I am the only one who gets off the train at Tōno. Disabled since birth, I’ve come to this rural Japanese outpost to research disability representation in the famous folktales of the region.

The most popular character of the Tōno legends is the mischievous kappa, seen all over the town: on postboxes, in souvenir shops, and even at the koban, the police box. The kappa is somewhat frog-like and has long skinny limbs, webbed hands and feet, a sharp beak, and a hollow on the top of its head. At the Tōno City Museum, I learn about the belief that women who become pregnant with a kappa’s child give birth to deformed babies. According to the tale, passed down for generations, these babies are hacked to pieces and buried in small wine casks.

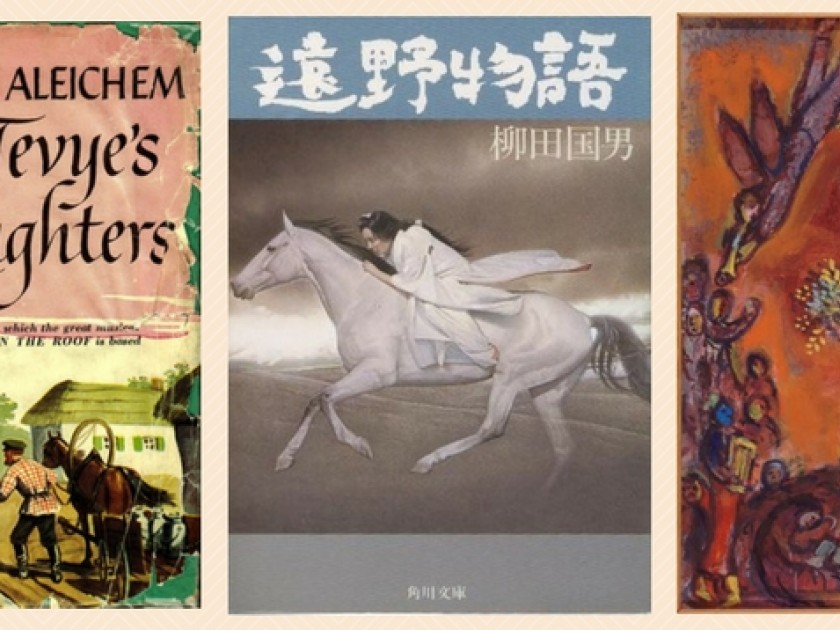

As often happened during my time in Japan, I did not expect to find what I found in Tōno. I left the city haunted by a tale unrelated to my research, which reminded me both of tales by Sholem Aleichem and the paintings of Marc Chagall.

First, the tale: A girl falls in love with her family’s horse. Day and night she visits the horse in his stable. The girl’s father becomes worried about his daughter’s attachment to the horse, but no matter what he says the girl continues to visit the horse. She is discovered spending her nights sleeping with the horse.

The father takes the horse out into the forest and kills it, hanging it from a mulberry tree. When he returns to the house, his daughter is gone; she cannot be found anywhere in or near the house.

The father returns to the forest. He stops in his tracks. He sees his daughter now hanging with the horse from the tree. Before he takes another step, the horse rears up and ascends into the sky, carrying the girl with him to the heavens.

What is it about this tale of forbidden love in the shadow of loss that connects to my Jewish soul?

This story reminds me of Tevye’s reaction to his daughters’ marriages outside the conventions of their shtetl in Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye’s Daughters. Tevye’s eldest daughter, Tzeitel, wants to marry for love rather than through the traditional matchmaking. This, Tevye figures out how to accept, allowing the marriage without compromising his values.

However, it is the love of Chava, his third daughter, for Fyedka, a Ukrainian Christian, and her conversion to Christianity, that puts Tevye to the test. In the Aleichem tale, Tevye does not pardon Chava’s defection. Tevye pronounces her dead and observes shiva, until Chava repents and returns to her Jewish home. Those familiar with the story from Fiddler on the Roof, the beloved Broadway musical, might be confused because this resolution was changed for the stage. In Fiddler on the Roof, Tevye eventually accepts Chava back into the family and, as the rest of his family leave Anatevka for America, he watches his daughter depart with Fyedka to Poland.

In the Tōno tale, the father’s reaction to his daughter’s forbidden love is similar to that of Aleichem’s Tevye. But what if the father reacted more like the Tevye in Fiddler, finding his way to accept his daughter’s nontraditional love? What would have been lost? He might have saved his daughter’s, and the horse’s, life.

And what to make of the vision of the flying horse, carrying his daughter away from him, up into the heavens? For me, Chagall’s flying figures and animals, especially in “Song of Songs IV,” a 1958 illustration for the Old Testament, further illuminates the Tōno tale. In the painting, a flying horse carries a newly married couple into the sky. Nowhere in the text of the “Song of Songs” is a flying horse mentioned. Nor are upside down birds, also included in Chagall’s painting. Here, Chagall represents the spirit of the bride and groom’s marriage as spiritual ecstasy freeing them from the scene below. An angel trumpets their celestial ascension in a sky neither dawn nor sunset, with both sun and moon.

Relating Aleichem and Chagall unlocks for me deeper meanings that answer why the Tōno tale still haunts me. Love can be both a means to freedom and to separation, sometimes at the same time. In love, we can find a freedom both of and from ourselves. But it is also love that can separate us from family, friends, and the culture or society from which we come.

The price of forbidding — whether through love, or by having a body that looks different — is a theme central to many Tōno tales. Like the kappa tale, in which deformed babies are killed and buried, the forbidden love of the daughter and her horse has serious repercussions. This, too, is what becomes of breaking social barriers. At the heart of these stories are both the ecstasy of, and the price we sometimes pay, for love.

Images (LTR) via: Crown Publishers, Kadowaka Shoten, and WikiArt

Kenny Fries’s new book is In the Province of the Gods, which received the Creative Capital literature grant. His other books include The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory and Body, Remember: A Memoir. He edited Staring Back: The Disability Experience from the Inside Out. He was a Creative Arts Fellow of the Japan‑U.S. Friendship Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts, and twice a Fulbright Scholar (Japan and Germany). He teaches in the MFA in Creative Writing Program at Goddard College.