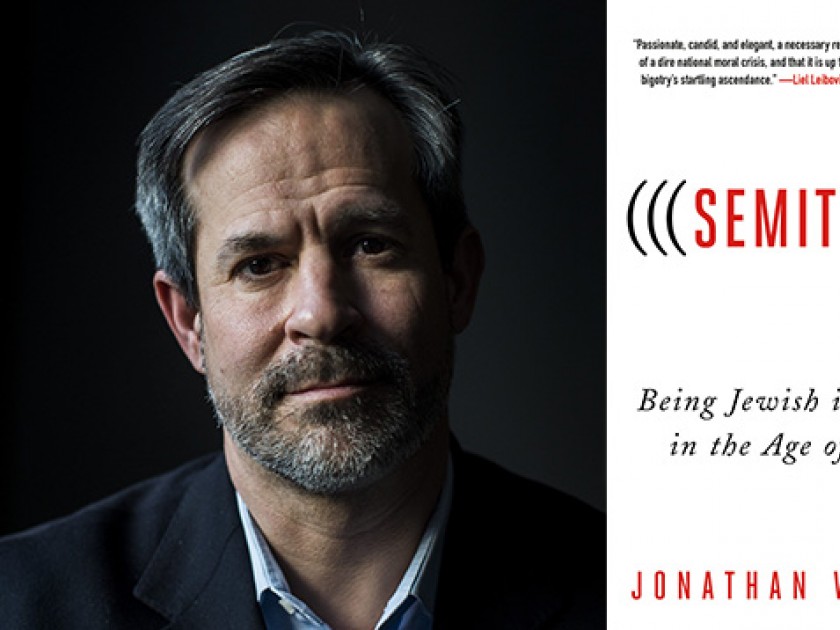

In (((Semitism))): Being Jewish in America in the Age of Trump, Jonathan Weisman explores the disconnect between his own sense of Jewish identity and the expectations of his detractors and supporters. He delves into the rise of the alt-right, their roots in older anti-Semitic organizations, the odd ancientness of their grievances―cloaked as they are in contemporary, techy hipsterism―and their aims―to spread hate in a palatable way through a political structure that has so suddenly become tolerant of their views.

Michael Dobkowski: In many ways your book is about Jewish identity and experience in the Trump era. How has the American Jewish experience changed―generally, and for you, personally?

Jonathan Weisman: I grew up in a very Reform household. Although I was raised to identify as Jewish, I — like many Jews of my generation — drifted away, in part because Jews had become entirely comfortable in a pluralistic, liberal democracy that seemed to be progressing inexorably toward tolerance and acceptance. I thought of anti-Semitism as an issue of the past. Then came the Trump campaign and the emergence of swarms of white nationalists who pressed for Mr. Trump’s election. I became a target of the alt-right’s attack, forcing me to reconsider my identity in light of how the bigots were identifying me.I could embrace Judaism as a system of beliefs, a culture, and a religion or I could shun it. But I could no longer ignore it. And so I embraced my Judaism. I fear that too many Jews have rationalized away the threat of white nationalist hate to justify political and social views that were formed before the emergence of this changed reality.

MD: Do you think these changes are temporary and reversible or have we reached a tipping point?

JW: It is difficult to know whether we are living in a temporary era of intolerance that will be seen as a brief interruption in the post-World War II progression toward pluralism and democracy — or whether that post-war progression was, in fact, the historical aberration. It is not just the rise of hate and intolerance. Democracies and fledgling democracies like Hungary and Russia have slipped back into crony authoritarianism. Intolerant nationalism is rising around the world. I still have faith that Americans love our institutions and traditions, and that we can save what makes us Americans. But I am less sure by the day.

MD: Much has been written about the so-called “new anti-Semitism.” Do you think the threats posed by the alt-right and their allies are fundamentally different from earlier expressions and manifestations of American anti-Semitism?

JW: The alt-right’s anti-Semitic beliefs and tropes are oddly anachronistic. They are precisely the aspersions that I learned about as a child in Sunday school: Jews are both rapacious, greedy capitalists and dangerous, left wing anarchists; they are at once all-powerful puppet masters and sniveling weaklings; they control the media and through it, they have corrupted popular culture with their decadence — yet they are forever foreigners, never truly Americans, never truly part of American culture. It makes no sense, but those contradictions have shown remarkable staying power, and in that sense, the “new anti-Semitism” is centuries old. What distinguishes the alt-right from its predecessors is its method of organization, its technological savvy, its sarcasm and irony, and its ability to at least seem ubiquitous. By spreading its ideology on Twitter, Reddit, YouTube comment sections, 4Chan and 8Chan, the alt-right has become unavoidable for my children’s generation. It is not an invisible subculture, talking to itself on its own websites, segregated from the wider World Wide Web. The alt-right is disseminating its ideology. Most young people reject it, but there will always be disaffected searchers who will be drawn to the sophistry of hate.

MD: Are racism and anti-Semitism becoming normalized in certain segments of American society — and if so, what does it mean to normalize these social pathologies?

JW: Racism and anti-Semitism have always been normal in certain segments of American society. But when the president of the United States says “very fine people” marched in Charlottesville on both sides, has so much difficulty condemning the bigots who love him, and presses policies that are seen by racists and anti-Semites as dog whistles that ratify their beliefs, we are all at risk. Expressions of intolerance are no doubt more tolerated now than they were two years ago. We are learning that pluralism and diversity are not as valued as we once thought.

