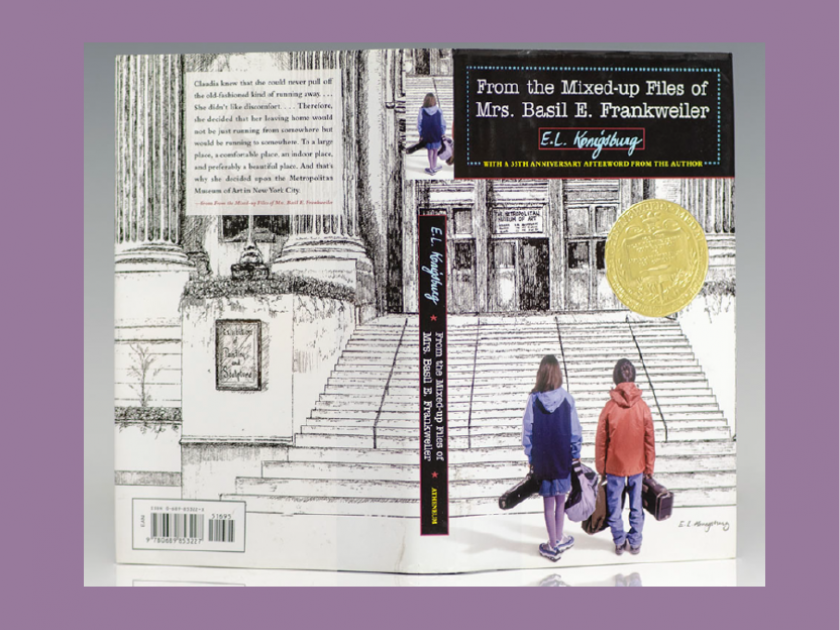

The novels of E.L. Konigsburg (1930−2013) have been critically praised for more than fifty years. Since the publication of the Newbery Award-winning From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler in 1967, countless young readers have identified with Claudia and Jamie Kincaid — two precocious and aggrieved suburban kids who escape the monotony of Greenwich, Connecticut, to hide in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Only one year later, Konigsburg delivered a very different group of characters in the overtly Jewish About the B’nai Bagels, the story of a Jewish-sponsored and coached sports league amidst complicated family relationships. Later in her prolific career, the author won her second Newbery Medal for The View from Saturday (1996), another thoughtful investigation of childhood, this one with both Jewish and non-Jewish characters, as well as ones whose backgrounds are of mixed ethnicity. What inspired Konigsburg to alternately ignore, express, and perhaps conceal Jewish identity in these three works about young people determining the truth of who they really are?

In her collections of essays and speeches for adults, TalkTalk, Konigsburg admits that “When I was a child, it would have been wonderful to read about a Jewish girl living in a small mill town with a father who worked long hours and a mother who ‘helped out in the store.’” She qualifies her statement with a virtual manifesto for a writer’s ability to embody different identities in her creations: “I am a Jewish-American female…But that is not all that I am. I am also overweight, prone to headaches, and a klutz…I am more than what I was, more than what I am, and part of the reason that I am is because I have learned to wear many masks.” Although the Kincaid family is not Jewish, to some extent Mixed-Up Files reveals the author’s conscious choice to both ignore her own background when writing the novel, and at the same time, to show some parts of it in her characters.

Most obviously, Claudia and Jamie are based partly on Konigsburg’s own children. She is the book’s author as well as illustrator; in an interview with Scholastic, she asserts that her children were the models for the book’s pictures and her daughter, Laurie Konigsburg Todd, has confirmed this key fact in a Smithsonian Magazine piece about the novel. Additionally, Konigsburg Todd directly attributes herself and her brothers as her mother’s inspiration for the novel. In 2013, Konigsburg Todd wrote in The Horn Book, “As she (her mother) listened to Paul, Ross, and me complain about insects and heat during a family picnic, she concluded that her suburban children would never run away from home by opting for a wilderness adventure. Instead, we would seek the comfort and splendor of the Metropolitan Museum.” It seems then, that Claudia and Jamie Kincaid represent one of the masks which Konigsburg claimed as an author’s prerogative in her ideal of literary creation. Although Claudia and Jamie started life as versions of the author’s own Jewish children, they assumed a different life in Mixed-Up Files.

