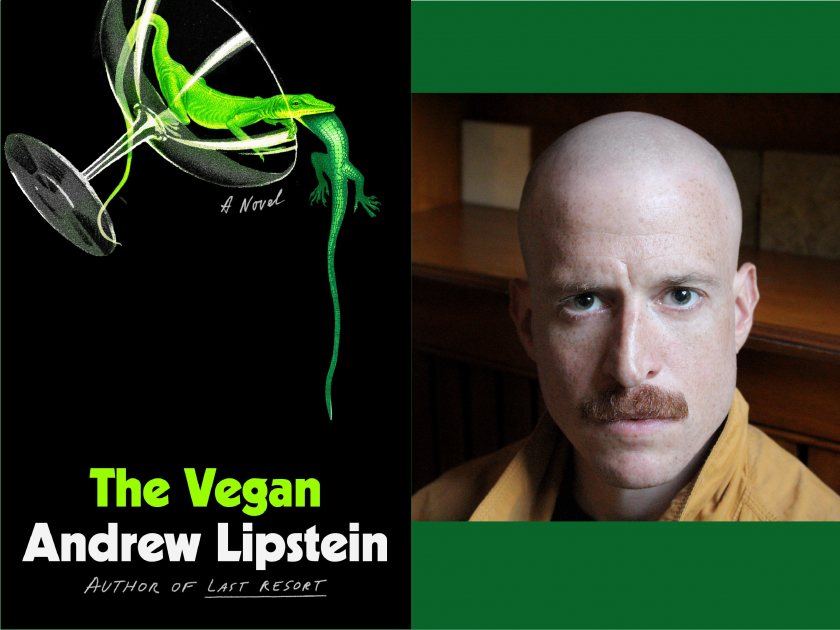

Author photo by Mette Lützhøft Jensen

Chloe Cheimets speaks with Andrew Lipstein about his new novel The Vegan, exploring competitive morality, the power of money, and the role of guilt in our contemporary world.

Chloe Cheimets: Herschel Caine is a partner in a quantitative hedge fund. The Vegan deftly explores the competitiveness, paranoia, greed, and single-minded mathematical brilliance of this world. What drew you to hedge funds, and algorithmic trading in particular?

Andrew Lipstein: I love money. I love how it acts in society as a “score” that no one can disagree with. I think that’s why there’s often so much wickedness surrounding it; its simplicity and truth is so alluring that many of us believe it can wash away all of the impurity involved in its acquisition and use.

I also believe — as do many others — that there will be a time not too far in the future when machine learning (as in, AI) will be able to reap immense profits from the public markets. We are so used to equating value with production, and even contribution to society, but there’s an entire industry built on smashing this equivalence to smithereens. As part of my research for The Vegan, I interviewed a handful of quant hedge fund CEOs and analysts. I wanted not only the industry jargon and technicalities but their point of view, their humanity, their way of seeing right and wrong.

In a more oblique sense, I’m attracted to high finance as I’m intensely interested in how money can act as a metaphor for morality, and vice versa. More and more, it seems, we think of our own goodness as something with a number attached to it, as if it can go up and down like our bank account, as if we can make up for a moral deficit in one part of our life by attaining a surplus in another. Even more fascinating, I think, is how morality — like money — is becoming defined by its value relative to those around us. If everyone in the world gets a thousand dollars, no one becomes richer. Morality doesn’t have to be like this — communality is not a fixed value — but that’s what I see today. We profit, so to speak, when we find moral flaws in others. We build our own moral riches atop those with deficits (as we see it), but the great irony is that morality is subjective, and those we find morally bankrupt may think of us in the same way. So we all can feel like we’re getting richer while our moral economy is actually driven by the devaluing of everyone else.

CC: At the beginning of the novel, Herschel Caine has recently purchased a townhouse in Cobble Hill. The moral and social anxieties of the contemporary Brooklyn upper class are an important backdrop to this story. How important was setting for you while writing? Do you see this, at least in part, as a story about Brooklyn?

AL: I can’t think of a better illustration of the concept of the narcissism of small differences than Brooklyn neighborhoods. To mostly anyone outside of the city, brownstone Brooklyn is one place. But when you spend some time here — in the past few years I’ve lived in Clinton Hill, Park Slope, and Cobble Hill — you sense slight discrepancies in the cultural fabric, even tweaks in moral priorities. Cobble Hill is well-to-do, it’s prosperous, but in a nervous kind of way. The stores that pop up more and more — high-end clothes boutiques, Warby Parker, home goods purveyors with wares whose primary purpose is to seem expensive — satisfy a need to fit in, to buy in, to show you’re not an outsider. It’s funny for a neighborhood and its denizens to feel so, well, unneighborly. It’s also deeply sad and, I think, indicative of something global and timeless. If wealth and financial comfort lead to existential detachment and fear of our fellow man and his opinion, how else can we see money but a zero-sum game?

Is it a story about Brooklyn? Like all stories, mine is about a time and place. But I hope it’s also about something more permanent.

