Courtesy of the author; “Panama Hats on their way through the Culebra Cut to Maduro’s Souvenir Store.”

I’d like to talk to you about letters. I am old. I am trying here for shorthand. The word “old” defines me as having lived in times when people communicated over long distances with pen on paper and on manual typewriters: Olivettis, Royals, and Selectrics with the silver typeball. I have hand-drawn notes I made for my mother and father (mami and papi) for birthdays and hospital stays, sweet girl that I was, adoring my mother when she left home for sojourns in psychiatric institutions in the United States — twice in my childhood. I wrote her letters then, missing her, signing “te adoro,” trying to express an amorphous feeling, not believing it was reciprocated.

Author’s Mother

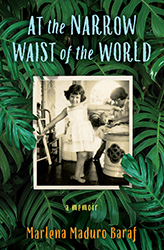

I’ve written a memoir about her — my need to love her, and the distances I had to cross to be close to a woman troubled with overwhelming anxiety that left little room for me, or my sister and brothers. It is set in Panama and in the U.S. after I leave for school in my teens.

I have a box — a medium sized cardboard box filled with letters written in untidy longhand that I received while in school. I kept them all. They landed in my mother’s apartment in Panama for safekeeping. A mother’s story — her child’s belongings saved — though my stamp collection was lost.

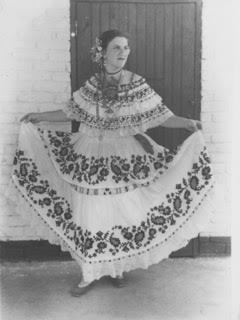

Author’s Aunt in traditional Panamanian Pollera

My memoir, At the Narrow Waist of the World, relies on my own vivid memories and a few tender stories from my siblings via long-distance phone calls. I read histories and old newspaper accounts about my sprawling family — Spanish-Portuguese Jews who established themselves in Panama in the mid 1800s. I spoke with her long-time psychiatrist. I also relied on letters I discovered in that cardboard box.

When I traveled to the U.S. for school in my sophomore year of high school, armed with coins, I communicated with my family while standing at public phone booths with doors and by way of letters on blue par avion paper, light as feathers. I reported my news, conveying my nostalgia, holding on to the lifeline of my very large, extended family who were close-knit within a Catholic society that also celebrated family. There were so many firsts in those first years in the U.S. — field hockey, The Scarlet Letter, snow. I visited the Jewish home of my new suite mate on my very first Thanksgiving and heard Jewish prayers at the table. I felt a deep connection and understood that I was not alien in a foreign land. I discovered letters from tías and tíos, hermanos, primos, boyfriends, my abuela — even letters from mami who behaved like a responsible parent, caring that I’d have warm enough clothes in the igloo of the American Northeast.

I visited the Jewish home of my new suite mate on my very first Thanksgiving and heard Jewish prayers at the table. I felt a deep connection and understood that I was not alien in a foreign land.

When I experienced depression in my last year of high school and first years of college, letter writing — in the rare times I did it — was a lifeline to feelings. I still have some of the letters — did I never mail them?

I found the brown, cardboard box when looking for a batch of letters that I knew I had, letters papi wrote to mami when she was a patient in the Institute for Living in Connecticut. These were the last of many that he wrote to her before he died, which came back home with mami when she returned to us. I was eleven. My father had been an insurance man, a reader, and an introvert. “My whole attitude towards life is changing,” he wrote. “I don’t know what it is. While before I held my feelings in, now I surprise myself by coming out with it. I feel more confidence, my mental ability, my complexes. I can sell ice to the Eskimos! Will be a big shot before long if I keep this up.”

This letter was mailed in August. He died in October. The poignancy still breaks my heart.

A letter from my grandmother asked why my mother still loved the American man from the Canal Zone that she married after my father passed away. A man who beat her when he was drunk. Did I know why mami still loved him?

Letters sharpen the features of individuals in my family and record the power that community can have in sustaining us. I see my grandmother, her clear blue eyes. She is looking up into my face, begging me to explain her own troubled heart.

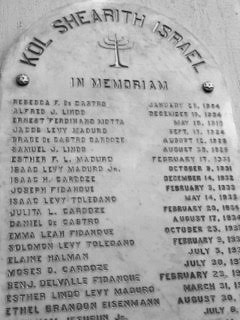

Tablet from author’s temple Kol Shearith Israel, including author’s great grandmother Julita Lindo Cardoze

I see my grandmother, her clear blue eyes. She is looking up into my face, begging me to explain her own troubled heart.

In my senior year of high school, I wrote to one of my more serious tios. “I can’t get through a kind of barrier that I put up or somebody puts up. Am I strange?” I asked. “Is it wrong to like to be alone most of the time?” This was the uncle who always made the Minyan at our temple and conducted services with other tios year after year in the absence of a rabbi.

I found his response in the box of treasures. “Since your father died, I have hoped to be able to fill that role for you, and now you have given me the opportunity. Both tia Connie and I love you as much as we do our children. So as part of this family I’ll talk to you as I would to them.” He was trying to lift me up during those confusing years.

Author with husband and grand nieces in Panama

Letters are artifacts of my past. In those records I discover, so many years later, who I was as a girl, and the dynamics of family.

I wonder if the writing of memoir is not another form of letter writing — exposing the precise image and feeling, sorting out the feelings, celebrating them. This is what drives us and we should not be ashamed.

Marlena Maduro Baraf has a knack for raising orchids. She immigrated to the United States from her native Panama, and her writing is colored by this dual identity. She has been interviewing Latinos from all walks of life for a series of articles titled Soy/Somos, or “I Am/We Are.” At the Narrow Waist of the World, chapters of which have been excerpted in Lumina, Streetlight Magazine, Blue Lyra Review, and the Westchester Review, is her first published memoir.