Science fiction combines well with Judaism — a religion that’s always been open to questioning, discovery, and flexibility. Many fans know about Wandering Stars, the first Jewish science fiction and fantasy anthology compiled by Jack Dann. Others may fondly recall Marge Piercy’s futuristic feminist golem parable He, She, and It or Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, a team-up planetary exploration with a Sephardic Jew. Fewer know about Asimov’s Pebble in the Sky, Harlan Ellison’s Golem100, Harry Harrison’s The Daleth Effect, Robert Silverberg’s Dying Inside, Jack Dann’s The Man Who Melted, and the long list of indirectly Jewish releases by Polish author Stanislaw Lem and the Russian Strugatsky Brothers.

There’s also a great deal of Israeli science fiction and fantasy (the anthology Zion’s Fiction offers an excellent sampler of top authors). Indeed, individual short stories are more common than novels and fantasy is much more common than science fiction (a wonderful master list of all of the above is available). Still, one can find time travel adventures, alt-histories, Jewish aliens, clones, and robots. With such a variety, I’ve chosen to focus on specifically recent science fiction novels — from space opera to near future dystopias — all of which explore how the Jewish people would change and be changed by new technology.

Robert Zubrin writes a satire akin to 1984 in The Holy Land: A Tale of a Universe Mad Enough to Be our Own. It depicts the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through a story in which aliens purchase land in Kennewick, Washington, which they consider their ancient homeland. They add technological wonders while living peacefully with the locals. Sensing an opportunity, corrupt warmongers in the American government send in inadequately armed American troops to be slaughtered and radicalize their children to become suicide bombers. This work of speculative fiction brilliantly illuminates the situation in the Middle East.

Daniel M. Kimmel’s Father of the Bride of Frankensteinhilariously combines the two titular tropes to analyze contemporary culture. Phil Levin, harried Jewish father,narrates his daughter falling in love with a Frankenstein creation, (named Frank) who decides to convert to Judaism. Amid prejudice from many sources, their rabbi busily addresses issues about Frank’s body parts’ past as well as the concept of his soul — whether he has one and whether (with Frank’s delightfully self-deprecating humor) it’s Jewish. In a twist recognizable to many readers, it’s the secular parents who have never heard of many Jewish customs as they try supporting their daughter through her journey. It’s a light, fun romp that’s very relatable.

The Unincorporated Series follows the ancient Jewish community of Aish HaTorah, spread across five asteroids, asa revolution unfolds in the Kollin Brothers’ space opera. In book three, The Unincorporated Woman, one of the few surviving rabbis, Gedalia Wildman, calls on the Jews to evacuate in a great diaspora, following the rabbi like Moses to a new home. Discussions on conversion and circumcision by nanobot add in a recognizable Jewish element but also brings these stories into the future.

Joel Rosenberg’s The Metzada Mercenary Corps series tells the story of “space Jews.” Metzada is an inhospitable planet whose inhabitants are descended from Israeli refugees. Instead of becoming the traders and loremasters seen in Asimov’s Foundation and many other series, they become highly sought-after warriors. The heroes, mercenaries with a shining reputation, fight to keep their colony safe in a strong metaphor for modern Israel. They also keep kosher and obey Talmudic law. Like the Kollin books, this space opera seems designed for Jewish SF fans in particular.

Israeli author Lavie Tidhar wrote the short story cycle Central Station about his space port near Tel Aviv. They are a polyglot community of humans, cyborgs, and discarded robots who mostly get along with each other and advances in technology. Through it all, Boris Aharon Chong, an Israeli born from many cultures much like the station, struggles with bearing the weight of all his family’s memories. This works as a metaphor for trauma from the Holocaust, war, and other acts of violence.

Mary Robinette Kowal’s Lady Astronaut series won a Hugo Award. A planetary disaster motivates earth’s space program to launch a generation earlier, so female computers are recruited, including Elma York. She’s kosher and keeps Shabbat, and later holds a Passover seder on the way to Mars. The book emphasizes intersectionality as Elma learns to listen to Black astronauts and teaches young people that space and science are for everyone. It’s a sweet, heartwarming adventure trilogy.

Jewish Teen Dystopia Novels

Teen dystopian novels come in many variations. Some take place on a near-future earth, one in which an oppressive government enforces brutal laws until teen heroes topple the system. Others take place on alien worlds or colony ships. In the last few years, young adult publishers have been emphasizing diversity and also intersectionality.

Alex London’s Proxy follows rich kids committing crimes that condemn their proxy – an eighteen-year indentured servant – to punishment in their place. As the society riffs on the biblical concept of the scapegoat, Sydney Carton is mentored by Mr. Baram, an older Jewish man who tells Sydney of his great bible-inspired destiny. In fact, Sydney’s birth name is Yovel (Jubilee), a word that references freeing the slaves. The pair struggle toward freedom.

The Cureby Sonia Levitin has pairs of twins growing up in a dystopian future in which love, song, dance, and emotion are all taboo. The hero, Gemm 16884, is sentenced to death for his obsession with these forbidden feelings. Their only chance at survival is to take a mental trip to a moment of history that can teach him to change. On this mission, Gemm is a sixteen-year-old Jew in Strasbourg, 1348, a story that ends in brutal tragedy, though with a trace of hope for the future.

Sarah Pinsker’s A Song for a New Day spent 2020 described as one of the most prophetic science fiction novels: it describes a 2020 plague shutting down American life. Young people grow up only hugging their families, never attending theaters and large gatherings, and creating large online communities controlled by the megacorporations. Still, Luce Cannon defies the new assembly laws to give small concerts in person. As the story gradually reveals, she was born Chava Leah Kanner in a strict Hasidic community where she was forbidden to sing and play or fall in love with women. As she battles to express herself, a particularly touching moment at the High Holiday ceremony of tashlich leads her to healing and a moment of epiphany.

In Phoebe North’s Starglass, a ship of entirely Jewish passengers seeks a homeland in space. Onboard, everyone is committed to a Jewish life; at the same time, many of the mitzvot have been twisted into darker forms. A revolution is brewing, with the young people struggling towards a better life in which they can return to spirituality.

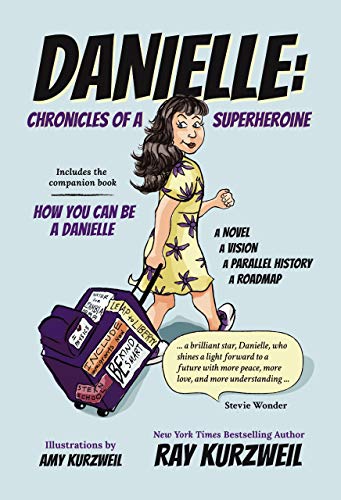

Danielle: Chronicles of a Superheroine by Ray Kurzweil follows a young Jewish prodigy as she transforms the current world. As the heroine makes a difference through small acts, her father reminds her of the Talmud’s words, that whoever saves a life has saved the whole world. She topples unjust governments, pacifies the Middle East, wins the Nobel Peace Prize, and jolts rabbis out of their fundamentalism in favor of helping others. The book ends with projects to help young people remake their own world.

Folklorist Valerie Estelle Frankel won an Indie Excellence Award and a USA Book News National Best Book Award for her Henry Potty parodies. She’s authored over 60 books on pop culture, analyzing Jewish science fiction superheroes, Star Wars, Harry Potter, Hamilton, Hunger Games, Doctor Who, Sherlock, and many more. She teaches at Mission College and San Jose City College. VEFrankel.com.