More and more, it seems, we think of our own goodness as something with a number attached to it, as if it can go up and down like our bank account.

CC: As the story progresses, and Herschel sinks into guilt and desperation, the writing stays extremely close to Herschel’s minute by minute perceptions and physical sensations. It’s a deeply sensory and immediate book. How did you land on this style of storytelling?

AL: We often think of morality as logical, intellectual, and analytical. We make moral decisions. We are moral actors. And yet, our moralities often speak to us through bodily reactions and emotions: we become disgusted by those who violate our morals, and we may even fall in love with someone via their goodness (however we, individually, define that word).

This contradiction — morality can be both rational and carnal — is similar to the mutually exclusive ways we view our species: we are animals, yet we are not animals. We consider ourselves like them when it suits us, and we don’t when it doesn’t. This hypocrisy shows itself most in our dietary practices. Many westerners eat cow and pig and chicken but not horse or dog or cat. The first three are delicious, the second three repulsive. These choices are too contrived not to be cultural, yet we pretend they’re innate. This is like all of morality: we must pretend it is something like truth, but it is, of course, nothing at all.

CC: Herschel develops an aversion to eating meat and animal byproducts. Can you speak on Herschel’s veganism and its centrality in the story?

AL: Early on in the book, Herschel crosses an invisible boundary, and believes — or makes himself believe — that his neighbor’s dog can recognize morality, specifically Herschel’s guilt. It’s a simple idea, merely a seed, but it has the power to sprout a radical worldview. For Herschel, this starts with going vegan — not radical at all, given ten million Americans have made the same choice. But after every step up his ladder of virtue, Herschel finds himself in rarer company, and soon enough all of humanity is beneath him. This is what is so disorienting (and dangerous) about the modern instinct to think of morality as a competition: what existed to bind us together can make us utterly alone.

CC: This book has a wonderful preoccupation with the meaning and etymology of words. Herschel calls it a “mistrust of language.” Can you talk about Herschel’s interest in language? As a writer, do you share his mistrust?

AL: Yes, haha. I do. I believe language is one of the most, if not the most, malignant actors on human connection. Like a cancer, it absorbs all of the thing it acts on — communication — while distorting it, ruining it, making it its own.

At his most deranged, Herschel decides he and his wife should conceive a child during a weekend devoid of words. We find the idea ridiculous, but reflexively, defensively. Why is that so absurd to us? What part of ourselves would we have to abandon to accept that idea, and why are we so afraid to let it go?

But Herschel’s interest in (disavowing) language is also selfish, of course. Language helps him describe to himself what exactly he’s done to Birdie. It solidifies the whirl of reality into neat logical blocks. Only by rejecting the crystallizing force of language is he free to manipulate the facts as he wishes — or disregard them entirely.

CC: Guilt, and its reverberations, is a major theme of this novel. Guilt is also a trope of Jewish life. Do you see this as a Jewish story? How does Herschel’s Jewishness influence his choices in this text?

AL: After I wrote The Vegan, over lunch, my editor asked me why so much of my writing comes back to guilt, in a way that I took to mean: Why do you feel so guilty? He was right. I’ve always felt guilty, even as a young child, even when I had nothing to feel guilty about. It’s a Jewish trope, of course, the guilt your mother gives you, the handwringing, the rumination. But it’s more than a caricature: guilt, at its core — taking responsibility, taking on the burden of ownership for your actions, intentional and otherwise — is a very Jewish concept. Jews are obsessed with law, with sorting out liability and justice, with measuring crimes and their punishments. In this way, The Vegan is very Jewish.

But Herschel rejects his own Jewishness. Or rather, he employs it when it benefits him and discards it when it doesn’t. He uses it to paint himself as a victim, yet calls Jewish law “arbitrary, outdated, and bizarre.” He blames the Jews, in part, for the contrivance of written language, yet laments that his gentile neighbor — just by dint of his hairstyle, mannerisms, and wall art — is appropriating Jewish culture. In this way, his Judaism is just another “emotional ingredient” of his life, in the way I use that term in this passage: “I considered it a skill, even, this ability to cleave cause and effect, to chop up the emotional ingredients of my life and use them as I wished.”

CC: Your debut novel, Last Resort, came out in 2022. Your third novel, Something Rotten, comes out in 2025. This is an amazingly prolific moment for you! What’s your writing process like?

AL: It’s funny, when I wrote Last Resort I believed in a kind of whimsical approach to inspiration: catching it, courting it, writing whenever it struck me — at whatever hour that happened to be. With The Vegan, I wrote feverishly over the course of a winter, hitting word counts I’ll never approach again. Then I had a child, and time became in short supply, and now I’m more of an “ass in the seat” writer. Early in the morning, five days a week, without fail (when I’m working on something), I sit down and write, producing 500 to 1000 words. I wish I’d done this earlier. By writing less each day (and thus having more of it to think about what I want to write the next day) I’ve found I have more to say than I have time to write — all a writer could ask for from the gods of production, really.

Chloe Cheimets has an MFA in fiction from The New School.