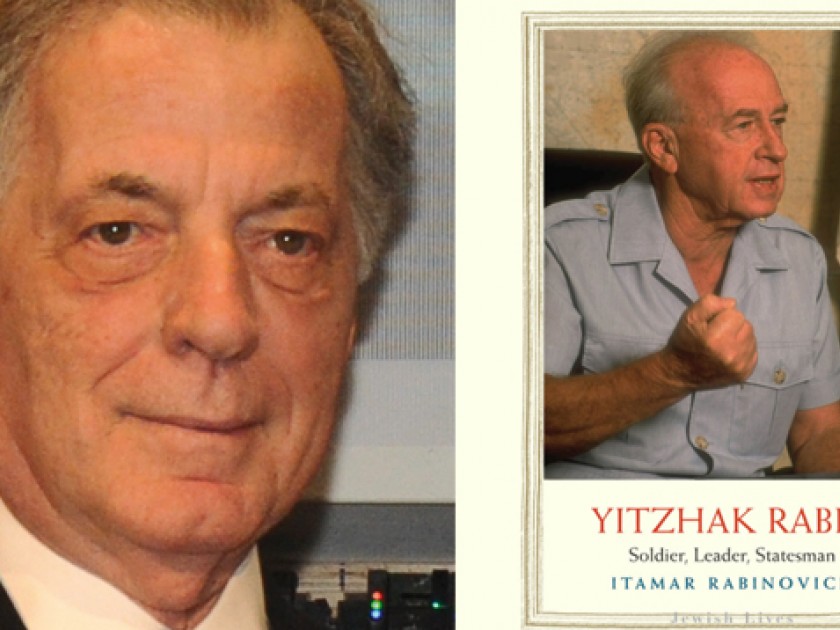

Itamar Rabinovich, former Israeli ambassador to the United States and president of Tel Aviv University, has written several books on Middle Eastern affairs and is most recently the author of Yitzhak Rabin: Soldier, Leader, Statesman, a volume in the Yale University Press series Jewish Lives. He talked with me about the book and Prime Minister Rabin.

Although he thought he knew Yitzhak Rabin well and worked closely with him, Professor Itamar Rabinovich says he learned much more about him while writing this biography. The most notable revelation was Rabin’s family background and the big influence his mother had on him. Rosa Cohen — Red Rosa as a left-wing radical in Russia — was a strong-minded intriguing woman who became a Labor Zionist in Tel Aviv. Rabin also had a certain sovereignty; if he believed in something, did it. He was anti-political parties, and it took him a long time to join one.

Another notable point was how early in Rabin’s career his talent for military affairs came through. Rabin had an intuitive grasp of military thinking and the ability to impart it. He was a good instructor — according to one student, the best military instructor he ever had, including those at the preeminent French École de guerre. Yigal Alon identified Rabin’s skills early on and elevated Rabin quickly.

The War of Independence in 1948 was a painful experience for Rabin. He lost half his men in the fighting on the road to Jerusalem. Leadership had not prepared for war. Rabinovich recalls an evening in Jerusalem when Bill Clinton and Rabin stood on a balcony overlooking the city and Rabin recounted the details of the failed attack to save the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem. Almost forty years later it was still in his mind. He remembered it vividly.

After the War of Independence, Rabin stayed in the IDF (Israeli Defense Force) despite its hostility to the Palmach (an elite fighting force in the prestate underground army), which Rabin had joined in 1941, and rose to the top of the military pyramid as chief of staff of the IDF. After the victory in the Six-Day War, Rabin was a major national figure and had to plan his next step. He had no interest in business and wanted to stay in public life; Rabinovich says the only way for him to be part of public policy was to move into politics. But he needed to hone his skills, and Washington was the place to do it. He asked Prime Minister Levi Eshkol for the ambassadorship to the United States, and Eshkol gave it to him.

