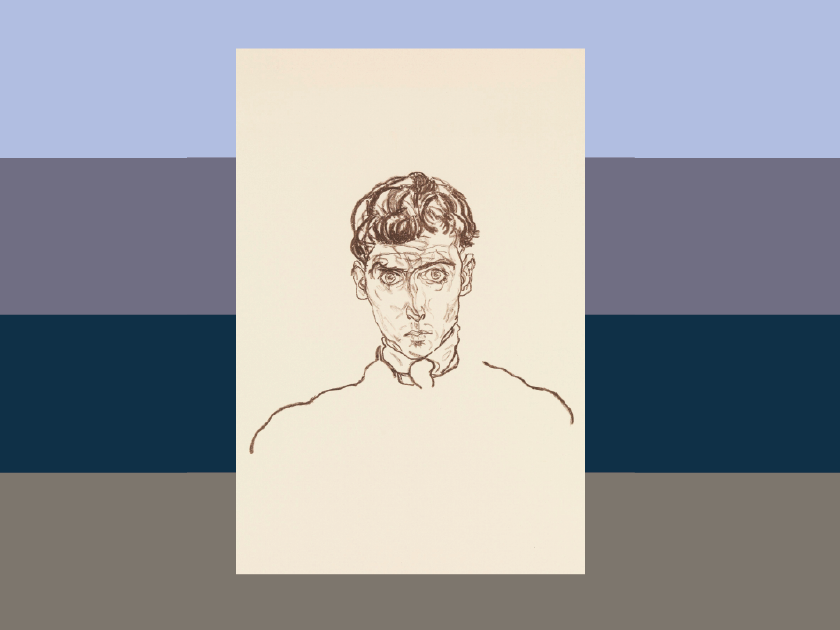

Portrait of Paris von Gütersloh by Egon Schiele

Bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Design by Katherine Messenger

Congratulations to the 2020 winner of the Paper Brigade Award for New Israeli Fiction in Honor of Jane Weitzman: Shimon Adaf, for Mox Nox, translated by Philip Simpson. This selection from the winning title can be found in the 2020 – 2021 issue of Paper Brigade.

The Paper Brigade Award for New Israeli Fiction in Honor of Jane Weitzman seeks to honor an outstanding short work or excerpt of Israeli fiction published in Hebrew. The goals of this prize are to introduce American readers to new Israeli writers; to help Israeli writers gain access to the American market; and to interest American publishers in publishing new Israeli fiction.

Shimon Adaf is one of Israel’s most innovative and highly acclaimed young writers, and Mox Nox shows him at the top of his form.

The unnamed narrator of the novel describes the events of one summer when, as a sixteen-year-old from a small Israeli town, he worked at a kibbutz factory. He recalls his dealings with two other boys working there, and with the factory’s secretary — a lonely woman who he suspects has romantic intentions toward his father. The narrator initially views his acquaintanceship with the secretary as an unwelcome imposition. But soon her profound interest in poetry and language prove to be the means by which he can free himself from the tedium of his life; ultimately, it will determine the course of his career.

In a parallel, present-day storyline, the narrator — now an established writer leading literary workshops for socialites — is drawn into a love affair with an older woman who undermines his certainties about the world and forces him to reexamine the events of his past. In the midst of all this, ghosts emerge from the fissures of everyday life, ghosts that he must confront in order to fulfill society’s expectations of a son, brother, and lover — while also surviving as a creative person contending with unintelligible traditions and the divine.

