Jewish Book Council had the pleasure of featuring Miriam Libicki as part of Ink Bleeds History: Reclaiming and Redrawing the Jewish Image, a panel of graphic stories on the representation of Jews in comics and graphic novels. We followed up with Miriam to discuss her collection of drawn essays, Toward a Hot Jew.

Michelle Zaurov: I notice you talk a lot about graphic artists who are Jewish. Do you feel like being Jewish has had any influence on your relationship with comics or being a comic artist?

Miriam Libicki: We read Marvel comics when I was young, but I think it was Peter David who put a lot of Jewish content in in his ‘80s comics and I was aware pretty early on that comics were a Jewish medium. I grew up Modern Orthodox, so it wasn’t super strict, but I felt like in my schooling and community there was a sense that visual art wasn’t really a thing that Jews do. The notion was that it’s nice for kids to have coloring books, but art is not a serious or intellectual pursuit. I was into fine arts and history of Western art, and that didn’t feel very Jewish to me, whereas comic art managed to feel Jewish somehow and have some Jewish sensibility to it.

MZ: These essays seem to be on disparate topics: you have one about art and another about Jewish identity. Did you mean for them to all go into a cohesive graphic novel?

ML: Well, I did them all separately. It was 10 years’ worth of essays, so I did them all as self-published zines. I was doing comics and going to comic cons, I had an ongoing series, jobnik!, which is about my time in the Israeli army, that morphed into a graphic novel. Whenever I had some rant or thought that I wanted to put in comic form, I would put out one of these drawn essays and sell it at a convention. Once I had two or three of them, I decided that once I had enough of these graphic essays, I would submit the full collection to publishers.

MZ: Why did you decide on these subjects?

ML: It just seems to be what I care about. I didn’t really intend to focus on Jewish subjects, and I think it was a reaction to leaving Israel and coming to Vancouver. I felt that Vancouver was not really a Jewish place after being in Israel, and I was afraid of becoming just another white person. People wouldn’t even perceive me as Jewish, and somehow that bothered me. So, my art at that time started becoming more Jewish. I found myself making excuses to have Jewish themes in my art as a way of asserting my identity that felt comfortable to me. This seemed like an authentic way to express and explore my Judaism on my own, when I didn’t have my community or my whole country reinforcing it.

MZ: How did you feel when you returned to Israel and interviewed actual Israeli citizens after being away?

ML: It was very different. I was grappling with my identity because I had made aliyah, served in the Israeli army, and the idea was to become a real Israeli and not an American tourist, and somehow earn my place in Israeli society. But I moved to Canada right after the army. So, I undermined that whole project and I felt very ambivalent about it for a long time. I still wondered how I could be a part of the Israeli conversation, and that is what the early essays were about: if I can understand the Israeli mindset, then maybe I am still partially Israeli. But, each time I go back, I get more rooted in Canada. I got married, had Canadian kids, and now when I travel with my family to Israel, I won’t even speak Hebrew most of the time. I really feel like a tourist with pretty good Hebrew. And I guess that’s ok. Now I am more interested in defining my Judaism as a Diaspora sort of Judaism rather than an Israeli one. I stopped struggling with it; I don’t feel the need to prove myself as an Israeli anymore.

MZ: On a more general note, what was the most difficult part of the artistic process with this novel?

ML: The part that takes longest is always the art. In order for me to do the art, I need something to keep me going, like a strong story that can sustain all these hours working on art. It’s difficult in the beginning to figure out what I’m writing and why I am writing it. Once I get over that, the rest comes pretty quickly, but the art is still long because I don’t draw or paint fast.

MZ: I noticed that some of your essays lack in color while others are colorful, is there a tactful reason for that?

ML: It was more practical. “Towards a Hot Jew” was meant to be a drawn essay, and it was a breakthrough in what I wanted to do in comics. It’s in black-and-white because I didn’t want to make it more complicated, and it was more about the writing and the ideas rather than the art. I felt like if I added color, I would have worried about the realism of the art. The other ones atr in watercolor because I wanted to teach myself watercolor, and the “Jewish Memoir” was commissioned for an academic anthology publication, and I couldn’t put that in color for cost reasons. The final essay is in a limited orange palette, and that was kind of for the same reason. When I was still two-thirds of the way through the art, I didn’t have a publisher for it, but the idea was that I wanted to get it published in an academic context, like a journal or an anthology. I also knew that this was the essay that would put me over the top for the essay collection in terms of page count.

