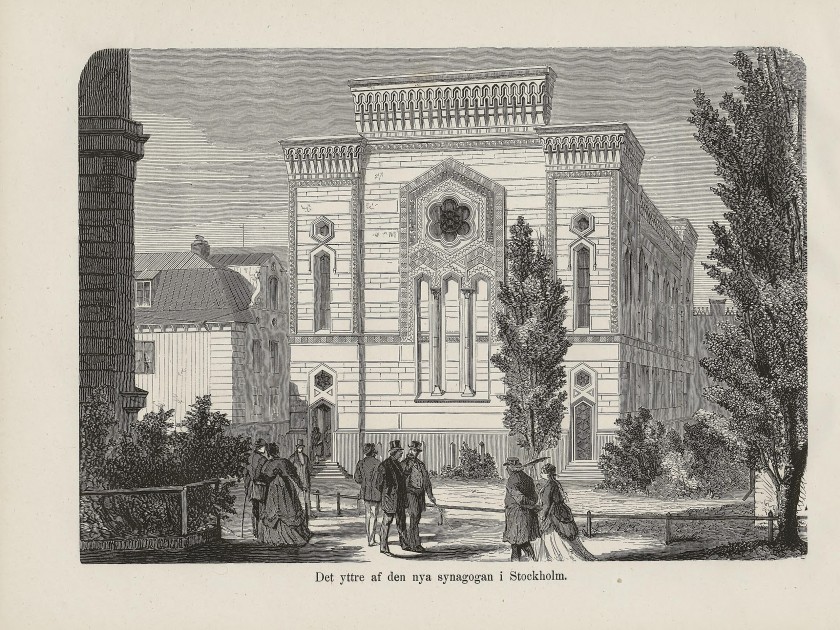

The exterior of the new synagogue in Stockholm, National Library of Norway, 1873

Stockholm’s Old Town is maze-like and is easy to get lost in. But since it is located on an island, sooner or later you will return to a familiar spot and realise that you have walked in circles.

There are two small triangular city blocks that look very similar. Stockholm’s Jewish museum is located in one of these areas today. Centuries ago, this is where Sweden’s first synagogue was located.

In my novel Dr. B., the protagonist — based on my grandfather, Immanuel — visits the German church, located in the Old Town. In the dimly lit church he spots a hardy little boy who turns out to be the bell ringer. After a dream-like experience in the church’s tower, watching the boy execute his duties, and a puzzling conversation with a Lutheran priest, the protagonist gets lost in the labyrinth of narrow streets. He keeps returning to that square where the synagogue once was located.

The boy, the son of a Jewish librarian, remains an elusive and mysterious figure throughout the novel. His performance in the tower is otherworldly: “The bell ringer’s dance was terrifying but also beautiful. It was like nothing he had ever seen before and difficult to describe in a way that did it justice.”

Dr. B. was the byline used by my grandfather, a journalist who escaped the Nazis in 1939 and settled in neutral Sweden with his wife and two sons. He was an assimilated Jew, the son of a well-known cantor in the synagogue in Königsberg. My novel is not really a portrait of him, even if it is called Dr. B.; the book is better described as a portrait of a city — Stockholm, 1939. It’s a story full of shadows, reflections, and ambiguities. My protagonist is exhausted and so perhaps he sees things that no one else can.

For instance, does that bell ringer really exist? Or is he a figment of Immanuel’s imagination? He follows him through the winding streets and in the end, Immanuel remains uncertain if he is really there:

“The streets were empty, but he glimpsed an unsteady figure a stone’s throw ahead of him, keeping close to the buildings and then disappearing around a corner. He turned the corner too and thought he could see the short figure again, casting a long shadow on the wall opposite. The light must have come from a low window, but to his surprise all was in darkness when he reached that part of the street. He wasn’t sure he was going in the right direction, and again he was filled with a sense of disquiet. The feeling intensified at the thought that he had recognized the outline of the figure that was walking in front of him a moment ago and was now no longer to be seen. It must surely be none other than the small boy from the tower, the bell ringer. Or was he chasing his own shadow?”

My book is based on real events. I inherited a box full of documents that belonged to my grandfather Immanuel. A few years ago I started to study them and lost myself in letters, articles, verdicts, and interrogation reports. I began to see the outline of a story that was anything but straightforward. There were many things I did not know; for instance, my grandfather was given work as an editor for a leading publishing house, Gottfried Bermann Fischer; they were a German Jewish publisher who moved their publishing house to Stockholm in the late 1930s. During the war years, the company published many of the most significant writers banned by the National Socialists, including Thomas Mann and Stefan Zweig.

Zweig’s last and best-known book, The Royal Game, was published in Stockholm after the author’s death. The last thing Zweig did before taking his own life was to send the manuscript to Bermann Fischer. The main character in the story is imprisoned; in his isolation, he studies a book about famous chess games, thereby developing miraculous skills as a player. He plays chess with himself, splitting himself into two.

My grandfather worked for Bermann Fischer in Stockholm in 1939 but was caught up in a complicated spy intrigue. He was supporting British Secret Service agents but was arrested and sentenced to eight months’ imprisonment for spying for the Germans. The publisher Bermann Fischer was also arrested; he was deported from Sweden and with his family managed to make the journey to New York via Russia, Japan, and California.

Fischer met Zweig in New York just before he undertook his last journey, perhaps before writing The Royal Game. Did the publisher tell him about the new editor, the one who ended up in prison and made sure the publisher himself was forced to experience a number of weeks locked up? The name of the chess-playing prisoner in Zweig’s novella convinces me he did: that name is Dr. B.

Am I claiming that Zweig’s protagonist is modelled on my grandfather? Not really. Like most fictional characters Zweig’s chess virtuoso is a collage. Inspiration must have come from many sources. Instead of a psychological portrait, I have constructed a narrative in which the dual nature of Zweig’s chess player — the doppelgänger motif — becomes a structural element to reflect a story full of doubles. The book is full of symmetries and mirror effects. The inner tensions of the assimilated Jew have moved outside: he is torn between irreconcilable extremes. From the Lutheran church in the Old Town he is constantly pulled back to the site of the ancient synagogue. The strange Jewish boy in the Church keeps returning but perhaps exists only as Immanuel’s shadow.

Philosopher and art critic Daniel Birnbaum is one of the world’s most prominent art curators. He is the former director of the Moderna Museet (Museum of Modern Art) in Stockholm and has managed museums and art schools in Germany and Italy, and curated the Venice Biennale. He is currently the artistic director of Acute Art, an avant-garde studio based in London, and a contributing editor at Artforum. Dr. B. is his first novel. He lives in London.