—Philip Simpson

By the age of ten, I had broken my left clavicle four times. The first time I don’t remember. I was nine months old. My mother says I rolled off the bed where I had been laid, and one of the pillows supposed to protect me fell down with me. I won a lot of quizzes in local competitions, my father’s face hovered over books in the evenings, some wayward radiance of the streetlights mingled with the light in the room; the picture in the deep recesses of my mind is still dark. I got used to answering. I traveled into the future, pushing my consciousness forward until I arrived. Every schoolboy knows that time is composed of tiny particles with empty spaces in between. I saw hailstones, I saw firestorms, cities smoldering, mountains turned into valleys. I saw rivers of tar, I saw limestone caves, flashes of unfamiliar beauty. The second time, I tried to catch a ball that was kicked to me too hard, my left arm was knocked back into the flesh; the clavicle collapsed. I went around with my arm in a stiff cloth sling that set the bone, painful and irritating. My sister had conjectures of her own. In the spring I found, in a pile of trash, a guide to programming, the ancient and primitive language of computers. I read it to the end. I imagined loops and subroutines, procedures on paper, games and strategies for creating obsolete functions. Although my father promised to buy me a computer, he went back on it, claimed he couldn’t afford one. I pleaded with my mother. I bathed in light, pensively, as the splendor of the world intensified around me, its clamor, too. My sister dragged me through a eucalyptus grove. In class I was promised a prize for a puzzle that I solved; on the appointed day I was too ill to go to school, and when I went back, the whole thing had been forgotten. There was a sharpness in the air, perhaps hours before the grove had been drenched by the rain. For many years, my father had been tormented by a cruel afrit in his sandcastle, until my mother rescued him with her spells and imprisoned the demon in a datestone. Two friends in my elementary school rubbed against each other in mutual masturbation, through their clothes, how dry is the mouth, but what about the pleasure. I fled from the synagogue and from my father’s wrath, I saw destiny written in the clouds. One endless summer, a snatched summer, in a playground near the municipal pool, I was thrown from a swing. I tried to break the fall with my hands and the clavicle went again. I moved around with my arm in a sling, and when they removed it, a white stripe was revealed in the golden skin. My body heat was rising all the time, viruses came, and fevers, strange swellings, moisture, phlegm. They asked me, a giant and a dwarf are walking through the forest, in the distance they see a light that is turned off and turning off — who notices it first? I devoted a month of my life to studying the mysteries of kung fu, I decided to invent a style of martial arts that imitated a different animal. I longed for the peace buried in trees. The rustle of the leaves grew louder until I could hear nothing else. I stood in the middle of a swarm of ants. I counted them until I felt them swarming up my legs; if I had looked up at that moment, a polished sky would have been revealed to me.

I read until there was no point in reading any more. The winter came, the winter went, the rain fell vertically. I stole more books in dead languages, celestial bodies weighed heavily on my shoulders, in the gloom, syntactic variations glowed, superior tropes, hexameters, the anapest and the dactyl, the amphibrach, which is not intended for our kind. O tempora, O mores, somebody said. I checked in the dictionary for the meaning of the word ophel — I found it meant a donjon. I jumped down from the washing machine on the enclosed balcony. The clavicle gave in, this time with a dry, explosive sound. For some reason the drum of the machine was throbbing, perhaps it had started a spin cycle. I said my father was a god who took on different guises, my classmates mocked me in the playground, I asked my mother for proof, and in the end Dad let me drive his sun chariot. After I broke my clavicle in the school corridor, the doctor who checked my medical history found ailments and failures of the immune system, found the reason for my afflictions. The clavicle never healed properly, and was doomed to be a perpetual barometer of atmospheric changes. A dull pain was ignited in it; its convexity was too convex, threatening to break through the skin. Sometimes it attracts attention, although I’m not in the habit of walking around in public without a shirt. I buried a coin in the sand to preserve it, and it lost its value the following day. In eleventh grade, a student said, it should be, one hand shakes the other. One hand washes the other, the teacher corrected him. But that doesn’t make sense, he protested, what does washes mean here, shakes is more logical. Washes, washes, the teacher repeated. I said, it’s a literal translation of a Latin motto, Manus manum lavat. The teacher looked at me. It was my mature consciousness, having crossed the river that no one enters even once, speaking from my sixteen-year-old throat. They called the little finger auricularis, from auris, meaning ear, because they used it for scratching, I whispered, the infamis, or wicked finger, we didn’t invent the language of the body. When I was sixteen, my father got me my first-ever job. Whole nights I spent staring into the darkness. Something was coming — I didn’t know what.