In this book about the universal childhood experience of self-discovery, the question remains why the Konigsburg children became Kincaids instead of Kleins. Readers cannot know the answer to that question, although the mystery remains as intriguing as the contested identity of a statue in which Claudia is determined to unravel. There are traces in the book which may seem incidental, but are nonetheless invitations to consider Konigsburg’s decision to distance this book from her own life. For example, there is a surprising reference to Mrs. Kincaid’s membership in a Mah-Jong club, since that game was hardly a popular pastime for Connecticut WASPS in the nineteen-sixties. In fact, it was almost exclusively associated with Chinese and Jewish women.

In this book about the universal childhood experience of self-discovery, the question remains why the Konigsburg children became Kincaids instead of Kleins.

Surnames are another clue to the novel’s coded Jewish content. The author could easily have chosen unambiguously non-Jewish ones. Instead, both “Frankweiler” and “Saxonberg,” resonate with the same possibly Jewish origins as the name “Konigsburg” itself. The framing device of the novel is a letter which Mrs. Frankweiler sends to Saxonberg, her attorney, who ultimately is revealed as the children’s grandfather. His almost stereotypical indulgence of his grandchildren, and Mrs. Frankweiler’s sensible pragmatism, turn them into a complementary pair of Jewish grandparents, united in their concern for the children who need them.

The parents in About the B’nai Bagels also share concerns for their children, in this novel saturated with Jewishness — almost like Philip Roth for middle-grade readers. Yiddish-inflected language is woven throughout the story of a middle-class family living in a New York suburb. Mark and Spencer Setzer have modern American first names, but their last name is so Jewish it is “seltzer” with the letter “l” removed. Mark is twelve and about to become an adult by Jewish law, while Spencer is nine years older and commutes to N.Y.U from their home. Parents Bessie and Sam embody more old-world values, particularly Bessie, whose effusive guilt-inducing rhetoric is just short of parody. She frequently complains to God about the tribulations of being a mother, and her outbursts are somewhat justified. When her older son tries to psychoanalyze his mother’s refusal to add raisins to her stuffed cabbage as symbolic of her “resistance to change,” she fights back: “No one tells Heinz how to make ketchup, and no one tells Bessie Setzer how to stuff cabbage.” This is as far cry from Greenwich, Connecticut.

While the Jewish material seems comically exaggerated at some points, Konigsburg actually uses it as a background for a discussion of parenting, the difficulties of young adulthood, and the inequities of gender roles. Bessie takes on the job of managing Mark’s baseball team, sponsored by B’nai Birth. She partly uses this decision as a way to goad Spencer into coaching the players, but it is also clear that she enjoys exercising authority. Sam’s suggestions of how Bessie might alleviate her feelings of frustration with Spencer sting with sexism: “He advised her to wait a few months for this phase to pass, see a psychiatrist, or get some new interests.” Yet Konigsburg subverts the stereotype of an overweening Jewish mother who selfishly controls her children’s lives, while claiming to ignore her own needs. As the plot unfolds, it becomes clear that her apparent overinvolvement in her sons’ lives and the team is based on a true understanding of how children develop into strong and ethical adults. When her more polished and assimilated sister points out to her that the value of Little League is to teach the players how to accept both winning and losing “gracefully,” Bessie dismisses this notion with a more practical and insightful one, using Yiddish syntax: “Except how can a team learn to win and lose gracefully when all they do is lose?…I want they should feel rotten when they lose…Rotten but not hopeless.” With her expert narrative skills, Konigsburg also includes biblical references to the story of Jacob and Esau. When Bessie learns of how identical twin brothers on the team have exploited their respective left and right-handedness in order to cheat, her response is rooted in Jewish morality. Winning is far from the most important outcome and cheating will hurt the boys’ spirits much more.

