Austin Ratner, 2011 Sami Rohr Prize Winner and author of The Jump Artist, shares his remarks from the 2011 Sami Rohr Priza Gala.

82 years ago Philippe Halsman wrote a letter to his girlfriend Ruth Romer from his prison cell in Innsbruck, Austria.

He wrote: “Tell me Ruth have you ever dreamt you were flying?”

And I want to say a few words about flying.

***

Everyone dreams of flying, at least occasionally, don’t they? I had a recurrent dream as a child that by assuming a certain position, I could sneak my feet off the ground without resting my hands anywhere, achieving levitation as it were by catching gravity unawares.

Such a dream is a concrete expression of a wish –the wish to defy the inexorable laws of the universe, such as gravity, which claims the dead as they fall and holds them to the earth, never to rise again.

The wish to rise up, and its predicate – a sense of vulnerability, and a dread of extinction –these feelings pervade Jewish history and Jewish storytelling.

There is the winged seraph of the Book of Isaiah and other angels aloft with the power of an almighty God.

There is the biblical theme of aliyah, ascent, to the land of Israel as an elusive ideal, a sort of heaven on earth protected by god from murderous enemies, from drought, disease, and famine – a deliverance from death.

Even Superman is Jewish. (He’s also from Cleveland.) In 1932 a Jewish man from Cleveland named Mitchell Siegel died in a robbery of his clothing store. The next year his son Jerry, and a friend Joe Shuster, created the Superman story in an evident attempt to make sense of this tragic event.

Superman himself is an orphan, but without Jerry Siegel and his father’s earthbound vulnerabilities.

*** Philippe Halsman’s life story is almost as paradigmatic. But his story, while as tragic and romantic as Superman’s, is also real.

Philippe Halsman’s life story is almost as paradigmatic. But his story, while as tragic and romantic as Superman’s, is also real.

His father fell, and he arose. The Nazi doctor Karl Meixner photographed his father’s corpse and years later Halsman photographed Judge Learned Hand, at age 87, jumping in the air, floating in the plasma of suspended time that is a photograph.

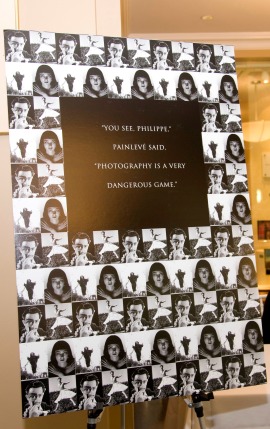

He went to prison and was freed by the French minister of aviation, Paul Painlevé, a former Dreyfusard and one of the first passengers of Wilbur and Orville Wright.

***

The fact is, as of 108 years ago, people can truly fly. Human beings realized that longstanding dream, among many others, through experiment, struggle, error, and persistence.

It isn’t the superheroic flight of levitating at will. It’s flight burdened with the complexities of reality – such as terrifyingly loud toilets and the unlikely event of a water landing – but it’s flight nevertheless, up in the clouds.

The story of the founding of Israel is so compelling because it is an improbable, romantic dream made into a reality, however fraught with complexity that reality may be.

In a smaller way, the Rohr prize echoes that notion of Theodor Herzl’s: “If you will it, it is no dream.”

Writers spell out dreams and visions on the page, of course. Theodor Herzl was a writer – for the same Vienna newspaper in which Sigmund Freud defended Philippe Halsman, one notes – and so was Superman – his day job was as a beat reporter for the Daily Planet. That’s right. Superman was a Jewish writer from Cleveland. And don’t forget it.

And though an artist doesn’t intend his creations to walk the earth, he does hope to create an object of beauty and meaning in the real world – a real world that’s often harsh and indifferent toward its artists.

As the character Lousteau says of the life of a novelist in Balzac’s Lost Illusions:

“You will have ruined your life and your stomach to give life to this creation, and you will be libeled, betrayed, sold, consigned by journalists to the lagoons of oblivion, buried by your best friends.”

“You will have ruined your life and your stomach to give life to this creation, and you will be libeled, betrayed, sold, consigned by journalists to the lagoons of oblivion, buried by your best friends.”

Similarly, Gustave Flaubert remarked during the composition of Madame Bovary:

“I am leading an austere life, stripped of all external pleasure, and am sustained only by a kind of permanent frenzy, which sometimes makes me weep tears of impotence but never abates. I love my work with a love that is frantic and perverted, as an ascetic loves the hair shirt that scratches his belly.”

And the reward for all that sacrifice may be nothing in a society that, according to Flaubert, has the following attitude to great literature:

“It knows that [the classics] exist, would be sorry if they didn’t, realizes that they serve some vague purpose, but makes no use of them and finds them very boring.”

***

For a writer, each story, each book, each submission, is a zeppelin full of hope, many of which are doomed to descend in flames.

This prize not only keeps aloft writers’ hopes, but helps defend a place on earth for the existence of art. Physics doesn’t favor the arts, but the Rohr family does.

I don’t pretend that my fellow nominees are undeserving of this prize, or that I’m the only one who might have won it. I congratulate them whole-heartedly and at the same time I hope they won’t begrudge me the right to celebrate today.

Making this book a reality was for me an existential struggle that seemed at many points as if it would end in despair – with years of my life wasted by labor over a book that nobody cared to read. Yet I persisted.

And after all that, this prize is so redeeming of the struggle. It makes me feel that deep satisfaction of making a good and lofty dream come true in reality, against all odds. It makes me feel myself like Philippe Halsman, the Jump Artist.

Austin Ratner is the author of The Jump Artist. Read more by Austin on the JBC/MJL Author Blog series here and read a mini-essay he wrote on Mark Helprin’s Ellis Island here.

Austin Ratner is author of the novels In the Land of the Living and The Jump Artist, winner of the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature, and the non-fiction book The Psychoanalyst’s Aversion to Proof. He is an M.D., studied at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and he teaches creative writing at the Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop in New York.