When my daughter, now a young adult, was around ten years old, she wrote a letter to the makers of American Girl Dolls asking about the possibility of a Jewish doll. Like the exclusive country clubs of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the sought-after group of dolls was all-Christian (and, until 1993, all-white). She received a prompt and courteous response thanking her for entrusting American Girl to represent her traditions, but informing her that no such doll was on the horizon.

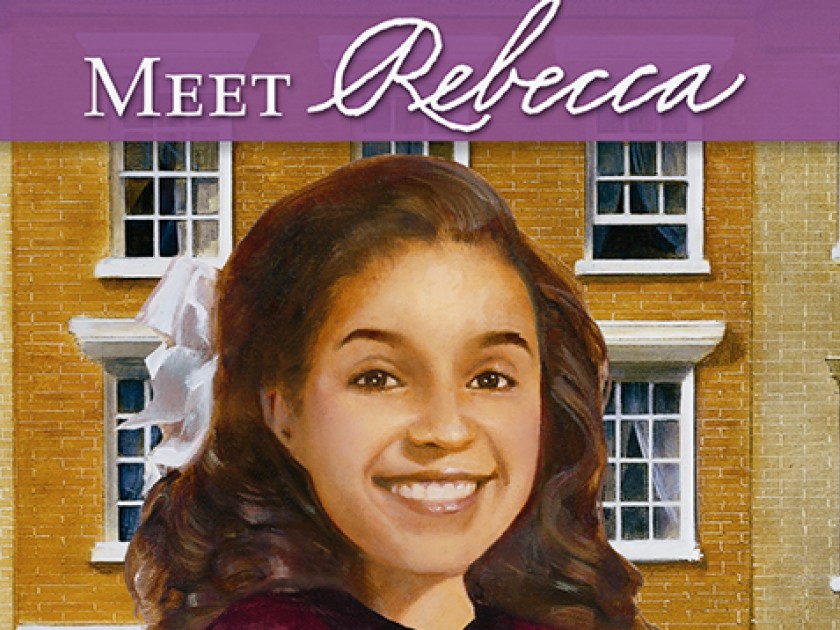

Enough Jewish American girls other than my own must have asked for the same, because in 2009, American Girl introduced Rebecca Rubin, their first Jewish historical doll, to the world. Her debut was announced everywhere from The New York Times to The Jerusalem Post. For standing only eighteen inches tall, she carried a lot of weight on her shoulders. While there have been a number of criticisms leveled at the perceived commercialism of the American Girl enterprise, most Jewish readers had overwhelmingly positive reactions to Rebecca. By adding her to a roster of dolls and stories that trace the history of girlhood in our country, American Girl made a meaningful statement about the significance of Jews in American life.

The original premise of American Girl was to offer a total package of reading and imaginative play rooted in history. To that end, each doll had her own book series. These books have mostly been dismissed by mainstream literary critics as frivolous marketing material simply made to sell more products. While these critiques certainly hold some truth, reading the books now, nearly a decade after their release, it’s evident how much value they still have. The books invite readers to learn about an unfamiliar past, and to empathize with Rebecca as she negotiates family relationships and balances Jewish traditions with the appeal of American life. The Jewishness of these books stands in stark contrast to the Rebecca doll and her accoutrements, which have been increasingly disappointing in their erasure of Rebecca’s Jewish heritage.

With the Rebecca Rubin book series, author Jacqueline Dembar Greene created a Jewish character who celebrated Hanukkah, not Christmas, and who didn’t eat outside of her home during Pesach. Living on New York’s Lower East Side in the early twentieth century, Rebecca was a child of Yiddish-speaking parents. Like any American girl she also loved the new entertainment that movies provided, and enthusiastically sang “You’re a Grand Old Flag” at her school assembly. Showing her belonging in both worlds — religious “old world” and secular “new world” is significant, as Jews in Rebecca’s time were (and to an extent, always have been) suspected of harboring dual loyalties to their people and their country.

While there were many children’s books with Jewish characters well before Rebecca, she was cast into the spotlight in a way that the girls of Sydney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family series, whose profound influence on Dembar Greene is evident, had not been. Rebecca and her books not only needed the approval of Jewish consumers, but also from the wildly loyal fanbase of the whole American Girl enterprise. Rebecca’s story also faced the same skepticism of critics who, quite reasonably, have questioned the literary value of books sold along with dolls priced in the one hundred dollar range. Author Meg Wolitzer was not alone in her dismissal of American Girl’s books, referring to “the seductions of these novels…from the bright paintings…on their covers to the simple plotlines and cheerful if predictable characters.”