MD: You are not afraid in this book to talk about things that happened to you, your family, and other Jewish journalists. Why do you feel it is so important to tell this story?

JW: I wanted this book to be personal, to not be abstract or theoretical. And I believe that my background — a not-particularly observant Jew who struggled through a mixed marriage and tried, not very well, to impart a Jewish identity to my children — would be recognizable to a lot of Jews of my generation and younger, and to non-Jews who wrestle with their own identities in an atomized society. For someone so assimilated as myself to be singled out and attacked by anti-Semites should have resonance beyond observant communities, but that resonance would emerge only if I was willing to delve into the personal.

MD: Who are some of the writers and scholars who helped you understand the state of American society today? The state of American Jewish society?

JW: I read Bernard-Henri Lévy, Hannah Arendt, Timothy Snyder, and Melissa Fay Greene, but this book was shaped more by the rabbis, activists, and victims I spoke to: Rabbi Francine Roston and Tanya Gersh in Whitefish, Montana, who suffered through anti-Semitic attacks far, far worse than anything I saw; Rabbi Daniel Zemel of Temple Micah in Washington, who taught me to apply Jewish law to shape a response to bigotry; Rabbis Jonah Pesner and David Saperstein of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, who helped me put the current moment into modern history; Ken Stern of the Justus and Karin Rosenberg Foundation who was frank and honest about his time at the American Jewish Committee; and Zoe Quinn, who showed me the technological roots of the alt-right and the nuts and bolts of a technological response.

MD: Since you finished writing the book, are there any developments that would lead you to modify your argument, or even strengthen it?

JW: I had just about finished this book when Charlottesville, Virginia erupted in chants of “Jews will not replace us” and bigoted violence, and the Internet hordes of the alt-right jumped into visceral reality. I was able to lace the book with references to Charlottesville, but the progression of bigotry has not stopped. Since Charlottesville, some have said the alt-right has retreated. And it is true that after the book was finished, the symbols of nationalist intolerance within the White House lost their purchase. Steve Bannon quit, and then with the publication of Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury he was excommunicated from the president’s inner circle. Sebastian Gorka finally left the administration, though he remains a public cheerleader. The leaders of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville vowed that they would return, again and again. They haven’t. But the president called African nations “shithole countries,” ended protected status for Haitian and Salvadoran refugees, and provoked a showdown over young, undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children. Paul Nehlen, a Wisconsin businessman from the Tea Party right who has challenged House Speaker Paul Ryan, has openly embraced anti-Semitism as an organizing principle for his campaign. The question of what kind of a country we want is still front and center.

MD: You write with such ease, passion, and energy. Was this a particularly challenging book to write or a project you felt almost a mission to complete?

JW: It was remarkably easy. My first book was a novel, No. 4 Imperial Lane. It took about three years to write. I have another novel that is three-quarters finished and doesn’t seem to be progressing at all. This one just spilled out. I conceived of five chapters, wrote the most rudimentary of outlines, and then filled it in. I guess I just had to get it off my chest. I also wanted it published as soon as possible.

MD: Who do you consider the ideal audience for your book? What are the most important ideas you would like readers to come away with?

JW: This book is pretty tough on American Jews, too many of whom have subverted the interests of our community and the broader nation for the comfort of their present. I make note that the obsession of American Jews with Israel — especially major American Jewish institutions — has atrophied attention on current events in the U.S. There are progressive Jewish institutions, conservative Jewish institutions, and moderate Jewish institutions, and they all argue over Israel. This obsession blinded American Jewry to the rise of the alt-right. So I would say the ideal audience is the complacent Jew who has not reflected on the Jewish community’s place in America and the importance of democratic pluralism to the security of Judaism itself. But I do not want the audience to be — nor do I think they will be — solely Jewish. All Americans should be vigilant about the erosion of democratic institutions and the rise of intolerance. That is what I hope readers will take away from the book.

MD: If you could require the president to read one book in addition to your own, what would it be?

JW: The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, but if that is too challenging, Timothy Snyder’s brief, eloquent On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century will do.

MD: Toward the end of the book you say that institutions matter, they need to be defended, and they do not survive on their own. Do you, like Timothy Snyder and other scholars, fear that we may be sliding toward an American authoritarianism?

JW: That is my biggest fear, yes. I would never wish economic hard times on this country, but the strong economy, low unemployment, surging stock market and new tax cuts have made me far more worried that voters will overlook the affronts to our Constitution and democratic principles and decide against a change of course. Short-term economic gain is a powerful anesthetic.

MD: Are you sanguine or worried about whether we have the adequate institutional and constitutional protections to prevent this?

JW: As I wrote in the book, Americans do not seem to be marching as sheep into some authoritarian future. The public sphere crackles with dissent. There is joy in rebellion. We do believe in our institutions, and thus far, the courts appear to be maintaining their independence and the free press is reveling in its freedom. That said, Congress — the first branch of Constitutional democracy — has been remarkably docile. Oversight is almost nonexistent. Even Democrats have been unable to articulate a principled stand for pluralistic democracy, worried that any elevation in rhetoric could drown out the search for lunch-pail issues that could win back white working class voters who drifted to Trump. It really is up to the American people to stand firm. Their representatives in Washington won’t.