MZ: In the book, you say that “comic style editorializes human appearance” and “fictionalizes it in order to bring certain aspects of humanity to light.” How have you done that with some of the characters you drew up in this book, and what aspects of humanity did you hope to bring to light?

ML: My avatar in the essays is based on the character that I drew for jobnik!. I kept drawing that character until one felt right to me. Her looks did undergo a transformation over the course of the first few issues and stories I wrote about my army experience. I gave her bigger eyes than mine, but she certainly isn’t glamorous. She’s shorter than me, which is kind of how I feel. Sometimes I feel more slight and observant, and not physically dominating.

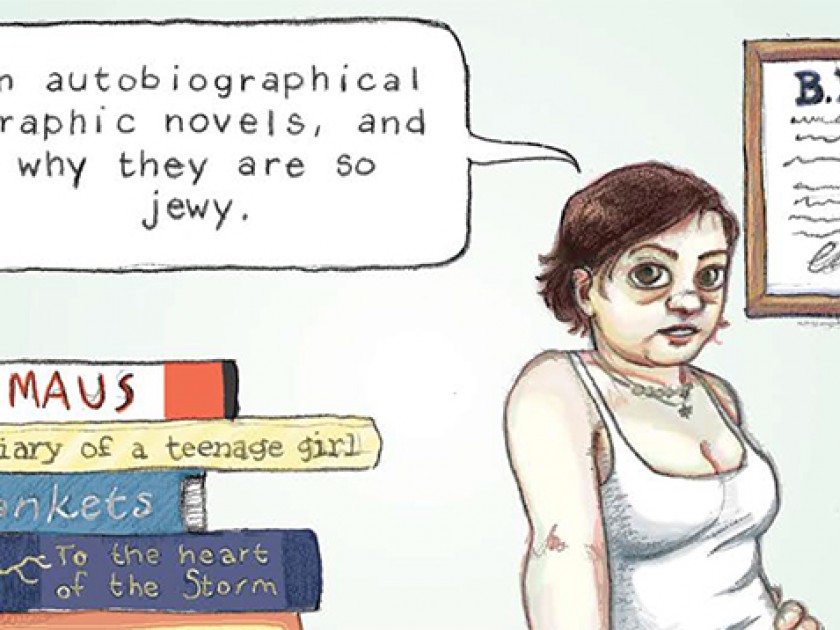

The eyes are emphasized but the rest of the face is fleshy as well because in my late teens and early twenties I didn’t like my appearance very much. It’s not that she’s hideous; the point that she’s just not glamorous and put together, and her body is sort of lumpy. After that, I didn’t pay attention to how much she looked like me. When I did the essay “Jewish Memoir Goes Pow! Zap! Oy!,” it was the first time I had that character addressing the reader and expressing thoughts on literary criticism. I picked the appearance of what I was redrawing at the time of the jobnik! stories, which was the Miriam character with the short bob cut and casually half out of the army uniform. That suited the tone I was going for with writing the essay about memoirs — it was in the authority of lecturing but in the form of someone human and vulnerable. She not only has a body, but a flawed body, and even when I’m talking about the history of race relations it’s still coming from a human.

MZ: In the “Towards a Hot Jew” essay, you touch upon the sexual stereotypes of Jewish men and women. Do you feel like Jewish stereotypes, specifically of young Israeli soldiers, differ from those of the average young Jew?

ML: Definitely! I feel like there’s a whole thing about soldiers who were the guards in the Ben Yehuda Pedestrian Mall in Jerusalem: those are the soldiers who would get all the action. Now, for the past 15 years, it’s been the armed escort on a Birthright tour. Everyone wants to have their “sex with an Israeli soldier” experience. Among Israelis, soldiers aren’t necessarily seen as sexy, but they know that they’re perceived as such in the rest of the world. I feel like Israelis have caught on that their sex appeal is one of their selling traits, and there’s definitely more of an internal fetish as well. Which is a little bit disturbing because it’s one thing when outsiders think Israelis are sexy and it’s quite another when official branches of the Israeli government are putting up sexy soldier pictures.

MZ: You also talk about how there’s an imperfection that goes with Jewish culture. Do you feel like that plays a role in the sexuality of Jews?

ML: I think so. I feel like sexuality influenced by Christian doctrine, you get the Madonna-whore complex: either the woman is ideal or totally dirty. I would hope that in Judaism, especially since we don’t have a Madonna, that we would have less of that, that someone could be human and still be desirable. Maybe we can avoid putting each other on pedestals; maybe we can acknowledge that we are all not perfect and that we all have big noses and are sexy anyways.