___

My father already sensed that my faith was faltering, I went to the synagogue under his watchful eye, but he guessed the questions that had begun running around in my brain, the doubts. I cast hollow glances at the walls of the synagogue, kissed the curtain of the ark at the end of Sabbath morning prayers with dry lips and made no appeal. He said, what are you going to do all summer, just hang around again. Anyway, we can’t afford to finance you, you’ll soon be responsible for yourself. I knew what was hidden behind his words. Now that they were subsidizing my sister’s education, everyone had to contribute. He talked to some people at the kibbutz factory where he worked in a facility for dehydrating vegetables. The simple blue laborer’s overalls, working clothes they were called, were covered with colorful powders when he came home. He said, I’ve fixed up a job for you in the factory tool shop.

I cast hollow glances at the walls of the synagogue, kissed the curtain of the ark at the end of Sabbath morning prayers with dry lips and made no appeal.

It was hot. Early July. Not so hot at the time I had to wait for transport. My mother roused me at five in the morning or perhaps earlier. Somewhere the sun was streaming on the launchpad, only the first rays, breathing life into the shadows of the day. My mother whispered my name. I jumped up. My sleep was sweaty enough. She went back to bed and I went outside after the morning prayers. Always the same, the chill every morning; always the same, the dryness of the desert. I went up the road, turned with the bend, and the transport, a big vehicle — in my memory, it was smeared yellow with two horizontal purple stripes — took me on board. I was wearing overalls like all the others. Deep blue, close to black, peaked cloth cap. The driver stopped at the gate of the factory. Previously, the landscape had flashed by the windows; still barely awake, the trees huddled together in dark masses, standing out against the light, my eyelids sank, silence in the interior of the bus, only the exertions of the engine, and I felt tired looks gliding over my face, someone wanted to know if this was my first day, if this was my job for the summer, if I was just a new worker, in which department was I destined to serve out my time. Someone wanted to say, get out of here, kid, why do you need this shit, but kept quiet.

The driver showed me where to go. My father was in charge of the department, in other words, he was responsible for it, in other words, he was intimately acquainted with the machines, knew every detail of their operation, the screws threaded into nuts, the gyrating belts, setting the ribbons in motion, clumsy motherboards, if there were motherboards, flickering lights, clocks and dials, stress in the air, and despite all this, he received a simple worker’s wage; the title of manager, the magical power inherent therein were denied him. The department was the last link in the chain of dehydration. The vegetables went out from there flattened, woody, sapless, packed and ready to be compounded into fast foods, blended by the alchemy of capitalism, and to come back to life in microwaves, in convection ovens. My father breathed into his lungs all the dust and the particles emitted in the process, and sometime — not now, in a few years — he’ll go down with a stroke, a hemorrhage of contaminated blood.

He was waiting for me, at the end of his night shift — responsible or not, he still had to work nights — and asked, after a cursory inspection, did you have time to pray? Just the morning blessings, I replied. He said, come on, what’s the matter with you, are you not awake yet, and he led me to a tin shack, which accommodated an improvised office with a desk, a filing cabinet, and no shortage of paper, and handed me the tallit, the tefillin, the siddur. And after this you can make yourself coffee or something, he said, pointing to the coffee corner, and come and look for me.

The smell of the tool shop struck me at the entrance, the screech of scraping metal and the hissing of the cooling water, and the smell of oil, heavy and sweet, like incense, and other, cold smells, of metals lying in wait for their forging, iron ingots. And from the other side, which opened to a neglected yard, blew a vapor of cigarettes, which were forbidden in the confines of the tool shop, with the flammable welding gases, oh, and the smell of fire, not burning, the smell of the precision flame, and the smell of men, the collective presence of bodies and sweat, alarmingly earthly. But it is the brazen way of smells to store up memories. This will be the smell of happiness. As I pass through the fringes of great cities, in streets of industry, avenues of molten steel, excavations, under the weight of the sun, by garages and factories and power stations, this will be the spark that whispers in the soul that everything is still possible. And my father introduced me to the foreman of the tool shop who asked if I had any experience, if I had worked in a similar environment, in school perhaps. Yes, all the boys were required to take classes in soldering, and before that, carpentry, and I had soldered a candlestick for my mother and constructed a chopping board. I wasn’t good at this, the only profession in which I came close to failure. In physical education, too, only at sprints did I seem to excel. I wasn’t so good at the shot put, the triple jump, the high jump, all those frolics, but I nodded with what seemed to me an enigmatic smile, and looked in wonderment at all the other men, crouched over vises, beating out sheets of tin, their eyes calculating the dimensions required, unrolling measuring tapes, entering and leaving. Don’t worry, said the manager, a kibbutznik whose office was up the stairs, its little windows overlooking everything going on down below, you’ll have company. Two boys your age, sons of workers in the factory, will be helping here during the vacation. We won’t leave you alone.

