Growing up, I was the only Jew I knew with a Christmas tree.

My mother — who is Italian American and converted to Judaism for my Dad — decorated the tree in blue and silver, topped it with a six-pointed star, and called it a Hanukkah bush. But anyone with eyes could see its true nature — conifer, conical, and comically erected through the last week of December every year.

And yes, it presided over piles of presents on the morning of December 25th.

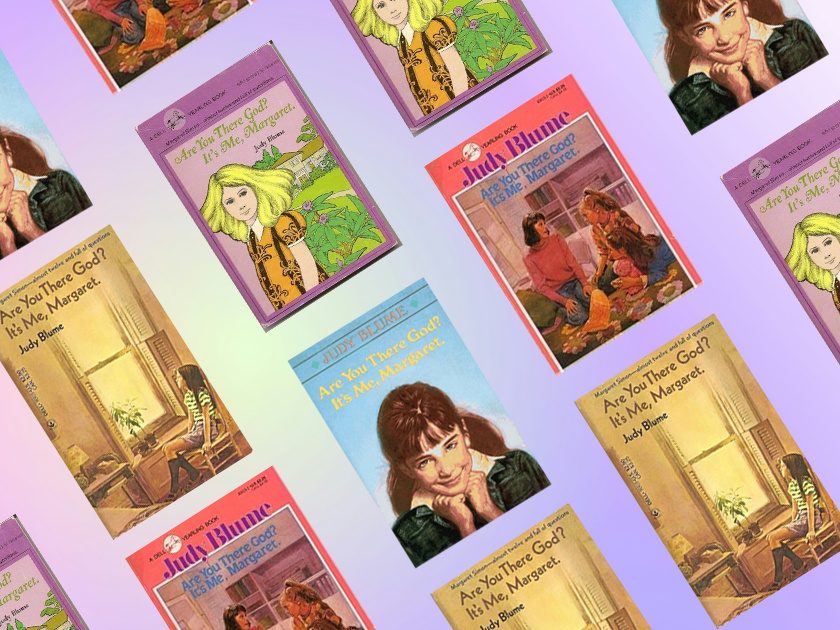

Living in suburban New Jersey in the mid-1980’s, I didn’t know any religiously blended families like mine. So imagine my surprise when, around the age of nine or ten, I opened up a scuffed-up purple paperback with a wistful-looking blonde girl on the cover. It was called Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. I wasn’t convinced it looked interesting but at that age, I read anything I could get my hands on.

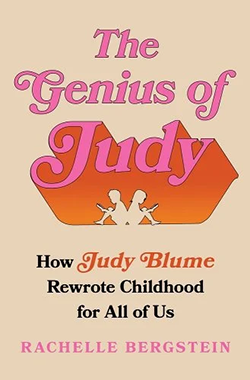

I was about to embark on a journey, one that has brought me to my forthcoming book The Genius of Judy: How Judy Blume Rewrote Childhood for All of Us.

“Are you there God? It’s me, Margaret,” the first line read. “We’re moving today. I’m so scared God.”

Was this some sort of religious book? I wondered. Not my thing, but I kept going.

Today, Judy Blume’s 1970s classic is best known for its honest discussions of puberty and menstruation. Generations of girls grew up wondering if we could rush along our development by swinging our arms and chanting we must, we must, we must increase our bust!

Yet those threads weren’t what grabbed me as a first-time, pre-adolescent reader of the book. Back then, I was fascinated by a scene that took place in chapter five.

Eleven-year-old Margaret has made new friends in the fictional town of Farbrook, New Jersey. They’ve formed a secret club, called the PTS’s (short for Pre-Teen Sensations). As they’re working out the rules of the club — going by snazzy aliases, maintaining lists of their crushes in a “boy book” — one of the girls asks Margaret if she goes to Hebrew school.

Margaret responds no, and that she doesn’t go to Sunday school either. “I’m not any religion,” Margaret admits after the girls press her.

This makes her an anomaly and the PTS’s want to know everything. “See uh…my father was Jewish and uh…my mother was Christian,” Margaret stumbles to explain. “My mother’s parents, who live in Ohio, told her that they didn’t want a Jewish son-in-law. If she wanted to ruin her life that was her business.”

Her parents eloped, she tells her new friends. And given all the trouble religion caused in their relationship, they decided to leave both their faiths behind.

This wasn’t my situation. Technically we were Jewish, Hanukkah bush notwithstanding. Unlike Margaret, I did attend Hebrew school. I celebrated the Jewish holidays with my Dad’s family and Christmas and Easter with my mom’s side, who were all still varying levels of practicing and non-practicing Catholics. Nobody seemed to have much of an issue with the whole thing.

I related to Margaret’s feelings of otherness as she stumbled through telling her friends that she had no plans to join the local JCC or YMCA.

And yet, I still felt a little bit different from my peers. Celebrating Christmas with a last name like Bergstein was perfectly fine within my extended family, but I sometimes found it hard to explain to my playmates and their parents. Questions were asked. Eyebrows were raised. The community I grew up in wasn’t the most diverse or frankly, open-minded, back then.

I related to Margaret’s feelings of otherness as she stumbled through telling her friends that she had no plans to join the local JCC or YMCA.

These scenes of Margaret navigating her family’s religious background made me feel seen.

Judy Blume’s books are so special because they tackled topics that very few other authors were bringing up with kids at the time. That includes the bold subjects she’s become best-known for — puberty, masturbation, and virginity — and also other less-discussed issues that arose as families got more complicated in the 1970s and 1980s, like divorce, disability, racial discrimination and yes, dual-faith homes like my own. In The Genius of Judy, I explore how Blume’s honest storytelling shaped her powerful legacy.

Blume took on these subjects because she saw the world changing around her. Even though she was raised Jewish, she recognized the way that religion might be an obstacle for a kid like Margaret, whose parents had been hurt by it and vowed to leave it behind. To tell Margaret’s story, Blume drew from the private relationship with God she herself had as a child. She worried her beloved father (a dentist named Rudolph Sussman, who she affectionately called Doey-Bird) would die young of a heart attack like two of his older brothers. And so she prayed for him, in a secretive, ritualistic way, outside of the confines of any organized religion.

As a writer, Blume understood that children were more complicated than many people gave them credit for. They could get into fights on the school bus one morning and think critically about God that same night before bed. She made so many young readers feel that their experiences were normal.

After all these years, I’m still grateful for Margaret — and for Judy.

The Genius of Judy: How Judy Blume Rewrote Childhood for All of Us by Rachelle Bergstein