MZ: In one of your essays, you say that “psychoanalysis is a quintessential Jewish pursuit.” What do you mean by that?

ML: A lot of people have made the point that Freud’s middle-class Jewish upbringing was why he had his specific thoughts on familial relationships, that if it weren’t for the very specific German-Jewish family structure Freud grew up with, he wouldn’t have had all those theories about what parents and children relationships are. I definitely feel like psychoanalysis caught on among Jewish people earlier than it did with the mainstream, who were initially largely anti-psychoanalysis or found it disgusting that people went to talk to psychoanalysts about their private life — which is reminiscent of the way they found Jews to be dirty and disgusting. It’s a Jewish thing to believe that you should talk about yourself and acknowledge your flaws, and that talking or complaining about a subject endlessly is a method of taking action to solve problems.

MZ: Do you feel like these Jewish stereotypes were fading when you moved to Canada?

ML: I think people on the West Coast and in Canada had less of these stereotypes than what you might find on the East Coast and the United States. A lot of people aren’t familiar with the Jewish stereotypes out here, let alone Jews. In “Towards a Hot Jew,” I talked about the concept of the Jewish American Princess (“JAP”) being shallow and materialistic. I was doing that project in Canada that asked non-Jewish Canadians if they had a version of the JAP, like a Jewish Canadian Princess, and they uniformly claimed that there isn’t. So I would say there’s a little bit less awareness.

MZ: In the later essays, you were pointing out the downfalls of the Israeli government, like how they have alienated Ethiopian Jews and the Sudanese throughout history.

As an Israeli citizen, do you feel a personal guilt on behalf of the government? Or do you feel like you removed yourself from that because you moved away?

ML: I have that guilt, but it’s not huge. Even if I tried to make things different I can’t have that much of an effect: there is no absentee voting in Israel, so I can’t vote unless I made a date to be in Israel on Election Day. I could have more of an influence, but I feel like I can’t be that much of an activist outside of Israel. I do tweet and say “Shame on Netanyahu!” but I feel like there is a real sense in Israel that the rest of the world can’t judge them. The American Jewish community does have a place in talking about Israeli policies, but insofar as to actually effect what happens inside Israel, I’m not sure I can have that much effect as an American/Canadian.

MZ: Why did you decide to end the book on the quote “How can we deliver a message about our humanity from behind the bars of quotation marks?” What does this mean?

ML: That is a quote from the Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. He was a World War II refugee who survived a prisoner of war camp, and a philosopher before and after the war. His core idea is empathy, and he was one of the people to really try to define it. He was also an Orthodox Jew and talks about it in spiritual terms, like the image of God. He talks about the need to look beyond categories — when he thinks about categories he thinks of the Germans walking outside of his camp who presumed they were a different kind of humanity than he was. If you have those categories then there’s no way you’ll be able to communicate, and everything you say will just become a symbol of how that person has already defined you. In the essay I was grappling with the ideas of identity politics, that you need to have identity politics because otherwise you have identities and categories and hierarchies that are left unspoken. It’s better to have them spoken, but it’s also important not to retreat so far into them that the only thing you can express is the identity you have been sorted into. It’s important to examine structures and hierarchies but it’s also important to take those and put them in their place and try to see the infinite in all of us, as well.

MZ: Identity and categories and how they shouldn’t be at the forefront of society seems to be a huge emphasis in your essays. Were you raised with this notion?

ML: I think so. My parents were Orthodox, however neither of them grew up Orthodox. My mother was a convert and my dad was more Conservative-Reform. Their attitudes towards Orthodoxy was more about how they chose to live their life and acknowledging that everyone has their own paths in life. They gave me spirituality and tradition but their moral sense was much more universal. I feel like I have the ideas of universal morality and empathy. We all believe there are many paths to the truth and ways to be a good person.

MZ: What are you working on now?

ML: I’m working on a bunch of projects right now. I just worked with the original underground comic artist and comic feminist historian, Trina Robbins. She is putting out a collection of fiction by her father that was published originally in Yiddish, which she found, translated, and adapted as a comic script, which she gave it to different artists to draw. I’m also working on another short piece about graphic ‑novel responses to the Holocaust. It is closer to fiction than non-fiction, so it’s more of a narrative than an essay. I’m also doing my Masters right now and working on my thesis, which is also a graphic novel.

Michelle Zaurov is Jewish Book Council’s program associate. She graduated from Binghamton University in New York, where she studied English and literature. She has worked as a journalist writing for the Home Reporter, a local Brooklyn publication. She enjoys reading realistic fiction and fantasy novels, especially with a strong female lead.