Yet, conceding that no one is going to suggest awarding any American Girl book the Newberry Medal, Dembar Greene’s Rebecca Rubin saga is actually thoughtful and sensitive, and immersed in the particulars of Jewish immigrant life of an earlier time. Rebecca may resolve most of her conflicts pretty easily, but at least some of those conflicts are particular to the experience of American Jews.

Like most popular books for young readers, the first Rebecca book poses a central issue to be resolved; in her case, the problem begins with Shabbos candles. If only she had her own pair, perhaps her mother and her condescending older sisters would allow Rebecca to light them. At the same time, this new maturity would possibly convince her parents and grandparents to let her go to the movies. If this best-of-both-worlds combination seems simplistic, Greene at least admits that the Rubins’ secular and religious lives sometimes collide. Rebecca’s father has a small shoe store that he keeps open on Saturdays — a degree of assimilation being the price of success. Working on Saturdays was a common accommodation made by immigrant Jews.

In another chapter, Rebecca confronts a historically typical dilemma for Jewish children in American public schools. Her teacher, Miss Maloney, is utterly obtuse about the problem that her Christmas project poses for the Jewish children in her class. (She also punishes students for inadvertently lapsing into Yiddish.) Overwhelmed with excitement by the prospect of constructing holiday centerpieces out of red candles and genuine Central Park greenery, she is unable to empathize with students who observe Hanukkah, not Christmas. Greene realistically presents a range of responses from the Jewish students. Some claim that their families won’t care, while Rebecca’s friend Rose, formerly Rifka, is anguished at the prospect of bringing home this useless and insulting object. The teacher is patronizing and firm in her refusal to exempt anyone: “Miss Maloney smiled kindly, as if Rose simply didn’t understand. ‘Christmas is a national holiday, children, celebrated by Americans all over the country.’”

Since Rebecca’s debut in 2009, American Girl’s emphasis on the stories of girls from the past has been increasingly sidelined in favor of more accessible, modern dolls. The historical dolls and books have been rebranded as “BeForever,” a phrase that seems pulled from a Disney princess line, and conveys to girls that their lives and those of girls in the past are essentially the same. The books previously ended with a “Looking Back” section that provided historical background; one of the original Rebecca books, for example, had information about the 1909 Shirtwaist strike by primarily Jewish women garment workers. All of the beautiful and detailed color illustrations previously used to bring the stories to life have also been taken out. The newer cover images are a computer-generated horror, with Rebecca looking as if her hair has just been professionally blown out.

But even her original incarnation as a doll showed some reluctance by American Girl to reflect Rebecca’s Jewishness to the degree displayed in the books. The original books, illustrated by Robert Hunt, depict Rebecca with dark brown wavy hair, dark brown eyes, and a prominent nose. The Rebecca doll, however, had lighter hair, hazel eyes, and identical features to the other white dolls.

Rebecca’s accessories have also changed over the years. The company has decided to outfit Rebecca with clothes and furniture that are more Downton Abbey than Hester Street. In Changes for Rebecca, the last book in the original series, our heroine stands up for striking workers, making a powerful speech in Battery Park about “dark, dirty, dangerous” factories, and bosses who would rather exploit people than respect them. But the gaudy, gold-accented bed with hot pink bedding and satin pajamas currently sold along with Rebecca negate the Rubin family’s frugality and fears of poverty that are constantly brought out in the books.

American Girl’s approach to marketing Rebecca’s accessories has also shifted: At first customers could purchase what was called her “Sabbath Set,” which included a miniature plastic challah, candlesticks, and Russian samovar. In 2013, the set was renamed “Rebecca’s Teatime Traditions,” reducing her central religious observance to a light snack — and in contrast to Shabbos candles and other key symbols of Jewish identity playing a central role throughout the book series.

Though still widely available, the original American Girl books are no longer in print. But even if reading about the trials and triumphs of Jewish immigrant life in the early twentieth century comes to seem more distant and exotic, curiosity about the past and questions about its relevance to the present can still immerse children in Rebecca’s stories.

In one scene in Candlelight for Rebecca, Rebecca sits with her grandfather as he reads a copy of the Yiddish Forverts. Rebecca wears a black dress and tights, and a handknit shawl. Troubled by her teacher’s ignorance, Rebecca asks her grandfather if Hanukkah is an unimportant holiday. He folds his paper and gives her his full attention as he explains the meaning of the Maccabees’ revolt, pointing out that immigrants need to learn new ways, but that “we can’t forget who we are, even if it means being a little different.” As a generic message of pride and loyalty to traditions, the grandfather’s conclusion may appeal to any reader. For Jewish readers it has a specific resonance, as unique to Jews as Rebecca’s candles.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.