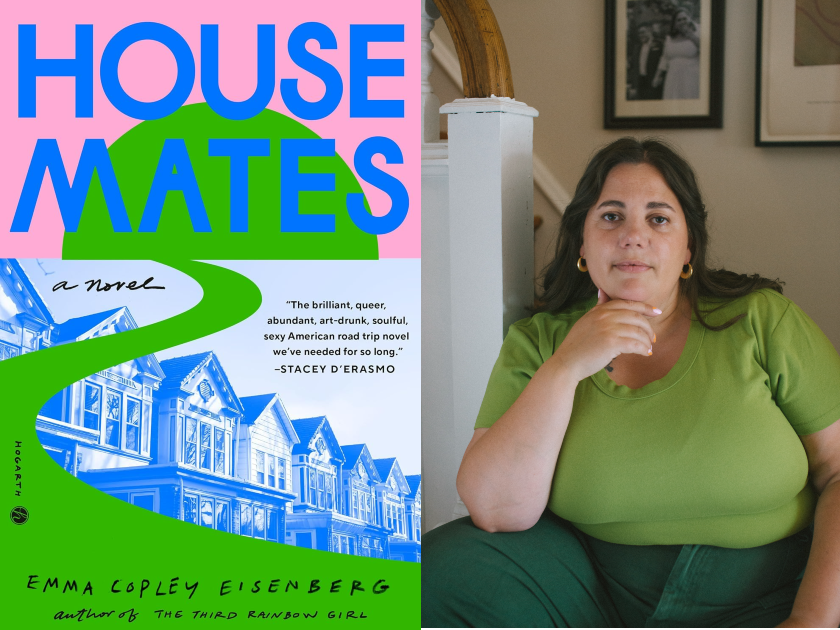

Author photo by Kenzi Crash

Chloe Cheimets speaks with Emma Copley Eisenberg about the big questions that informed her mesmerizing debut novel, Housemates. They discuss the dynamic between artists and collaborators who are in a romantic relationship, the queer scene in Philadelphia, and creating art in our contemporary times.

Chloe Cheimets: In 1939, photographer Berenice Abbott and writer Elizabeth McCausland published Changing New York, a landmark photo series. In your book Housemates, photographer Bernie Abbott and writer Leah McCausland develop Changing Pennsylvania, their own multimedia collaborative art project. This book is in conversation with historical figures without being explicitly about them. What drew you to this kind of project? In what ways are your characters similar to their antecedents, and in what ways do they diverge?

Emma Copley Eisenberg: It’s true! I came across a biography of Berenice Abbott in 2017 at the exact moment in time when I was asking all these big questions, Sheila Heti-like, “how should a person be?” It felt like being an artist and being a queer person in America were impossible, and it felt like finding love and being truly together with someone was impossible. In the biography, I learned that Abbott was this raw, ambitious, talented lesbian photographer who went on a real road trip with her crush – an art critic named Elizabeth McCausland – and they came back as life partners and creative partners, ready to embark on a city-defining collaboration. That road trip (what happened on it?) birthed my novel. I wanted to take the idea of a car journey being the site of life-changing intimacy and artistic inspiration but make it fundamentally about the challenges facing queer artists today. Many of the places that Bernie and Leah go in Housemates are actual places that Abbott and McCausland went, but many of the fictional stops diverge from the real ones too. Very little else of Abbott and McCausland’s real lives made it into Housemates but a great deal of the book found its origin in them. McCausland was tall and fat and butch. Abbott had a mentor, the French photographer Eugene Atget, who taught her how to see and whose artistic legacy she took up and carried with her for the rest of her life. McCausland had a girlfriend whom she tossed aside for Abbott; Abbott had a big heartbreak with a womanizing princess before she met McCausland. Everything else I made up!

CC: Housemates has a nested structure. There’s the central story of Bernie and Leah, queer artists, housemates, and collaborators. And then there’s a frame story that echoes the central story –another queer artist, unnamed, at least a generation older, who also collaborated with her lover, watches Leah and Bernie and narrates their lives as well as her own. How did you land on this narrative voice? What does she add to the text?

ECE: I didn’t set out to write a nested structure; I’m but a simple girl that usually likes pretty simple stories of characters who just open their mouth and narrate. But I’m a huge believer in the idea that craft innovations usually come to be because of problems you’re having in the writing. I kept writing the point of view of this novel in different ways, and it always felt like it wasn’t quite working, wasn’t quite directing the reader’s attention to what I wanted the book to be most about. More than being a love story or a road trip story or a story about Trump’s America in 2018, I most wanted this book to be about artmaking – the cost of it, what it can and can’t do, and how it is actually done. So I kept trying to solve the point of view problem and then one day the first person point of view just sort of appeared, fully formed, talking to me. I had a choice – shut it out (who was that voice? I’m almost done with this book!) or let it keep talking. I decided to listen. And I’m glad I did, even though the “I” makes this book a little less simple, I think it gives the book a second layer of knowledge, of generational queer differences, and of time passing. The older narrator is trying to figure something out for herself – can art really save your life? – by watching and learning from a younger generation of queer artists.

CC: Bernie and Leah have a complicated relationship. They are collaborators and lovers, not quite friends. There’s an imbalance between them — Bernie is more artistically recognized and more beloved. Could you speak a bit about this creative and romantic partnership? How central was this imbalance to the story you wanted to tell?