Konigsburg includes in the plot an incident of antisemitism when Mark is called a “Jew Boy” by another player. Mark does not respond immediately, but almost rationalizes the attack: “That’s the way it is with kids like Botts. The feeling is always there. Like bacteria, just waiting for conditions to get dark enough to grow into a disease.” Both Konigsburg and her daughter had referred to antisemitism in their communities which made them feel marginalized and even led to physical attacks. Antisemitism is, of course, entirely absent from Mixed-Up Files, although the Konigsburgs’ town does have a brief cameo. When Claudia and Jamie check The New York Times for coverage of their disappearance, they miss an article about a pair of missing children from Greenwich, including the small detail that the search for them has widened to the neighboring communities of Darien and Port Chester. Konigsburg’s inclusion of this detail does not advance the narrative, but it allows her to include an autobiographical detail which becomes poignant in light of her children’s experience.

Tracing the different proportions of Jewish identity in her novels enriches our appreciation of this generous and insightful Jewish American writer.

If Mixed-Up Files contains no explicitly Jewish content and B’nai Bagels is one hundred percent aligned with Jewish identity, then the The View from Saturday includes a new perspective — that of children with one Jewish parent. By the time of its publication almost thirty years after the earlier books, a great deal about Jewish ethnicity had changed. Specifically, intermarriage had become much more common. The novel begins with a wedding in Century Village— a Florida retirement community— between two widowed people, one Jewish and one gentile. After the wedding, their grandchildren, Nadia Diamondstein and Ethan Potter, return to upstate New York, where they attend the same school and become members of the same Academic Bowl team. Noah Gershom, another team member, is also the grandson of Century Village residents. Although Noah observes that “almost everyone who lives there is retired from useful life,” and has acquired a new identity. His grandpa points out that rabbis are the exception. Their identity remains consistent after retirement, as is the case with Rabbi Friedman, who will perform the wedding ceremony of Izzy Diamondstein and Margaret Draper.

Unlike the characters in B’nai Bagels, who are as endogamous as Jewish tradition had required, several characters in Saturday are intermarried or the children of intermarriage. Nadia and Noah discuss Nadia’s Jewish and Protestant descent casually, indicating that this dual heritage has become normalized to a certain degree. At the same time, however, Noah elaborates how standards are different for Nadia’s grandparents. Rabbi Friedman will marry them, according to Noah’s understanding, because they are too old to reproduce, making their different backgrounds irrelevant.

Most of the language in A View from Saturday is crisp and contemporary, but Yiddish influence is present as an occasional reminder of a vanishing past. Grandpa Izzy affectionately calls his new, non-Jewish, love zaftig, and Noah’s grandmother, embarrassed at her husband’s reference to their lovemaking, admonishes him that it is a “shanda far di kinder” to talk about this subject in front of a child. But when the novel leaves Florida and moves to Epiphany, New York, the Jewish elements recede. (As with Konigsburg’s choice of names for characters, this city name is not accidental.) Away from her Jewish father and grandfather, Nadia needs to discover her own identity. Konigsburg comments with some irony on new sensitivities about diversity which were clearly not part of her own upbringing in a small Pennsylvania town with relatively few Jews. Discussing possible subjects for their Academic Bowl questions with their teacher, Mrs. Olinksi, the team members know they should be prepared to answer questions not only about the Old and New Testaments, but also the Koran, and the Hindu Upanishads.

Jewish identity shifted among the three novels, from a shadowy suggestion in Mixed-Up Files to an intensely defining presence in B’nai Bagels, and finally, in The View from Saturday, as a generation about to disappear. E.L. Konigsburg was always open about her Jewish background, weaving it in and out of her fictional worlds along with the many masks she chose to wear as an author. In About the B’nai Bagels, she created characters as wholly Jewish as herself, while in The View from Saturday she reflected, later in life, on the changing and ephemeral nature of Jewish identity. Even in From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, she alluded to her own Jewish family in the text. We cannot determine exactly why she decided which mask to wear in every book. After all, as the narrator of The View from Saturday reflects about Mrs. Olinski’s reasons for her choice of students, “She didn’t know that she didn’t know until she did know. Of course, that is true of most things.” Sam Setzer’s analysis of his wife, Bessie’s, character is also true of the writer who created her: “Whatever she does, she does with her whole heart and soul. And her heart is large, and I think that her soul is, too.” Tracing the different proportions of Jewish identity in her novels enriches our appreciation of this generous and insightful Jewish American writer.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.