In Washington, Rabin met Henry Kissinger, who in many respects became his mentor. He also had a good relationship with President Nixon. Despite what Americans may think of Nixon as president, Rabinovich notes that he was a great geopolitical thinker. He saw Israel through the lens of the Cold War and in a cold, calculated way considered Israel an asset. Rabin had treated Nixon well when he was a has-been, investing a whole day touring him in Israel, for which Nixon was grateful; the time spent laid the groundwork for their relationship. Rabin did the same for Jimmy Carter in 1973, when no one spent time with the governor of Georgia. But Rabin saw him as a stepping stone, although the time invested in Carter didn’t work out down the road. Rabin and Clinton clicked personally — a mutual love story — and had a close relationship. Clinton knew that what he saw with Rabin was what he would get; he knew where Rabin stood and what the situation was.

Rabinovich describes Rabin as a political dove and a military hawk. As early as 1963, Rabin had seen that Israel would not be able to keep up an arms race with the Arab and agreed to Israel’s nuclear project. But he saw the territory won in the Six-Day War as a bargaining chip to get recognition of Israel by the Arab states, not as an area for the settlers to move into, which Rabin strongly opposed. At this point the settlers were a minor movement that did not become a force until the mid-1970s. By the 1990s Rabin believed enough was enough. It was time to make peace. And it was a good moment — the United States was on an upswing after the defeat of Saddam Hussein, Russia was down after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Rabin recognized the moment and grasped it. The center left saw opportunities to use its bargaining chips.

Of the tracks to peace that had been opened, Rabin preferred to work with Syria, an immediate neighbor, to counter the greater danger he saw in Iraq. Rabinovich, as chief negotiator with Syria, was in the middle of these events. He says the advantage of being a diplomat after being a professor of history was that he had a critical sense of what was happening. In August 1993, as negotiations with Syria were to begin, Rabin deposited with the U.S. Secretary of State Warren Christopher an oral offer that Israel would leave the Golan, but during his negotiations Christopher was to keep to himself until Syria agreed to a set of conditions. Rabinovich remarked to Dennis Ross, his US counterpart, that he could hear the wings of history in the room. Looking back, he says all three parties — Hafez al-Asad, the president of Syria; Israel; and the United States — made mistakes. Christopher put the offer on the table; even if Asad had been interested in making peace, he began negotiating, according to Rabinovich, like the victor, not the vanquished. The opportunity was missed. With the track to Syria closed, the Oslo process, begun in 1992, was the only game in town.

When we spoke, Rabinovich had just finished reviewing the play Oslo. He sees it as good theater but not a good rendition of reality. It places too much emphasis on the people in the negotiating room and not enough on the leaders. Rabin agreed to Oslo only because the deposit in Syria failed.

Of the relationship between Rabin and Shimon Peres and their relationship with the Israeli public, Rabinovich observes that although Rabin had a blunt manner, the Israeli public saw this bluntness as a sense of his directness. He was someone who spoke candidly, and he built credibility and authority. This was what allowed him to come back in 1992. Peres was a very gifted man, but he had a credibility problem with the public. Peres and Rabin did not like one another, but they complemented one another and when they collaborated, they were very powerful. When he was ambassador to the United State under Rabin and Peres was foreign minister, Rabinovich was in the middle, between them, and saw both sides. He did not play games. He avoided the familiar technique of going around the foreign minister by sending telegrams directly to the prime minister. Peres knew who Rabinovich was and knew he was loyal to Rabin. They developed a good relationship that endured.

The year 1995 was a bad time. The Israeli mind set was that, if there was an assassination attempt, it would be by an Arab. Security was planned to protect the prime minister from Arabs, not Jews; Jews do not kill Jews. After the assassination, Israel copied the US security model.

In answer to whether it was hard to go back over this material, Professor Rabinovich said this is life, and life goes on. He was invited to be president of Tel Aviv University and after that has continued serving in academic and public life.

Prior to starting work with Rabin, Rabinovich had a superficial social friendship with him. During nearly four years of work with him, he was Rabinovich’s leader, and the two also developed a close personal relationship. Rabin was an introverted man, but once you gained his confidence, he became accessible. He demanded loyalty but also gave it. It was a pleasure to work for a leader who was wise, experienced, open, and trustworthy. A word was a word. You always knew where you stood, and you also knew that you were part of a great historical moment.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.