Not long ago, I was having shabbat lunch at my local Chabad House. I’m rarely at that table without meeting another rabbi from some far-flung part of the globe— I’ve even met the rabbi of JFK airport — but never have I met a more interesting rabbi than I did on the shabbat in question.

His name, of course, was Menachem Mendel, and his Chabad House was in Hobbiton.

That’s right — Hobbiton. In Middle Earth.

It wasn’t a bad gig, he said. The hobbits were generally pretty respectful, if a little suspicious, and there were always dwarves coming through on their way to Bag End or the Blue Mountains. You could always count on dwarves to at least put on tefillin.

I’m kidding, of course, but I’m also making a point, and it’s this: Jews and fantasy go together like challah and wine. It just makes sense.

And maybe there’s a reason. All three of the foundational texts of contemporary fantasy—The Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, and the Harry Potter series — have a kind of Jewishness somewhere deep in their source code.

Tolkien’s dwarves are famously Jewishly inflected. Tolkien himself acknowledged that Gimli’s battle cry at the Hornburg — “Baruk Khazâd, Khazâd ai-mēnu!” — is essentially Hebrew. And I was surprised and thrilled to find on my most recent reread that the Elvish name for Tom Bombadil — that reclusive, joyous, cosmic outsider, the closest thing to a Hasidic rebbe in Tolkien — is Iarwain ben Adar. Tolkien purists will insist that despite appearances, this name has no etymological connection to the Jewish patronymic form or the month in which Purim occurs. But I believe that there’s at least a small measure of thematic rhyming at play: a sort of subcreative hashgocha protis, or divine providence.

Jews and fantasy go together like challah and wine.

The Jewishness in Narnia is a bit more difficult to detect. The Chronicles are a profoundly Christian corpus; in 2010, the Jewish Review of Books even ran an essay by Michael Weingrad entitled Why There is No Jewish Narnia that decried the fundamental goyishness of the fantasy genre as inspired by the indelible Christianity of “medieval nostalgia.”

It’s true that there’s no Iarwain ben Adar to be found in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, but I’d argue that the fundamental Christianity of the work creates a very Jewish negative space. Narnia is a world in which there is a great leonine Christ, but no sign of the Jewish Jesus; a castellated medieval-ish capital — Cair Paravel — with no Jewish quarter.

But there is no Christianity without Judaism. Any picture of the medieval world, even if run through the fantastical filter, is either incomplete or inaccurate without the presence of Jews and Jewishness somewhere, and it would be hard to believe that Oxford don C. S. Lewis was unaware of this fact.

But of the — excuse the expression — holy trinity of contemporary fantasy works, I’d argue that Harry Potter is the most Jewish[1]. I don’t refer here to Anthony Goldstein, the Jewish Ravenclaw prefect and Dumbledore’s Army member. Nor do I refer to his distant relations, the only nominally Jewish Tina and Queenie Goldstein of the Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them franchise, who somehow manage to be Jews in New York in the ’20s while seeming very much like gentiles in New York in the ’20s. I’m not even referring to the troublingly semitic goblins who run Gringotts Wizarding Bank.

No, I have in mind a more thoroughgoing and structural Jewishness.

Imagine for a moment that I say I belong to a group of different people, a close-knit society within the larger culture that quietly carries on an ancient tradition, transmitting it from generation to generation.

Am I a Jew or a wizard?

Imagine I say that when I came of age, I got a letter in the mail that told me I had been admitted to a special school for people like me, a school in which I could study the arcane traditions and practices of our people.

Am I talking about Hogwarts or Yeshiva University?

Maybe it was this similarity that first drew me to the idea of writing Jewish fantasy. After all, I am solidly of the Harry Potter generation; I was eleven, like Harry, when the first book was out, and his maturation paralleled my own. I was also a thoroughly Jewish kid. I was raised in Modern Orthodoxy, sipping folk magic with my kiddush grape juice. To me, Jewishness and fantasy didn’t seem like anything that had to be combined — they were already two sides of the same coin. Think of Singer, of Peretz, of An-sky, of Der Nister — the angels and demons, magicians and dybbuks in the rich literature of Ashkenazi Jews.

To me, Jewishness and fantasy didn’t seem like anything that had to be combined — they were already two sides of the same coin.

The only issue was that when I was a boy, I saw no work equally accessible to traditional Jewish audiences and lovers of contemporary fantasy — as Michael Weingrad would have it, no Jewish Narnia.

And so I set out to write it.

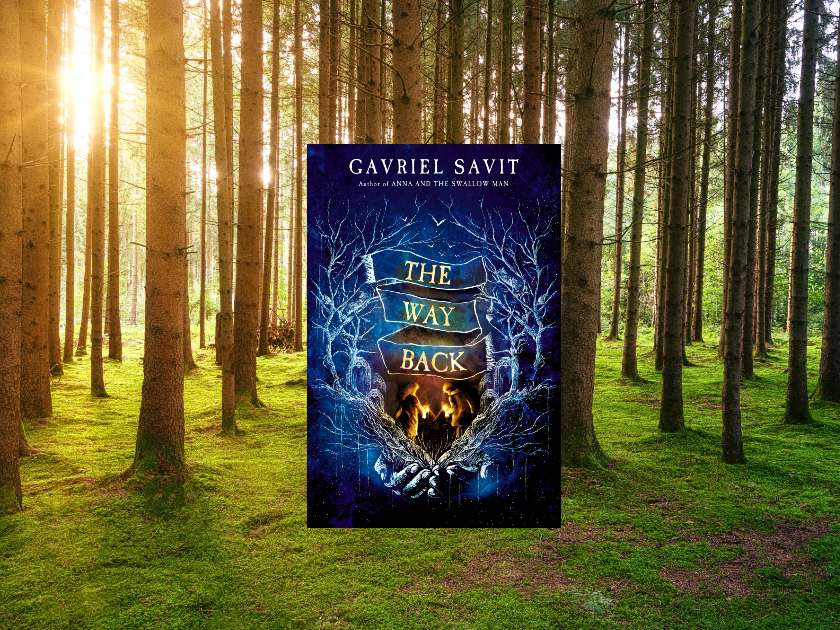

My new book, The Way Back, begins in a nineteenth-century shtetl of my own invention called Tupik. It traces the spooky adventures of two Jewish kids, Bluma and Yehuda Leib, as they struggle with and eventually declare war on the Angel of Death. Along the way, they find themselves running up against ancient Judaic demons — Lilith, Mammon, Dumah — coming face-to-face with exalted rebbes and their devoted Hasidim, and bargaining with an angelic guardian that they never even knew was there.

It’s a book for the Potterheads in central Nebraska and the Lower East Side immigrants of 120 years ago.

I wish I’d had it to read when I was young. And I hope you enjoy it.

____

[1] It is unfortunately necessary to articulate here that my love and appreciation for J.K. Rowling’s work in no way implies the endorsement of her distressing and repugnant transphobia; I choose to take solace in the knowledge that Hermione would assuredly disagree with her views, certainly firmly, and likely loudly.

Gavriel Savit holds a BFA in musical theater from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he grew up. As an actor and singer, Gavriel has performed in three continents, from New York to Brussels to Tokyo. He is also the author of Anna and the Swallow Man, which The New York Times called “a splendid debut.”