ECE: It was really central. I’ve always been really interested in Carson McCullers’ idea that in any romantic relationship there is always “the lover” and “the beloved.” I got to thinking about how that dynamic would shift if two people in love are also making art together. The world often intercedes and decides which person in a duo is cooler, more important, the main character of the sexier story, regardless of how true that story really is. In real life, McCausland never really quite got her due; Berenice Abbott outlived her and outshone her in the historical record. In Housemates, I wanted to conjure this imbalance but also undermine it, and think about the ways that the less “shiny” partner in a twosome is sometimes the most important, even foundational presence. Bernie sees some things that Leah doesn’t, but Leah sees a lot of things that Bernie doesn’t too – like how to articulate their joint project, how to love, how to be a part of a community, and how to stay the course of togetherness over the long haul, qualities that are traditionally undervalued in an artist.

CC: This novel reads like a love letter to the queer scene in Philadelphia. What role does this community play in your writing practice?

ECE: I do think of this book as a love letter to queer community, for sure, and a love letter to Philadelphia, a major and majorly gorgeous east coast city that is severely underseen in literary fiction. I’ve lived in Philadelphia almost my whole adult life now and so my neighborhood of West Philadelphia, which is very queer and has a very tight knit almost shtetl-like atmosphere, has become the site of all my becomings and mistakes and important moments. I have so much respect for this community, for the ways that it holds itself to a high ethical standard of behavior and imagines a more just world. I also poke gentle fun in the novel at the ways that my particular queer neighborhood can become prescriptive and judgemental, often, I think, as a response to feelings of guilt and shame about gentrifying a historically Black area. All of these elements mix and show up in my writing. This community shaped the final project that Bernie and Leah create in the novel, and it inspires me and offers me logistical support in ways that are essential to my ability to keep writing.

Everything old is new again; we’re hungry, I think, for slowness, and for detail and nuance in our images.

CC: Pennsylvania, in all its contradictions, plays a central role in this book. There’s so much geographic and sociological detail here about a deceptively huge state. Tell us about the research process for a text with so much detailed setting.

ECE: At a certain point, I realized that though I lived in Philadelphia, I knew relatively little about the rest of the state, which is so varied, and includes Steelers country, Pennsyltucky, coal country, almost-Canada, and the Poconos, among other areas. I began to take day and overnight trips to different parts of the state, seeing natural caves, Amish country, post-industrial manufacturing towns, dramatic mountains, and more. I began to learn about events that put Pennsylvania on the national stage, like Flight 93, the plane that went down in a reclaimed coal mine on 9/11, and to study Philadelphia’s decisive role in the 2020 election. I read Galway Kinnell poems and think pieces, but mostly I just drove myself around and did what Leah and Bernie do – talk to people. I still consider myself a beginner when it comes to Pennsylvania.

CC: Bernie is a large-format photographer. According to this book, it’s a painstaking, but magical medium. What drew you to write about photography? As an art form, how do you think it complements text?

ECE: In another life I would have loved to be a photographer; I’ve always wandered to the photography wing in any museum. My dad always questioned whether photography was as much of a “real” art form as painting, say, and I always maintained that it was. The real Berenice Abbott with her big heavy camera was the starting point and it didn’t take long for me to learn that large format is still an art that is practiced today. I was attracted to the ways it has historically been coded as a tool only used by “the masters,” usually men, and how fussy and difficult it is. I am someone who is always attracted to hard things, and I think Bernie is too. While I was writing the book, there was also some synchronicity going on because all these articles began to come out about how Gen Z is casting their phones aside in favor of returning to film photography. Everything old is new again; we’re hungry, I think, for slowness, and for detail and nuance in our images. I was also really fascinated by the idea that a large format camera’s eye can actually “see” more than a human eye. If that’s not a metaphor for the novel itself, I don’t know what is.

CC: This book confronts a lot of recent American history. We encounter so many events of the last decade – the Trump presidency, Black Lives Matter protests, COVID. What about this period did you want to capture?

ECE: I wanted to set the book in 2018, in the middle of the Trump years, as a record of that time when we were halfway in, when many of us felt that all the systems we were accustomed to relying on were crumbling, but hadn’t yet fully decompensated. We didn’t yet know how much worse things were going to get; in some ways, that year was the last gasp of the old way of thinking about America, maybe. I was interested in those big Events you mention, but maybe even more, I was interested in how those big Events were talked about, made into information or stories or news which then became narratives that filtered down into our lives. I had a lot of fun bringing that aspect onto the page by playing with headlines that are part real and part fake, and writing fake obituaries and parodying the reverent and withholding tone of centrist publications like The New York Times and the Associated Press.

CC: What are you reading and writing right now?

ECE: I’m very excited that my next book, a short story collection called Fat Swim, will be out next year. I’m having a ball going back into a few of the stories to tighten and deepen as well as writing two brand new stories. I love stories! They are maybe my favorite form, certainly my home base and first love form. Reading wise, I’m really looking for funny right now, and I’m really looking for real feeling, big feeling, books that swing for the fences emotions-wise rather than hedging their bets with irony and meanness and disaffection. Recently in this vein, I really loved Brother and Sister Enter the Forest by Richard Mirabella and We Do What We Do in the Dark by Michelle Hart.

Chloe Cheimets has an MFA in fiction from The New School.