____

I stand before the door of the apartment, put the bags down on the floor, fumbling with the key in the lock, the teeth consumed by rust or by overaggressive use, the metal is tired, close to breaking. I go inside, the light that I left on when I went out, a whispering neon tube, gives the void an extraterrestrial glamor even at midday. I have stumbled upon a habitation that isn’t mine. Absently, I arrange the groceries in the fridge. I would like to be filled with wonderment, not the twisted razor of anger. Later I will find the shampoo that I left crammed between two bottles of water. Before I went out shopping, I was met in the foyer of the building by a courier, who asked if I knew a certain tenant. I answered that although it was me he was looking for, whether I knew myself was a different kind of question. He handed me a small package, I opened the wrapping and peered inside. A greenish pamphlet, no mention of the sender. The courier was already turning to go. Wait, I stopped him. He put on his helmet, his voice split my reflection on the face mask, muffled: what. Who’s responsible for sending this. He shook his helmeted head, don’t know, if it isn’t written on the envelope, you can ask at the office.

I peered inside again, put my fingers in to take out the pamphlet, and my fingers met a flexible cord, fibrous but solid underneath. I took hold of it. When I withdrew my hand, I saw a tail, the tail of some rodent, a mouse, perhaps a rat. I dropped it on the floor in disgust, stuffed the envelope into the mailbox, a scratched and battered tin, and went to the grocery store. The grocer, his eyes glued to a giant screen with reports of a war on some continent or another, growled the total. I groped for the remaining coins in my wallet and said, we’d better cancel this item and that one. He said, take them anyway, no harm done, they’re on sale. When I returned with my purchases, a cat came running out from the entrance to the building with something quivering in its mouth, I couldn’t see what, and already it had jumped into the sandy back garden, girded by bushes with flowering blossoms, thick stalks stretched out to suck. The package was gone from the mailbox, and needless to say, there was no sign of the contents, either.

I go to the windows, which I had closed before going out, an anorexic girl is walking in the street. I follow her skeletal figure with my eyes until she disappears. The film of sadness that she arouses in me remains, pinpricks in the hands. How contemptible are our ambitions to survive. How terrifying the ghosts that they engender. The streetlights cast thin shadows. The clouds go on drifting. On the electric cables, the roosting place of doves, the crows compete in their usual style over living space. I migrate to the writing desk. The computer screen is switched on. I swore to myself that I would make progress today writing one of the metaphysical stories, as a brainless critic described my novellas. Or at least do some cutting. Who was it who recommended that in order to write good books, one should turn the pen at regular intervals and use the other end, the end opposite the tip. Definitely the poet Horace. If it were possible to create a parallel for piety in the teaching of writing, Horace would have done so. I check my emails. Nothing. What is new in the cultural rubrics of different sites, the gossip, I drift to a site tracking booksellers in the US. There is something reassuring in the indifferent figures, and in the forces behind them, with their refusal to reveal themselves, with their constant peeping out from the crevices between the numerals. I have no choice but to return to the orphaned beginning.

Shimon Adaf was born in Sderot, Israel, and now lives in Jaffa. A poet, novelist, and musician, Adaf worked for several years as a literary editor at Keter Publishing House and has also been a writer-in-residence at the University of Iowa. He leads the creative writing program and lectures on Hebrew literature at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Adaf received the Yehuda Amichai prize for Hebrew poetry (2010) for the collection Aviva-No; the Sapir Prize (2012) for the novel Mox Nox, the English translation of which, by Philip Simpson, won the Jewish Book Council’s 2020 Paper Brigade Award for New Israeli Fiction in Honor of Jane Weitzman; and the I. and B. Newman Prize for Hebrew Literature (2017).